Myanmar’s Escalating Civil War and the Limits of Chinese Intervention

- Analysis

David Brenner

David Brenner- 12/17/2024

- 0

This article is published in collaboration with Bertelsmann Transformation Index and the BTI Blog.

After more than a year of unprecedented escalation in Myanmar’s civil war, China seeks to intervene in its war-torn neighbor to protect strategic investments. Beijing’s current push to halt rebel advances and force ceasefire negotiations, might facilitate a temporary respite from fighting in parts of the country. But it is unlikely to end or transform a crisis that has plunged Myanmar into humanitarian, political, and economic collapse. And while it first appears as if China is simply throwing its weight behind the embattled junta, the situation is more multifaceted. Geopolitical pressures at least provide leverage to armed opposition movements, not only over the junta but also vis-à-vis Beijing.

From Revolution to War

Myanmar’s current crisis began after General Min Aung Hlaing removed the democratically elected government in a coup in February 2021. Since then, the country has sharply contracted on all political, economic and governance indicators of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI), reversing the progress achieved during the preceding ten years of political transition. Myanmar now ranks 133 out of 137 measured countries of the index. The coup was met by countrywide resistance, known as the Spring Revolution. The military’s attempt to terrorize this movement into submission drove tens of thousands of revolutionaries into taking up arms as part of the People’s Defense Forces (PDFs). Crucial for this mobilization was the support of long-standing ethnonational rebel movements. Known as ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), many of these 20-odd movements have fought for the autonomy and rights of ethnic minorities marginalized by an ethnocratic state for decades. Over the course of this conflict, some EAOs have also built states within the state. As the BTI observes, ‘even before the coup, the state’s monopoly on the use of force was established only in Central Myanmar and in some ethnic community areas.’ The present crisis is nested within this much longer-running armed conflict and has intensified since EAOs started offensive campaigns last year.

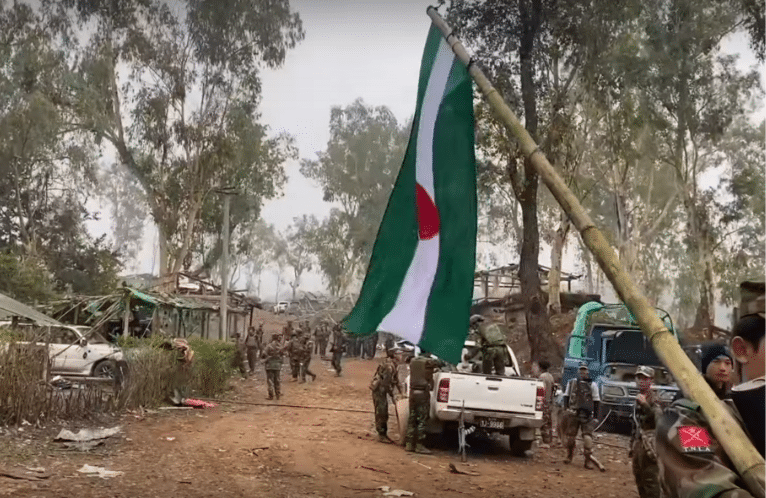

Initially, most EAOs tried to stay neutral in the post-coup crisis between the military and the pro-democracy movement. Their struggle is about the nature of the postcolonial nation-state, not just the political system. The NLD government’s failure to address EAO demands left them disillusioned with the pro-democracy movement. Only a few EAOs, like the Karen, Kachin, Karenni, and Chin, aligned with PDF forces and the National Unity Government (NUG) against the junta in 2021. Since then, the relationship between EAOs, PDFs, and the Spring Revolution has evolved significantly. PDFs have enhanced their capabilities, and EAOs, including non-NUG-aligned ones, have formed strategic ties with PDF forces. By mid-2023, the military odds had changed. In October 2023, the Three Brotherhood Alliance, including the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) and Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) and its allies, captured most of the northern Shan State, including strategic trade routes and urban centers. This push has invigorated armed opposition forces across the country, who have continued to wrestle strategic territory from the junta, including more than 80 towns.

Heavy Weapons and Heavy Minerals

In central and southeastern Myanmar these gains have largely been incremental. TNLA-allied PDF forces cemented their positions around Mandalay, Myanmar’s second-largest city. Karen forces and PDF allies, led by the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), continued to battle the junta along the border to Thailand but also faced setbacks, such as in Myawaddy where the regime managed to hold onto power through a proxy militia. The situation in Myanmar’s central Anyar region is more chaotic as the extreme fragmentation of PDF forces has sparked chaos and fighting between opposition groups. By contrast, western and northern Myanmar has seen a dramatic expansion and consolidation of EAO forces over the past year. Since November 2023, the Arakan Army has conquered northern Rakhine State bordering Bangladesh in ferocious battles involving extreme causalities and, reportedly, war crimes against civilians by all sides. The Rakhine theatre demonstrates how the increasing capture of heavy weaponry in these campaigns has transformed warfare in Myanmar. While armed opposition forces traditionally relied on guerilla operations, the use of heavy weaponry, including artillery and armored vehicles, has added an element of conventional land warfare to current rebel offensives.

