Using the Pipa to Bridge Two Cultures: An Interview with Wu Man

- Interviews

Juan Zhang

Juan Zhang- 12/05/2024

- 0

Over 30 years ago, Wu Man, hailing from the shores of West Lake, began her journey on the American and global music stages with just a pipa in hand. Years later, she has been nominated seven times for the Grammy Awards in categories like “Best Instrumental Solo Performance” and “Best World Music Album.” In 2023, she was honored with the National Heritage Fellowship, the highest award in the folk and traditional arts by the National Endowment for the Arts in the United States. She has performed at the White House, graced iconic American venues like the Kennedy Center and Carnegie Hall, and toured China as a specially invited musician with the world-renowned Philadelphia Orchestra. With her small pipa, she has carved out her own space in America.

Often calling herself a “cultural bridge” between China and the U.S., how does Wu Man view the current tense relations between the two nations? Has the chill in relations affected musical exchanges between the two countries? How does she use her pipa to promote cultural dialogue, understanding, and trust? And what advice does she have for young Chinese students aspiring to study in the U.S. amid challenging circumstances? Recently, the US-China Perception Monitor interviewed Wu Man to explore how cultural exchanges, including musical ones, can enhance understanding and communication between the two peoples under the current strained relations.

Juan Zhang: Could you briefly introduce the pipa? What’s your favorite characteristic of it?

Wu Man: The pipa is part of the global family of plucked string instruments and is found all over the world. These instruments produce sound by plucking the strings with the fingers, much like the guitar, the American banjo, the Middle Eastern oud, and the Central Asian dutar. All these instruments share a common origin.

Thus, when introducing the pipa, it’s inaccurate to describe it as purely of Chinese lineage. In fact, I believe no instrument has a “pure lineage”; they all come from different regions, traveling to various corners of the world and undergoing unique evolutions.

The pipa was originally brought to China from Persia via the Silk Road. Back then, it was an ancient Persian plucked instrument called the barbat. When it arrived in China during the Tang Dynasty, it evolved into a traditional Chinese instrument, particularly among the Han people. The pipa has a history of over 2,000 years since it first arrived in the central plains of China, undergoing a long transformation process. From Dunhuang murals and other historical records, we can see that early versions of the pipa were held horizontally.

What I love most about the pipa is its rich expressiveness: it can be incredibly gentle, embodying the refined and serene culture of southern China, or it can vividly depict battles and mimic the rough, powerful tones of percussion instruments. Representative works of the former include Spring River in the Flower Moon Night, while Ambush from Ten Sides exemplifies the latter. To me, the pipa’s versatility allows it to express a wide range of emotions—from tenderness to strength. At its core, it’s a robust instrument. In my eyes, the pipa is deeply humanistic; it’s not just an object but a living, soulful entity. I am particularly fond of this characteristic.

JZ: You started learning the pipa at a very young age. Over the years, what impact has it had on your life?

WM: The pipa is a part of my life because I’ve had a special connection with it since childhood. To me, it has given my life meaning. The pipa is an ancient instrument with a long history. The fact that it has survived today attests to its value. For me, having the opportunity to travel the world with the pipa and preserve this instrument has allowed me to realize my life’s purpose and live meaningfully. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have become a scientist or pursued another field. The one thing I can do is to express my life’s value through this instrument.

Everyone has unique talents. God gave me the pipa as my “livelihood” and bestowed this talent upon me. It’s a relationship of both love and hate for me.

JZ: What do you mean by a relationship of “hate” with the pipa?

WM: The “hate” comes from the immense effort it demands. Making music isn’t as joyful as people might imagine. Once music becomes your career, you must dedicate all your talent and energy to it, which is exhausting. You can ask any musician—they’ll all say it’s not easy.

From a young age, you need to invest significant time into mastering the instrument and honing your craft. Once you reach a certain level, you need to use music to express your emotions, communicate your thoughts, and touch others. This is no easy task.

For me, the “hate” lies in the pressure the pipa brings. For example, last Christmas, my family went on vacation to Europe, but I stayed behind to prepare for a concert. I’ve had to give up a lot—such as my dreams of chatting with friends over tea, hiking, or just having a leisurely time.

That said, the joy that music and the pipa bring is an internal happiness. Collaborating with like-minded musicians and sharing a unique sensitivity in our work is an unparalleled pleasure.

