An Interview with Ian Johnson: Sparks, China Unofficial Archives, and U.S.-China Relations

- Interviews

Juan Zhang

Juan Zhang- 06/11/2024

- 0

[Editor’s note: Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, author, and researcher Ian Johnson recently published his newest book, Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and Their Battle for the Future. The book challenges the stereotype that the state has quashed all free thought in China, revealing instead a country engaged in one of humanity’s great struggles: the battle of memory against forgetting. Johnson sees it as “a battle that will shape the China that emerges in the mid-21st century”. The U.S.-China Perception Monitor recently interviewed Johnson to discuss the significance of such underground historians, pressing issues in U.S.-China relations, and his latest work, China Unofficial Archives.]

In your latest book, Sparks, you describe a group of people you call “underground historians” in China who document history that is difficult to publish or different from the official versions. How do you define these underground historians and their work? What is the significance of these historians’ work in regards to the country’s future?

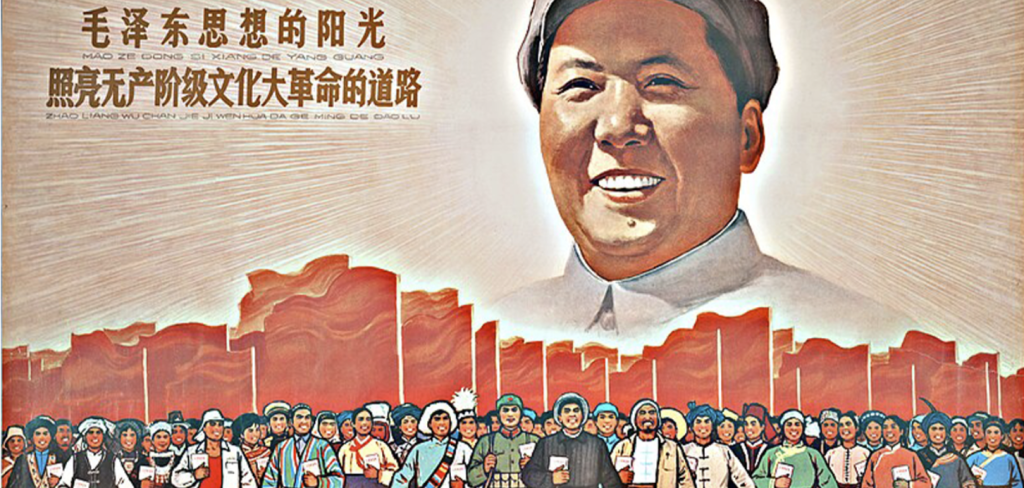

Johnson: One issue is how to define that term “underground.” I was trying to think of a term in English that would be similar to the word minjian (民间) in Chinese, which is something like “popular,” “folk,” or “nongovernmental.” Essentially, underground historians are people who challenge the CCP’s monopoly on history through various mediums, such as documentary films, books, blogs, and even artwork. They don’t necessarily have PhDs in history, though some do.

The term “underground” highlights the asymmetrical relationship between these historians and the government. They are a minority and currently under significant pressure. Interestingly, my book is being translated and published in Taiwan, where they referred to it as “中国地下历史学家”, reflecting the dangwai (党外) movement in Taiwan, which challenged the KMT in the 1970s and 80s. This movement also published books and made movies, and they were referred to as “underground” or 地下. I was thinking that they would use the Chinese term民间but the translators insisted on the term “underground” due to its local significance.

This movement is not about overthrowing the CCP. It consists of a small group of people aiming to preserve historical material for future generations in China. They are aware they won’t be featured on Chinese television, or appear in other mainstream media. Many of these historians had once documented more freely, but now they’re focused on preserving documents and materials. They strive to keep the flame alive until a future time when their work can be more openly appreciated.

You recently launched a website called China Unofficial Archives. What kind of content is published on this website? What is your vision for the site?

Johnson: Initially, people were always asking me—before the book was published—where they could see and get this material. I would say that some of it could be found on YouTube, like movies and other things. But I realized that unless you had access to a major research library, it was very hard to find this material.

My target audience is Chinese people. I knew the site would be blocked in China immediately because of its nature, but many of the people I interviewed and those active in this field use VPNs. My goal was to provide a resource for people mainly inside China without necessarily endorsing all the material. We believe in its value, but we don’t claim every book is good. It’s like a library in that sense. We provide a small description, maybe 500 words, in both English and Chinese.

