Eat More Mapo Tofu w/ Fuchsia Dunlop

- Interviews

Miranda Wilson

Miranda Wilson  Yingyi Tan

Yingyi Tan- 01/20/2025

- 0

As Fuchsia Dunlop said, “pretty much everyone” loves Chinese food. But what is “Chinese food”? Dunlop’s newest book, Invitation to a Banquet, begins with Britain’s beloved sweet-and-sour pork balls, midway through discusses catfish and bear’s paw, and ends with red-braised pork. In total, Invitation to a Banquet, in true banquet style, offers the history of 30 different Chinese dishes. While 30 dishes is only a small portion of the enormous catalog of Chinese cuisine, Dunlop provides a thorough and rich history of Chinese food across China as well as its evolution in the West. As she has said before, Dunlop “eats to understand.”

The Monitor sits down with Dunlop to discuss her interest in China and Chinese food and how this newest book is the culmination of over 30 years of eating and cooking this cuisine. As she notes in the interview, food is potentially the most uncomplicated way the West engages with China. It is apolitical and, of course, delicious. Whether you are a fan of Chinese takeout or a more adventurous eater of Sichuan pepper and 滷大腸 (braised pork intestines), Dunlop shares her insights on how to eat Chinese food — how to appreciate the balance of flavors and textures, recognize the historical significance of each dish, and experience the simple pleasures of eating a good meal.

Invitation to a Banquet will be available for purchase in its paperback edition in the United States on January 21, 2025.

Fuchsia Dunlop is the author of seven critically-acclaimed books about Chinese food: Invitation to a Banquet: The Story of Chinese Food (2023), The Food of Sichuan (2019), Land of Fish and Rice: Recipes from the Culinary Heart of China (2016), Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking (2012), Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper: A Sweet-Sour Memoir of Eating in China (2008), Revolutionary Chinese Cookbook: Recipes from Hunan Province (2006) and Sichuan Cookery (2001, published in the US in 2002 as Land of Plenty: A Treasury of Authentic Sichuan Cooking). Four of her books have been translated into Chinese, including Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper (鱼翅与花椒) and a collection of essays, 寻味东西, both of which are published by the Shanghai Translation Publishing House 上海译文出版社.

Miranda Wilson: What first sparked your interest in China and Chinese cuisine?

Fuchsia Dunlop: I originally became interested in China through an editorial job I had just after leaving university. I was sub-editing a lot of material about the Asia Pacific region, and I decided to go backpacking in China on holiday. That was in 1992, when, as you know, China was a completely different world from the way it is today. It was just beginning to open up. I spent a fascinating month traveling around without speaking any Chinese. When I came home, I started attending a Mandarin evening class, just out of interest. After that, I got a Taiwan summer scholarship for two months of intensive language study in Taipei.

The next year I managed to get a British Council scholarship to study in China for a year. Ever since I was a teenager, I’ve liked the idea of going to live abroad: learning a language, learning another culture. The fact that it was China was something that just happened.

I chose Sichuan University partly because I knew Sichuan had an incredible gastronomic reputation. Ever since I was a child, I’ve really wanted to be a chef. I thought living in Sichuan would be more of an adventure than, say, Beijing or Shanghai, and that I would have more of a chance to become involved in China and get to know Chinese people. I went there in 1994, and it was absolutely fantastic.

There were very few foreigners in Chengdu then. This was before the time when people thought China might be a good career option. Everyone there was interested in various aspects of Chinese culture. While I was there, the food lived up to all my hopes and expectations. The flavors of Sichuan were so exciting, and the food was also incredibly fresh and healthy. I’d grown up in England, where the only Chinese food available tended to be takeaway food, which was very basic and adapted to suit Westerners’ tastes.

I started learning to cook informally in little restaurants around the university, just asking people if I could study in their kitchens. Foreigners were such a novelty at the time that people thought this was a rather intriguing or hilarious idea, and they often said yes. Then I took some private classes at the famous Sichuan Higher Institute of Cuisine.