JZ: You mentioned the pipa’s history. While it has a global side to it, most people still see it as a traditional Chinese instrument. What kind of reactions have you observed from American audiences during your performances over the years?

WM: Musical instruments generally fall into a few broad categories: plucked instruments like the pipa, bowed instruments like the violin, percussion instruments like the tambourine, and wind instruments of various types. These categories are universal, and you can find corresponding instruments worldwide.

For American audiences, when I play the pipa, they often find similarities with instruments they recognize.

Just yesterday, I returned from a performance in San Antonio, Texas. An audience told me she could hear tones resembling those of the mandolin, guitar, ukulele, and banjo. I explained to her that the pipa is a highly versatile instrument, and listeners often discover familiar sounds that resonate with them.

JZ: You are a founding member and principal musician of the Silk Road Ensemble. After so many years, as a key member of the ensemble, what insights have you gained about spreading cultures and fostering understanding? Has the ensemble achieved its original mission?

WM: The ensemble was founded in 2000 as a project initially intended to last just a few years. Its goal was to remind people that Eastern and Western music are not isolated or disconnected; rather, they are constantly interacting and interconnected.

For instance, Japan’s biwa is also derived from Central Asia. Many of Tchaikovsky’s compositions were inspired by folk songs, which are often passed down and shared across borders, making it hard to trace their origins. Yo-Yo Ma has noted that much of the material used to craft his cello comes from Africa, not just Italy. Similarly, the pipa, while not originally Chinese, became a Chinese instrument after being introduced to the country.

Our initial vision was to use music to break down unfamiliarity between nations, helping audiences better understand different musical styles, cultures, and instruments. After 9/11, many musicians in the ensemble came from Central Asian countries, making us acutely aware of the project’s importance. We realized the ensemble’s significance extended beyond music—it had a deeper purpose that needed to continue.

On a personal level, my greatest takeaway is that music fosters understanding and mutual respect more effectively than politics. Music is the most direct form of communication and represents human ingenuity. Through music, we hope to remind everyone that humanity shares one great tree, with diverse branches but a common root. Our interconnectedness far outweighs our differences.

Recently, I worked with a European ensemble that included musicians from India, Syria, Tunisia, and Iran. Even though I hadn’t visited many of their countries, our collaboration allowed me to learn about their music, cultures, and customs. It was truly a joyful and harmonious experience.

JZ: Now, U.S.-China relations are at their lowest point in decades, with tensions running high, and educational exchanges have also been affected. Both countries’ media carry a lot of negative news about each other. In your field of musical exchange, have you felt this chill?

WM: It seems that I haven’t felt this chill. A few years ago, my agency and I were indeed concerned about whether my career would be affected by U.S.-China relations since the instrument I play is a traditional Chinese instrument. But now I find that my schedule is even busier than before.

At the beginning of November this year, the Philadelphia Orchestra, one of the top five symphony orchestras in the U.S., celebrated the 51st anniversary of their first friendly visit to China in 1973 with a grand tour supported by both governments. Over two weeks, we toured Beijing, Chengdu, Haikou, and other cities. They invited me to be the featured soloist for the China tour. Being invited to perform in my home country was an incredible honor for me. There were places like Hainan that I had never visited before. We presented Chinese audiences with a world-class Western orchestra and a top-tier Western conductor, while I performed a pipa concerto composed by Zhao Jiping. What I could sense was the Philadelphia Orchestra’s respect and understanding for the Chinese audience and their goodwill towards China. Our performances were sold out in China, and every venue was brimming with a festive atmosphere. From the public’s perspective, we didn’t see a chill; what we saw was warmth.

JZ: In your performance career, how have you personally experienced music as a bridge for U.S.-China relations and as a means of cultural exchange? Can you share one or two examples?

WM: I hope that my work can make the “cultural bridge” between China and the U.S. even stronger. I believe that person-to-person exchanges are very important. Such exchanges can eliminate fear and hostility between people. The hostility between our two countries, I think, largely stems from a lack of understanding and trust in one another. In this regard, an open and tolerant mindset is crucial. When I teach students, I often say that only by learning from different cultures and music can you better understand your own culture, your place, and your unique qualities. Conversely, if others approach my culture with the same mindset, it becomes a mutual process of understanding and building trust. With trust, collaboration becomes much easier. Over the years, I’ve worked with musicians from the U.S. and many other countries, and what I’ve felt is harmony and trust. Relations between countries are essentially the same.

