Deep In A Pit

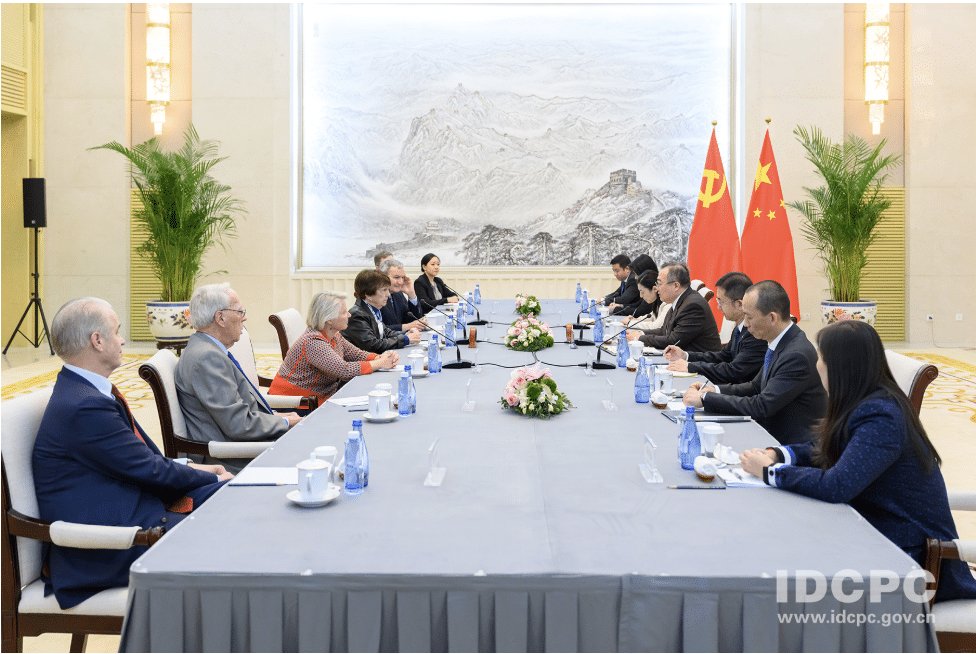

“COMMUNIST Party give us back our money”, “We want to live, we need to eat!” Such were the slogans daubed on banners that were displayed on March 12th during a protest by thousands of coal miners in the dingy streets of Shuangyashan, a city in Heilongjiang province near the border with Russia. The demonstrators gathered outside the headquarters of Longmay, the largest mining company in the north-east and Heilongjiang’s biggest state-owned enterprise (SOE). They demanded wages which they said they had not received for at least two months. Some protesters blocked railway lines; others scuffled with police wearing riot gear. Internet censors deleted pictures of the unrest (such as the one shown) as they spread across social media.

The protest was one of the biggest by workers at an SOE for many years. It was an indication of the problems that China’s government will probably face as it seeks to cut excess capacity among SOEs like Longmay and reduce their enormous losses. In February the labour minister, Yin Weimin, said that 1.3m coal workers and 500,000 steel workers could lose their jobs over the next five years.

Other estimates say 3m-5m people may be thrown out of work in these industries as well as in aluminium production and glassmaking. That is far fewer than the tens of millions who lost their jobs during SOE restructuring in the late 1990s. But the economies of some cities, including Shuangyashan, are driven by a handful of large SOEs. In these, downsizing will be traumatic and possibly turbulent.