In 1995, the school invited me to join a chef’s foundation course. I spent three months there in a class of 50 young trainees, with only two women, learning how to cook Sichuan food from scratch. I really did it just for fun, but it ended up changing my life.

Yingyi Tan: It’s so interesting to hear about your first encounters with Sichuan food. Could you share how this book builds on or diverges from your earlier works, such as the memoir Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper published in 2008?

FD: I’ve now written seven books, and five of them have been cookbooks. I wrote my memoir, Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper, because I wanted to tell the story of my own experience as a foreigner learning about Chinese food. I also wanted to try to explore some of the meanings of Chinese food and the stories of the people I’d met in a way that I couldn’t do in cookbooks. That was in 2008. There’ve been more than 10 years since then, in which I’ve continued to travel in China and think a lot about what Chinese food is, what it means in China, and how Westerners have underestimated and misunderstood it.

I’m not just fascinated by cooking but also by the whole culture of food. I wanted to write something that was more in-depth. I think of this book as a guide to how to eat Chinese food with greater appreciation. There’s so much of the culture, the ingredients, the techniques that hasn’t been written about very much in English. Even people who are really interested in food in the West haven’t necessarily thought that much about it. I wanted to offer this as an exploration of what goes into Chinese food – the thinking, the ingredients, the techniques.

It’s very different from a cookbook, but it also builds on the fact that I’m a cook as well as a writer. It comes from 30 years of cooking and eating Chinese food, because, importantly, the eating has been my real education.

YT: Your book was written during the COVID-19 pandemic, did that impact your writing in any way?

FD: It did in the sense that I couldn’t go to China for three and a half years. I started writing the book during the 2020 pandemic summer, although I’d been thinking about it for a long time. The actual process of researching and writing was all done when I couldn’t go to China. It was quite useful to have a bit of distance and perspective to try and draw it all together, and I was also missing China terribly, and missing the friends, the research, and the time I spent there. There’s a sort of love and nostalgia in the book, that comes from that absence and missing people. I feel that I wrote with a lot of affection, and I hope that comes across in the book.

MW: In the West, there’s a tendency to think of “Chinese food” as a homogenous cuisine, even though dishes and cooking styles vary widely throughout different provinces in China. How should Western audiences conceptualize “Chinese food” differently? How has this conceptualization changed in the past few decades as more Chinese restaurants open overseas?

FD: The situation has radically changed since I started doing this 30 years ago: when I started out, the only Chinese food that most Westerners ever came into contact with was Cantonese. People who lived near Chinatowns might have the kind of Cantonese food that Cantonese people would eat themselves. But apart from that, most people were eating a very simplified form of Cantonese takeout food, which was very much designed to accommodate Western tastes. No bones, no shells, no tricky textures. I think that that was what people thought Chinese food was.

In the last 20 years, however, there’s been an explosion of immigration and visiting by people from other parts of China, not just the Cantonese south, where the original immigrants who created Chinese food in the West came from. There are now, in all kinds of places – not just the biggest cities – Chinese restaurants which are designed to satisfy the tastes of a whole new cohort of Chinese people, and they’re less compromising.

Sichuan restaurants, for example, reflect the growing popularity of Sichuan food in mainland China since about the 1990s. These restaurants were opening because Chinese students wanted to eat Sichuan food themselves. The new generation of restaurants offers very authentic Chinese food. Sichuan was perhaps the first and most influential cuisine in the new generation of Chinese restaurants abroad, but we’ve also seen Hunan, Dongbei (Northeastern food), Shanghai, and all these different regional cuisines. What we see in Western cities is still only a fraction of what there actually is in China; but it already shatters the idea that Chinese food is just one style. I think people can really see that.

It is also incredibly useful to think about what Chinese people say about Western food. People in China talk all the time about Western food, and they make generalizations about it. A lot of people haven’t had much Western food, or they’ve only had KFC or something, and they base their ideas about Western food on the misconception that it’s just hamburgers and sandwiches. There’s this terrible stereotype that so many people have said to me over the years, which is that Western food is ‘very simple and very monotonous.’ From the point of view of someone living in America or Europe, that’s ridiculous. How can you talk about Western food as if it’s just one style? It’s worth remembering that because it gives you a little insight into the way we talk about Chinese food.