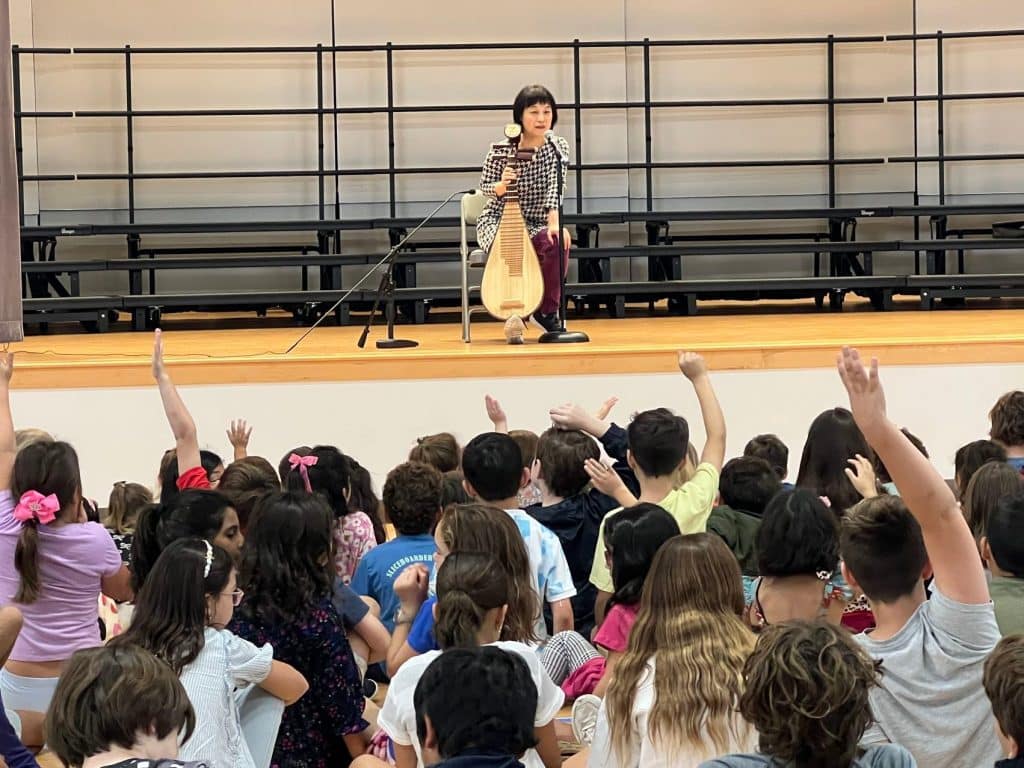

Sometimes, concert organizers schedule guest musicians to visit local elementary schools during the concert season to conduct music workshops. Some musicians don’t particularly enjoy participating in such events, but I find them very meaningful and always agree to do them. During my recent performance in San Antonio, Texas, the organizers arranged a school visit. I went to an elementary school, where the children had already done their homework. When I arrived, they were all excitedly shouting my name, “Wu Man, Wu Man!” I held my pipa and asked them what this instrument was called, and they loudly answered, “Pipa!” Then I asked them where it came from, and they enthusiastically shouted, “China, China!” The atmosphere was lively and joyful. I find such educational activities very meaningful, and I love using this approach to introduce Chinese music to young students. These experiences can stay with them for a lifetime.

JZ: Given the current unfavorable relations between the two countries, many young students are hesitant or unwilling to study in the U.S. Do you have any advice for them?

WM: From my own experiences, I would say this to students: believe in yourself. Have confidence in yourself, and you should pursue what you want. Life is short. If you see your strengths and talents, you should hold onto them.

My hometown is by the beautiful Hangzhou, but at the age of 13, I ventured into the world alone to study in Beijing. When parents let go, children become less fragile and grow stronger.

After graduating from Beijing, I wanted to explore the world. I wanted to see if, as an independent musician, I could build a career on the global stage outside of China. I think my situation back then was much more challenging than what many young people face today. I studied the pipa, which doesn’t have a clear path like math or science, yet I carved out a space for myself.

I want to encourage young people to be strong, steadfast, and confident, and you will surely achieve the life you desire.

Juan Zhang is a senior writer for the U.S.-China Perception Monitor and managing editor for 中美印象 (The Monitor’s Chinese language publication).

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.

Author

-

Juan Zhang is a senior writer for the U.S.-China Perception Monitor and managing editor for 中美印象 (The Monitor’s Chinese language publication).