East is Eden: HSBC – London v Hong Kong

HSBC—one of the two most pivotal banks in the global financial system, according to regulators, alongside JPMorgan Chase—exudes permanence. Its buildings are guarded by lions cast in bronze which passers-by touch for luck. HSBC has never been bailed out, nationalised or bought, a claim no other mega-bank can make. It has not made a yearly loss since its foundation in 1865. While its peers took emergency loans from central banks in the crisis of 2008-10, HSBC, long on cash, supplied liquidity to the financial system.

Yet behind that invincible aura lurks an insecurity: where is home? When Western and Indian merchants founded the bank in Asia in 1865, they considered basing it in Shanghai before settling on Hong Kong. Faced with wars, revolutions and the threat of nationalisation, the bank has chosen or been compelled to move its headquarters, or debated it, in 1941, 1946, 1981, 1986, 1990, 1993, 2008 and 2009.

HSBC believes its itinerancy explains its survival. Countries and regimes come and go. The bank endures. Now it’s decision time again. The results of a ten-month review of its domicile are likely to be announced on February 22nd. The main choice is between staying in London—where HSBC shifted its holding company in 1990-93, in anticipation of the return of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty in 1997—or going back to its place of birth.

The decision is partly about technicalities: tax, regulation and other costs. But it also reflects big themes: London’s status as a financial centre, the dominance of the dollar and Hong Kong’s financial, legal and political autonomy from mainland China, which is supposedly protected until 2047 under the pledge of “one country, two systems”. HSBC’s most recent move, from Hong Kong, was announced on the radio by China’s premier of the day, Li Peng. Its return would be news too, a coup for China when its economic credibility is low. For Britain, the departure of its largest firm would be an embarrassment.

That HSBC is considering moving at this moment may seem astonishing; it is knee-deep in a restructuring. Since taking the helm in 2011 Stuart Gulliver has reversed the empire-building that took place in the 2000s to refocus the bank on financing trade. He has sold 78 businesses and almost halved the bank’s exposure to America. Vast sums have been spent on compliance systems after the bank was fined for money-laundering in Mexico.