In my memoir, I wrote this story about one of my classmates at the cooking school. We were chatting during our lunch break one day and he said, “Oh, Fuchsia, I don’t like Western food.” This was Chengdu in 1995, and I wondered how he’d come to this conclusion. So I asked what Western food he had tried. He’d had KFC once, and that had made up his mind. It’s the same for people in the West: many people who are interested in food are far more aware of what Chinese food is and how diverse it is now, but you still get people who think that it’s just sweet and sour pork and egg fried rice.

MW: Invitation to a Banquet includes several vocabulary lists that highlight Mandarin words or phrases relevant to conversations about food. How can we understand the history and cultural impact of food through the Chinese language? Why is it important to understand the dozens of Mandarin words to describe different “mouthfeels,” for example?

FD: I wouldn’t expect all readers to learn this vocabulary, but I think that it shows what the culture considers important. The fact that the Chinese have so many different words for cooking methods and textures is a reflection of the culture, that it takes food and cooking very seriously. Just seeing a list like that, if you think that Chinese food is just stir-frying and maybe steaming, provides an amazing illumination. It’s the same within Europe. The French, who take food very seriously, have this incredible, immense, specialized vocabulary about food and cooking. That is why we in England have borrowed our food vocabulary from them; everything from “chef,” “restaurant,” “mayonnaise”… to different kinds of pastry and sauce. We’ve borrowed it all from the French.

With China, what I wanted to do with these lists was amaze people by how specific the vocabulary is because it’s a reflection of the way people in China think about food. As a student of the Chinese culinary arts, it’s been absolutely fundamental for me to learn the language of the kitchen. I have a quite weird vocabulary for a foreigner in China because I know all these specialist words for different sorts of slicing or cooking methods and different obscure ingredients. The reason I have to learn the language is because we don’t have English equivalents. I can’t really understand, and I certainly can’t take notes, if I don’t know the original Chinese characters because they’re so specific.

YT: As a native Chinese speaker, even I was surprised by the wide range of vocabulary for all these different textures. This book has been translated into Chinese and resonated with other Chinese readers. Many were surprised by the book’s comprehensiveness and learned about many Chinese dishes for the first time. What messages or insights were you hoping to share with them?

FD: I know from experience that people in China find it very interesting that I have a different perspective. The thing about being an outsider is that you see things differently and you have different assumptions. There are all kinds of things that most normal Chinese people don’t really think about, but when you are a foreigner, you may notice them as surprising. For example, the importance of texture. This is something that is a daily reality for so many Chinese people. Whenever Chinese people talk about food, particularly in the Cantonese south, they always talk about the 口感 (kougan), the “mouthfeel,” as well as the flavor. It is simply part of the pleasure of eating. I don’t think that Chinese people are necessarily conscious of the fact that it’s something very notable about their own culture. Why would you notice if you are inside it?

Historically in China, one of the curious aspects of the culture is that people take food so seriously, both as the foundation of good health and also as an immense source of pleasure. And yet, there’s this historical snobbery about the chefs and the artisans who actually produce food. There’s this longstanding division in Chinese culture between the superior gentleman who would write about food and write cookbooks and poems and appreciate food, and the people who were actually doing all the cutting and cooking in the kitchen.

In my own life, people in China are often astonished that someone who’s a graduate of Cambridge University went to a chef school in China. I think things are changing a bit now, but that’s something that people have seen as really radical. I’ve been asked many times if my parents were devastated when I went to cooking school because there’s this idea that going to Cambridge to do something academic is in some way superior to learning the craft of cooking. I don’t agree with that. I think that cooking is an amazing craft, and the chefs and the artisans who prepare food really deserve respect and appreciation as custodians of Chinese culture. I’m someone who is interested in the historical, cultural, and technical aspects of cooking, and I don’t think they should be divided.