It’s a bilingual site because English is the international language of scholars, and Chinese is necessary for the texts and movies. I imagined someone interested in a topic could then find more material on that subject. They might discover that others have worked on the same topic or find more films by Ai Xiaoming, for example.

Right now, it uses simple tags. For instance, if it’s related to a specific campaign, for example the Anti-Rightist Campaign, it’s tagged to that campaign. We also tag based on era, format, and creator, by which we mean authors and directors. So you can simply search for all the works we have on an author. Or you can cross search and find all the films we have on the Cultural Revolution. We are in the process of upgrading to a new database software to make the entire texts searchable, maybe not the movies yet, but the texts, to find words and terms. We’re also adding mapping functions and other features. We’re still in the early stages. We launched the site knowing it wasn’t perfect, but we wanted to get it out there, let people use it, and gather feedback.

An article in the New York Times recently said that the newest phase of U.S.-China trade tariffs represents the end of an era for cheap Chinese goods. Is this simply a short-term campaign tactic for President Biden or a long-term U.S. trade policy?

Johnson: In terms of cheap Chinese goods, I think it’s already ending because China is moving up the production ladder. They’re no longer just producing basic products, so this shift was inevitable. However, when I consider the administration’s policy, it seems to be evolving into a form of industrial policy that may not benefit U.S. manufacturers, let alone consumers, in the long run. I understand the need to protect ourselves from selling our highly advanced technology to China. This makes sense. For example, there’s no need to sell the most advanced chips and similar products to China. But if we continue to designate everything as a strategic industry, such as EVs, I doubt this approach will be successful. It also undermines the global trading system, which the United States used to champion.

Taiwan’s President Lai Ching-te has just taken office, and China conducted a military exercise to deter “Taiwan independence.” Coupled with the strengthened alliances between the U.S. and Japan, and the U.S. and the Philippines, the surrounding East Asian region feels increasingly unstable. What are your thoughts on this issue?

Johnson: I think China is getting more impatient because they want something to happen, but I don’t think they have a very good idea of what to do. They’re not satisfied with the election outcome. I think these exercises were very predictable in that regard—they felt they had to do something to show they don’t like it. But this shows they don’t have a clear policy regarding Taiwan. Conducting these exercises doesn’t make people less likely to support the DPP in Taiwan. On the contrary, it shows that any idea of working closely with China seems more and more discredited rather than credible. I don’t think these policies have a clear direction, but it is clear that China is not happy with the outcome of the election.

There are reports saying the number of Americans learning Chinese is decreasing, and programs supporting this goal are historically low. Is this an inevitable result because of tense bilateral relations? What are the reasons for this decline?

Johnson: I think we have to factor in a couple things. One is that there’s a decline across the board in studying foreign languages, except for Japanese and Korean because of the fascination with soft power, such as manga and K-pop. So, there’s an overall decline in foreign language studies. Regarding China, it’s more about issues within the United States. For example, high tuition costs lead students to pursue practical degrees rather than spending time learning a foreign language, which might not result in immediate job prospects. That’s one factor to consider.

But I think the soft power element is significant. Japanese and Korean language studies have increased while Chinese has declined. This indicates a lack of desirability in learning about China, which is unfortunate because it means that people don’t see many positive aspects of China. They just see human rights violations, air pollution, and authoritarianism—all true. But there’s not much of a counter-narrative, which is a pity because China is a fascinating country with hospitable people, amazing culture, and many things to study.

But the problem is that China doesn’t allow soft power to develop organically. Soft power has to be organic; it can’t be government-manufactured. The government’s mistake is to think that simply promoting a positive image will make people love China. You need an engaging story to tell. China does have some engaging stories but doesn’t allow its people the creativity to tell them naturally, which would make them organically interesting to people in other countries.

We’re talking about 18-year-olds. Rational reasons about China being the biggest economy aren’t that compelling. An 18-year-old needs to be inspired by something, and right now, China isn’t providing inspiring stories.

Is there any way to reverse this situation and attract more American students?

Johnson: In the Cold War, we had various projects for learning Russian, but these don’t seem as common nowadays. The government also hinders travel to China by issuing a level three travel warning, which urges people to “reconsider” traveling there. Some universities are not allowed to send their students to countries with such warnings.

But it’s not all about the government. Many academics are hesitant to travel back to China, which sets a bad example for students—if teachers are too timid to go, why should students? Universities need to organize student groups to travel with their teachers, breaking the ice and demonstrating that China is not as intimidating as perceived. In terms of crime, China is safer than the United States, and Chinese people are welcoming. Critics might bring up issues like the case of the two Michaels (two accused spies by the Chinese government), but this is different. We’re talking about undergraduates going for language studies, who are not at risk of arrest.