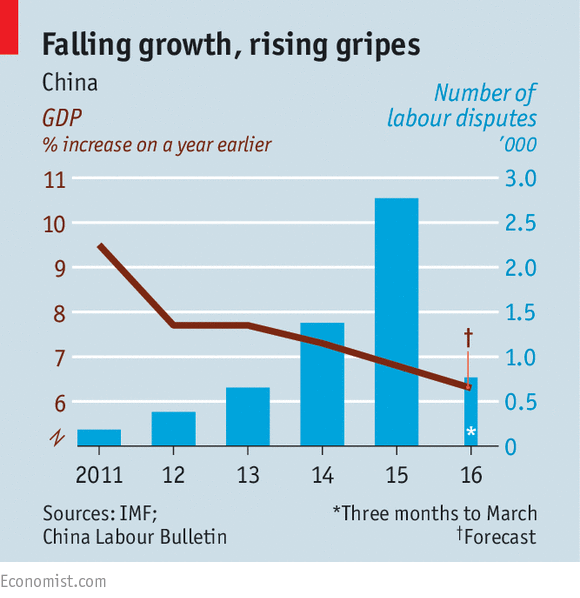

Labour unrest is rising everywhere as economic growth slows (see chart). Many firms, like Longmay, are reacting to financial distress by paying wages late or not at all. According to China Labour Bulletin, a Hong Kong-based NGO, there were 2,700 strikes last year, twice the number in 2014. In the two months leading up to China’s lunar new-year holiday in early February, there were over 1,000 strikes and protests, 90% of them related to the non-payment of wages. Three days after the protest in Shuangyashan, an almost equally large one began at Tonghua Steel in neighbouring Jilin province, also over wage arrears.

In Shuangyashan (its name, meaning Double Duck Mountains, refers to the shape of two nearby peaks), the authorities have tried to soothe the protesters by giving them overdue pay. Some mine workers say they have now begun receiving their salaries for January, and that they have been assured their pay packets for February will be coming soon. But the government remains nervous of further unrest. On March 15th police were still ubiquitous, on the streets of Shuangyashan as well as outside a nearby mine. In the city centre, a row of women who said the men in their families all worked in mines sat holding placards offering their services as cleaners or house painters. “We have no money to eat. What do they expect us to do?” said one woman angrily before being told by police to stop talking. A man who identified himself as a government official followed your correspondent everywhere.

The protests in Shuangyashan were particularly embarrassing for the party, occurring as they did during the 12-day annual session of China’s parliament, the National People’s Congress (NPC), which ended on March 16th. Every year during the NPC session, officials try even more strenuously than usual to prevent street unrest, lest it tarnish the image of political unity and national prosperity that they want the NPC to project (see article). Party bosses in Heilongjiang will get their knuckles rapped by leaders in Beijing for failing to anticipate this outbreak, which followed months of grumbling among Longmay’s workers about lay-offs and overdue pay. In September, the company said it would shed 100,000 of its 240,000 staff.

Remarks made during the NPC by Lu Hao, Heilongjiang’s governor and its deputy party-chief, appeared to ignite the unrest. On March 6th Mr Lu said Longmay’s 80,000 coalface workers had not gone unpaid in any month, nor had they been “shortchanged a single cent”. This prompted outrage in Shuangyashan, where many people said that some miners were owed up to six months’ wages. To avoid heavy punishment, protesters in China normally stop short of attacking senior leaders by name. One of the miners’ banners, however, proclaimed: “Lu Hao talks rubbish with his eyes wide open”.

Mr Lu, who at 48 is China’s youngest provincial governor, had been regarded as a rising star—a possible candidate, even, for elevation to the ruling Politburo next year. He is thought to be a protégé of President Xi Jinping. Whether he will remain a favourite is now in doubt. Global Times, a newspaper in Beijing, called Mr Lu’s performance (without naming him) “regrettable”. Mr Lu said he had been misled. Longmay, he clarified, had not only failed to pay workers, but was also in arrears on its taxes and contributions to social welfare.

Shuangyashan’s problems may be extreme, but they are familiar to many political leaders—not least in the north-east. The region is home to many of the large state-owned firms that have found themselves saddled by vast amounts of spare capacity thanks to a slump in demand. The coal and steel industries are among the worst affected. Output of both fell by 6% in the first two months of the year but demand is falling faster. Total debt in China, at 240% of GDP, is alarmingly high; SOEs have the biggest share of it. Many are not earning enough to service existing debts, so they are borrowing more to pay them off.

Ducking out?

The government appears to recognise that the only way to break the debt cycle is to close or slim down loss-making firms. At the end of the NPC, the prime minister, Li Keqiang, repeated his commitment to “structural reform”, and said the government would strive to find new jobs for those laid off. The labour ministry says it is setting up a fund worth 100 billion yuan ($15 billion) to help redundant workers find new employment. Some Chinese economists worry that this will not be enough and that the government will lose its stamina for tough reform.

The north-east weathered the SOE shake-up of the 1990s with the help of dollops of central-government aid. It is likely to need a lot more. A sign over the exit of a work site near Shuangyashan reads: “The Number Three Mine will have a more beautiful tomorrow!” This week may have been slightly better than the previous one for miners who got their pay, but for many residents the future is hardly alluring.

Mar. 19, 2016 on The Economist

Read more here