This is also the case in the country’s far north, where the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) has expanded its control over strategically located and resource-rich Kachin State, between India and China. This includes border crossings with China, the lucrative jade mines of Hpakant, and Myanmar’s biggest mining sites for rare earth metals, in a region that was previously controlled by a junta-allied militia. Myanmar has quickly emerged as one of the world’s largest sources of heavy rare earth metal elements, the export of which Global Witness estimated to be worth 1.4 billion US-Dollars in 2023. This unregulated and environmentally damaging industry is boosted by the global demand for green energy and is central to China’s economy. It remains to be seen how the KIA will govern these sites, but their capture has increased the pressure on China to involve itself more in the neighboring conflict over whose dynamics it has little actual control.

Increasing Chinese Interventions

Last year China did not oppose rebel advances at its border despite officially supporting the military junta. The Three Brotherhood Alliance has long cultivated ties to China and vowed to protect Chinese interests and targeted a cybercrime complex targeting Chinese citizens. A year later, concerned about its strategic investments like the gas and oil pipeline that circumvents the geostrategic Malacca Strait, China changed tack. It now seeks to halt rebel advances. Beijing reaffirmed diplomatic ties with Naypyidaw, increased arms supplies to the junta, closed border gates to cut rebel supply lines, and negotiated a potential deployment of private military corporations to secure its investments. Chinese officials are currently pressuring the Three Brotherhood Alliance and the KIO to enter ceasefire negotiations with the junta. All four groups have sent high-level delegations to Yunnan in December. In the 1990s and 2000s, ceasefires in this region brought stability, economic benefits to elites of all sides, and some political autonomy but did not address the root causes of conflict. Instead, they allowed for incremental territorialization of the military state apparatus and the rampant exploitation of natural resources. This led to renewed conflict in the 2010s.

The baseline for any negotiations now is different. The military was to arrive from a position of weakness. The TNLA, MNDAA, the AA, and the KIA were to enter from a position of strength. This could lead to more favourable outcomes for EAOs and, thus, be in their interest. Battlefield dynamics do, however, not suggest that the time is right for meaningful negotiations. While top KIA leaders are currently meeting Chinese officials, KIA forces have reportedly started an offensive in Bhamo, Kachin State’s second-largest city. This might be in anticipation of a future ceasefire. But it remains to be seen whether China can exert sufficient pressure to artificially create a mutually hurting stalemate without which a durable settlement is unlikely. Chinese security forces literally kidnapped MNDAA commander Peng Daxun to pressure the group into talks. This approach to forcing negotiations and the collapse of another Chinese-brokered ceasefire earlier this year hardly inspires confidence. Without fundamental concessions from Myanmar’s junta, it therefore seems unlikely that China’s new initiative can create more than a temporary and regionally-limited lull in fighting.

Current talks between EAOs and Chinese officials will therefore go beyond pressuring ceasefire negotiations in aid of the embattled junta. Beijing might be able to blackmail the MNDAA into handing back Lashio, but it cannot reverse the junta’s wider territorial losses of strategic territory. This provides EAOs leverage over China, too. In response to China’s closure of border gates, the KIA, for instance, halted rare earth exports to China last month. Meanwhile, AA forces are closing in on Kyaukphyu, where Beijing invested billions of dollars in a strategic deep seaport in the Bay of Bengal. Research suggests that the AA is not opposed to Chinese megaprojects in Rakhine state. EAO perspectives on Chinese interests have mostly been on the pragmatic side and EAO-China cooperation over economic projects as well as border governance have long been a reality. Part of the talks in Kunming are therefore likely about developing mutual agreements over economic cooperation between China and EAOs. Contrary to some observers who argue that China is now ‘off the fence in Myanmar’, it seems more likely that Beijing continues to hedge its bets in a situation whose dynamics it cannot control.

David Brenner is Associate Professor in Global Insecurities in the Department of International Relations at the University of Sussex. He has researched the armed conflict in Myanmar since 2012 and is author of Rebel Politics: A Political Sociology of Armed Struggle in Myanmar’s Borderlands, published with Cornell University Press in 2019. His recent publications on the topic include Misunderstanding Myanmar through the Lens of Democracy, published with International Affairs in 2024.

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.