When I give talks in China, I often speak to a lot of young people, and I urge them to learn from their parents and grandparents and see that the actual cooking in China is an amazing cultural resource. It’s something that is threatened by all kinds of social changes: people being busier, takeout, convenience. But it’s something that’s worth conserving as culture and as part of national identity.

This is the first book I’ve written that I knew would be translated into Chinese. I knew I was writing for a mixed audience, but at the same time, I didn’t know how Chinese readers would react. There’s one chapter about rice and grains — about a bowl of rice. I thought this might be quite boring for Chinese readers because they know it all already, about the history of rice and things. But actually, several people have said they found it incredibly moving, and that they have eaten their bowl of rice with greater reverence and respect after reading that chapter. So, that was a surprise to me.

MW: You mentioned the connection between Chinese food and medicine. Would you mind expanding on how eating is connected to health in China?

FD: If you think about what makes Chinese food culture Chinese, one thing that is so particular about it is that food and medicine are inseparable. That’s been the case for more than 2,000 years. The idea is that food is the foundation of good health, and good food has to be balanced and healthy. You deal with disease first by looking at your diet. To a certain extent you get that in other cultures, like in England, you are told, “An apple a day, keeps the doctor away,” but in China, it’s very philosophical and complex. It’s completely embedded in the idea of what food is in a very exceptional way.

Chinese people typically talk about food as health and medicine all the time. Elders will tell you what you should be eating if you are slightly ill, if you have spots on your face, or if you are tired. There’s this culture of talking about food and offering advice about what to eat.

It has impressed me that there is this idea that the most delicious food is also balanced and healthy. Quite often in the West, the idea of the perfect feast doesn’t take into consideration health. You think of all this wonderful, fantastic rich food and cheeses and desserts, but I think that a really sophisticated Chinese banquet will include rich dishes, but also light soups and vegetables. The balance between meat and vegetables in a Chinese meal is very important. Also, a Chinese banquet will often finish with fruit. There’s an idea that gastronomy is also about feeling good and not just about the pleasures of the palate. I find that a wonderful aspiration when I’m cooking for people. I want to please their palates and offer them a delicious experience, but I also want them to feel good and not to feel completely stuffed in an unhealthy way afterward.

Chinese dietetics are kind of resistant, perhaps, to scientific inquiry in that they’re very complex. It’s a mixture of empirical lessons and also folklore, and a bit of magic. There’s a tendency in some young Chinese people to see this as being old-fashioned and Western medicine as being more scientific and sophisticated. But I think that as a way of life, Chinese traditional eating offers a way of looking after yourself, which I certainly find very useful as an outsider. I’m not an expert and I’ve never trained or particularly read a lot about Chinese medicine, but I have learned a bit about how to deal with various kinds of indisposition through diet. I find it quite effective. If you have an acute disease, you may need more drastic action like surgery or big drugs. But the idea with Chinese dietetics is that you keep an eye on how you are feeling before you get to that stage and try to notice incipient symptoms and treat them. It’s a very valuable part of Chinese culture, and I hope that young people value it.

YT: You also mentioned that there’s currently a rising popularity of Sichuan cuisine in China. Young people especially favor dishes with spicy and strong flavors. Do you think the emphasis on eating a balanced diet in China is declining?

FD: Yes, I do. So many young people are not cooking as much. They’re certainly not pickling in the way their parents did or engaging in from-scratch cooking. On the one hand, there is fantastic takeaway food and semi-made food available in China, which is very tasty and convenient, but fewer markets and fewer people are cooking. You have a lot of only children who are forced to study all the time, and they’re not learning to cook from their parents. There’s a terrible loss of cooking skills.

An emphasis on sensory excitement and big umami spicy drama is happening at the expense of those lovely gentle dishes, which were the bedrock of everyday Chinese home cooking. You are seeing rises in obesity and diet-related diseases in China as Chinese people turn to more modern industrialized ways of eating. But my hope is that because the food-health culture is so deeply embedded in China’s cultural DNA, if people want to eat healthily, it is all there to be preserved and rediscovered. In my view, Chinese people are in a better position than people in the West to revive traditional ways of eating healthy.