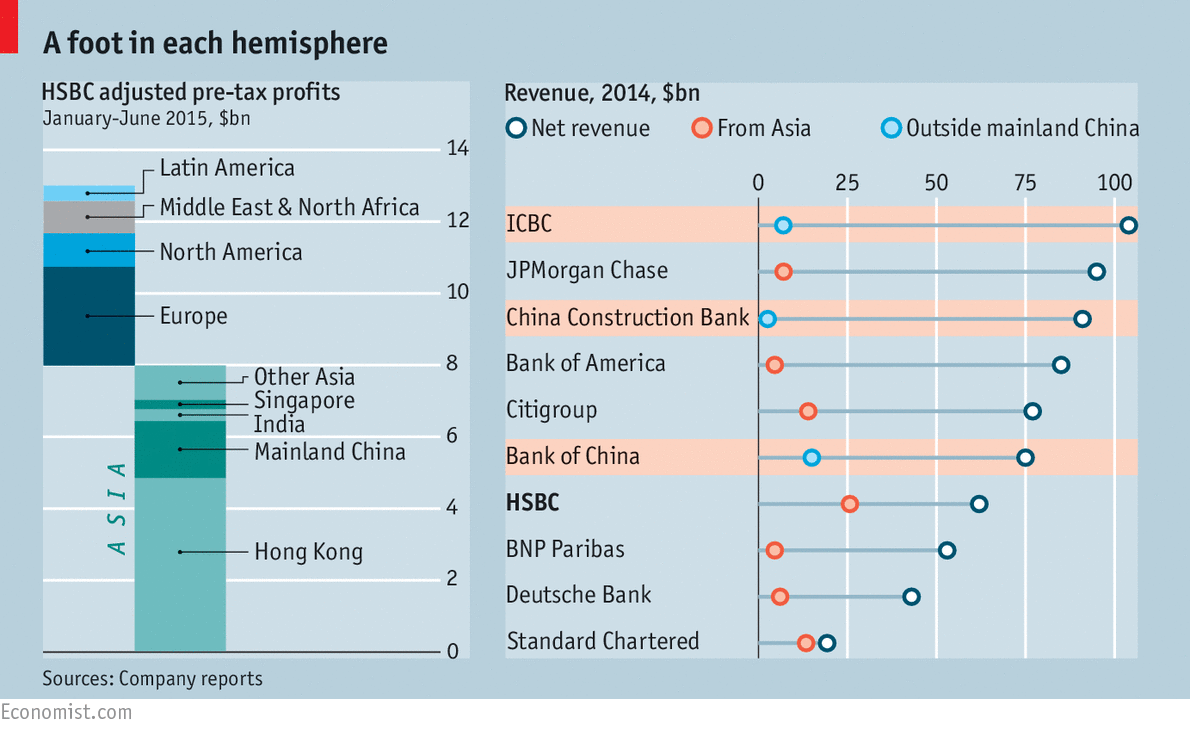

The group’s return on equity hovers at 8-11%—poor by its standards but on a par with JPMorgan Chase. Outside Asia, returns are about 5%. To raise them, Mr Gulliver is inflicting a new dose of austerity, with big cuts at its investment bank. Retreat from the Western hemisphere has freed resources for Asia, where risk-weighted assets have soared by half since 2010.

HSBC’s seesawing skew towards Asia is one of four factors that explain its 151-year quandary over where it should be based. The others are the ethnicity of its managers, Britain’s love-hate relationship with finance and the status of Hong Kong.

In the 1980s all four pointed to London. The bank was diversifying into America and Europe (by 2004 Asia yielded just a third of profits). London felt natural to the cadre of expatriate Brits that ran it. Britain was welcoming, particularly after HSBC bought Midland, a local lender. And HSBC was cushioned from the danger that China would rip up the agreement over Hong Kong. “As night follows day…we would become a Chinese bank,” the bank’s chairman at the time said about keeping its domicile in the territory after 1997.

Three of the four factors now point back towards Asia. Asia yields 60% of profits. This could rise to 75%. Mr Gulliver plans a big push in the Cantonese-speaking Pearl River delta. Rising interest rates would boost lending margins most in Asia, which has a surplus of deposits, which need not be repriced as quickly as debt. HSBC is far more Asian than its Western rivals (see chart). Not even a hard landing in China, a banking crisis there or a devaluation of the yuan would alter that.

HSBC’s management is now multi-national, although its board has too few Asians on it. (Simon Robertson, its deputy chairman, is also a director of The Economist Group.) AIA, an insurance firm, moved to Hong Kong after it was spun out of American International Group in 2010. It shows it is possible to domicile a big finance firm there that is not Chinese-run.

And Britain has got hostile. Briefly after the crisis public and elite opinion distinguished between the British banks that blew up and those that did not. Having a bank so plugged into emerging markets was seen as strategically helpful. But now HSBC (cumulative profits of $101 billion since 2007) is often lumped in with the likes of Royal Bank of Scotland (cumulative losses of $80 billion), a target of attacks from foaming parliamentary committees and a hatchet-wielding media.

Critics worry that British depositors and taxpayers subsidise the bank by funding its foreign operations and implicitly guaranteeing its liabilities. This is the rationale behind Britain’s levy on banks’ global balance-sheets, which costs HSBC $1.5 billion a year, or about a tenth of profits. It also underpins the requirement that banks ring-fence their British retail arms, which will cost HSBC $2 billion.

Yet these policies duplicate others designed to tackle the same problem, including capital surcharges, stress tests, living wills and a push to “bail in” bondholders when disaster strikes. And they ignore HSBC’s safety-first structure. It has more cash than it owes in debt (bonds and loans from other banks). It is already run in self-reliant geographic silos. And 68% of its deposits are raised outside Britain. Arguably the subsidy flows in the other direction, from Asian savers who are providing cheap funds to Britain’s financial system.