This requires more effort, but America is very inward-looking and less engaged with the outside world. There’s also a reliance on technology, like AI, with the assumption that we can use programs to read foreign languages. However, I believe this is a mistake. It will result in a generation that has never been to China, which is a significant loss and even dangerous. Even if China is our greatest rival, we need to understand it better, not less.

During the past several months, we have seen that China has taken steps to attract foreigners to visit the country, including visa applications and credit card use. President Xi Jinping said he welcomed 50,000 American students to study in China. What is your opinion on China’s recent actions in this area?

Johnson: All of those things are fine. It has never been, or even come close to, 50,000, in terms of American students studying in China, including summer class students and short-term visitors. So, 50,000 students is impossible for me to believe at this point. But, again, the problem isn’t so much China. There are technical issues, such as the widespread use of Chinese-specific apps to hail taxis or pay for services, or expensive airplane tickets. But those are short-term issues. The longer-term problems are much more significant.

What are the longer-term problems?

Johnson: It goes back to America. It’s more of a domestic issue: people are just not outward-looking. Everyone is focused on the immediate need for a job right after college. They’re burdened by high debt, so they feel the need to get a job right away. So, yes, university students learning Chinese or some other foreign language would be interesting. But now, it’s seen as a very expensive stepping-stone to a job.

You were a correspondent in China for many years. Looking back, is there anything that you miss about that experience?

Johnson: I liked living in China. I spent about 20 years of my life there, and I still have a lot of friends there. I’m working on some projects and would like to go back, talk to people, and stay in touch. Being in China during the 80s, 90s, and 2000s was a golden opportunity. Maybe I’ll go back in the future as a tourist. However, I don’t intend to return as a correspondent; I think that chapter of my life is over. It’s something better suited for younger people anyway.

You have conducted extensive research on religious issues in China over the years. In 2021, President Xi Jinping delivered an important speech on religion, in which he called on China to adhere to the direction of the Sinicization of religion and actively guide religions to adapt to a socialist society. Since then, what have you observed in China’s religious fields?

Johnson: Sinicization or indigenization in this context means controlling it more closely. I spent a lot of time researching China’s indigenous religion, Daoism, and it’s puzzling how one can call for sinicizing something that is inherently Chinese. What they mean is clearly closer control, and this applies to all religions.

They also use this term to seem evenhanded—to appear as though they are treating all religions equally. In fact, the real targets are Christianity and Islam. These two religions concern the government the most because, despite their long history in China, they are seen as foreign and having strong foreign ties. This is what concerns the government. Islam has been in China for 1300 years, and you can definitely say it has been indigenized. However, being Muslim also involves being part of the global congregation of believers. Part of a Muslim’s duty is to go on a Hajj, an overseas pilgrimage, and many Muslims also attend madrasahs in other parts of the Muslim world, such as Malaysia. There’s nothing wrong with that, but from the government’s perspective, they want tighter control over all faith groups and to discourage any foreign ties.

Christianity is divided into Protestantism and Catholicism in China. The government’s efforts to control Catholicism have led to deals with the Vatican to bring underground Catholic churches under the patriotic church. With Protestantism, it’s more complicated because there’s no hierarchical structure to negotiate with. They’ve closed big urban churches, such as the Early Rain church run by Pastor Wang Yi and the Zion Church in Beijing, to essentially destroy any civil society elements within these religions. They don’t want independent sources of power outside of government control. This makes their approach to religion similar to their approach toward NGOs. Religion is just another area they seek to control.

The crackdown we read about in Western media is focused on these religions. However, Buddhism, Daoism, and folk beliefs, although more tightly controlled than in the past, have more preferential policies. The government is more comfortable with them. Folk beliefs, which include practices like ancestor worship and visiting holy mountains, are not official religions in China, but they encompass a broad array of beliefs and practices. These practices used to be considered superstitions (mixin 迷信) but are now redefined as intangible cultural heritage (feiyi, 非遗). This shift allows the government to support pilgrimages and similar activities that are actually religious but which they can call cultural practices. They prefer people to believe in so-called indigenous religions rather than foreign ones, though they still want these beliefs to be led by the Communist Party.

(Kay Zou contributed to this interview.)

Author

-

Juan Zhang is a senior writer for the U.S.-China Perception Monitor and managing editor for 中美印象 (The Monitor’s Chinese language publication).