George Osborne, Britain’s chancellor, has belatedly turned on the charm. In July he tweaked the levy and the tax regime—although not by enough to make much difference to HSBC over the next five years. The financial watchdog has been shaken up, and Mark Carney, the boss of the Bank of England, which has ultimate responsibility for the banks, has hinted that they have enough capital.

But unless the government concedes that the size of HSBC’s global balance-sheet is not a gauge of its risk to Britain, HSBC will worry that its size is capped. Asia will grow faster than Britain, and thus so will the bank’s assets. If the bank is too big for Britain today, with assets equivalent to 89% of GDP, what will it look like in 2030? A British exit from the European Union would complicate things further, requiring HSBC to beef up operations in France or Germany (although it would have to do this whether based in London or Hong Kong).

What about the fourth factor, Hong Kong? It has changed a lot since Mr Gulliver first lived there in the 1980s. The skyscrapers of China’s opaque lenders, Bank of China and ICBC, now loom over HSBC’s building, beneath which pro-democracy protesters camped during the Occupy Central movement in 2012.

Hong Kong’s government would welcome the bank back, as would its regulator, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA). Moving to Hong Kong would probably cut HSBC’s tax bill and capital requirements a bit and the degree of regulatory and political friction a lot. It might also help HSBC’s ambitions on the mainland, although it already has a privileged spot there—the largest presence of any foreign bank. Like Hong Kong, HSBC wants to be close to China but not integrated with it. Head-to-head competition with the coddled mainland banks would be suicidal.

The logistics of a move would be less daunting than you might think. Half of HSBC’s business already sits in a subsidiary in Hong Kong that the HKMA regulates. HSBC’s shares are listed in Hong Kong as well as London.

But how could the territory safely host a bank nine times as big as its GDP? Hong Kong officials say there are three lines of defence. First, they set more store than Britain on HSBC’s innate strength: its culture, capital and vast pot of surplus cash. Second, they believe that in a crisis its geographical silos would get assistance from the local central bank: the Bank of England would help the British arm, the Federal Reserve the American one, and so on.

Last, there are the HKMA’s foreign reserves of $360 billion. They exist to protect the currency peg with the American dollar and “the stability and integrity” of its financial system. Were HSBC ever to cock up as badly as, say, Citigroup has, it might take $50 billion to re-capitalise it—within Hong Kong’s capacity. A liquidity run so bad that it drained even HSBC’s cash pile could be harder for the HKMA to manage. It runs a currency board so cannot print Hong Kong dollars in unlimited quantities. HSBC largely operates in American dollars, which the HKMA cannot create, and unlike the Bank of England, the HKMA does not have a dollar swap line from the Fed.

Wrinkles like this mean that HSBC would ultimately rely on the unspoken backing of mainland China, with its vast financial resources. Speaking anonymously in August, a mainland official formerly in charge of financial matters said Chinese regulators would expect to have a say over HSBC. China desperately wants a global bank to represent its interests. Mainland officials might be tempted to meddle.

That might annoy American officials, who have become chauvinistic about access to their financial system since the 9/11 attacks and the 2007-08 crisis. HSBC manages about 10% of the world’s cross-border dollar payments. Its ability to do so is essential to the bank’s operations. In the event, say, of a military skirmish between America and China, it is not impossible there would be a backlash from Congress and New York’s populist regulator against a “Chinese” bank having such a privileged role in the dollar system. In 2014 regulators briefly prevented BNP Paribas, a French bank, from clearing dollar transactions.

A move to Hong Kong is thus a risk for HSBC. It is a bet that China will grow, but that its legal and financial systems will remain backward enough that Hong Kong will still have a vital role as the mainland’s first-world entrepot. It is a bet that even as they meddle in Hong Kong’s politics and on occasion break its laws, mainland officials will ultimately respect the principle of “one country, two systems”. It is a gamble that America will resist its worst urges. In Hong Kong HSBC would be a catastrophic mistake away from losing its independence—but then the bank has never made a catastrophic mistake. Viewed from an insular Britain, Hong Kong is dangerous and alluring, just as it was 151 years ago.

Feb. 6, 2016 on The Economist

Read more here