MW: Your book talks about eating habits in both the West and the East that have negative impacts on the environment and sustainability. How can we understand the climate crisis through food and what are some lessons the West can take from China to eat more sustainably (or vice versa)?

FD: With the climate crisis, one thing we know is that we eat too much meat. This is completely unsustainable. If we carry on wanting to eat more and more meat, then the consequences of this are devastating in terms of water use, pollution, and destruction of rainforests because of the need to grow soybeans to feed animals. We are all in the same boat, and the Chinese are quickly catching up with other nations in terms of eating more meat than they did a generation ago. One thing that anyone can do as a meaningful personal commitment to deal with the climate crisis is to eat less meat. Things are moving in that direction, particularly for young people in the West with eating more vegetarian and vegan food. But the great thing about China is that in Chinese cuisine and Chinese culture, there are so many solutions for the problem of how to eat less meat. Until recently, most Chinese people didn’t eat that much meat anyway.

There are so many dishes where meat is used as a flavoring principle rather than the main ingredient. A piece of meat that would feed one American is cut up into small pieces, stir-fried with vegetables, and served with tofu and other vegetables to make a meal for multiple people. Also, there are all these delicious umami soybean foods: fermented black beans, Sichuan chili bean paste, and soy sauce, which give you some of the rich tastes that you get from meat. I find that by using Chinese techniques, I can eat much less meat and still eat fantastically delicious food that satisfies people who are used to eating more meat.

I think one of the problems in the West is that there is this fashion for vegan and vegetarian eating, but the food industry has responded to that by creating lots of highly processed, industrialized things like fake cheese. Whereas in China, you find a whole culture, for example, of tofu, which is minimally processed and is basically in many cases just soybean, water, and something to set the curds, but using things like fermentation or pressing or frying to give it different textures and flavors. These are much healthier, less processed options than the vegan processed foods that relatives of mine who are not eating meat are eating in the West. I find it surprising that there isn’t more interest in traditional Chinese food as meat alternatives.

YT: What do you think about the future of the food landscape in China? Do you think it’s also going to pivot to Western vegan solutions?

FD: The thing that’s interesting about China is that until the ‘90s, meat was rationed, and there’s a whole generation who were desperate to eat meat for decades. Since the ‘90s, there’s been this great enthusiasm for eating loads of meat and fish regardless of any consequences. It’s seen as part of the positive impact of China getting richer and living standards rising. But it is interesting how among more educated, health-conscious people that I know in Chinese cities, some of them are now eating less meat and trying to eat more whole grains. It’s quite early to say — I don’t know how much of an effect that will have, and I think maybe China needs more education about the environmental consequences of eating meat, as do people in the West.

YT: A recurring theme of this book is that food embodies a rich history of cultural diffusion and exchanges. You have also mentioned in interviews that you “eat to understand.” What role do you think food and culinary traditions play in promoting mutual understanding, especially under this increasingly tense geopolitical competition between China and the West?

FD: It’s really important and significant actually. In the West, most people’s first and most intimate encounter with China is through the food. It’s a way in which people are able to experience Chinese culture in a sphere that is not politically contentious. It’s not complicated. And I think that, more or less, everyone really likes Chinese food.

Westerners who go and live in China are completely converted. Pretty much everyone loves the food. It’s a really good way to see something that is very positive and inspiring about Chinese culture, which is full of teachings for outsiders. If you know more about Chinese food, it’s a way of inspiring respect for Chinese culture. We need that at the moment because so much of what’s in the newspapers is about China as a rival and a potential threat. We need to have a more rounded picture of China, which includes things like food.

There are a lot of Chinese people who are people of Chinese heritage born in America or living in America who have faced the brunt of anti-Chinese prejudice during the COVID-19 pandemic, and for who it’s very difficult now in this fraught international situation. So again, food is something that is a very positive shared experience. It’s also a reminder that Chinese culture is not just about China as a nation-state, it’s also the culture of the Chinese diaspora. I would argue it’s part of world culture.

YT: If you could recommend one Chinese dish to best symbolize your vision of the future world, what would it be and why?

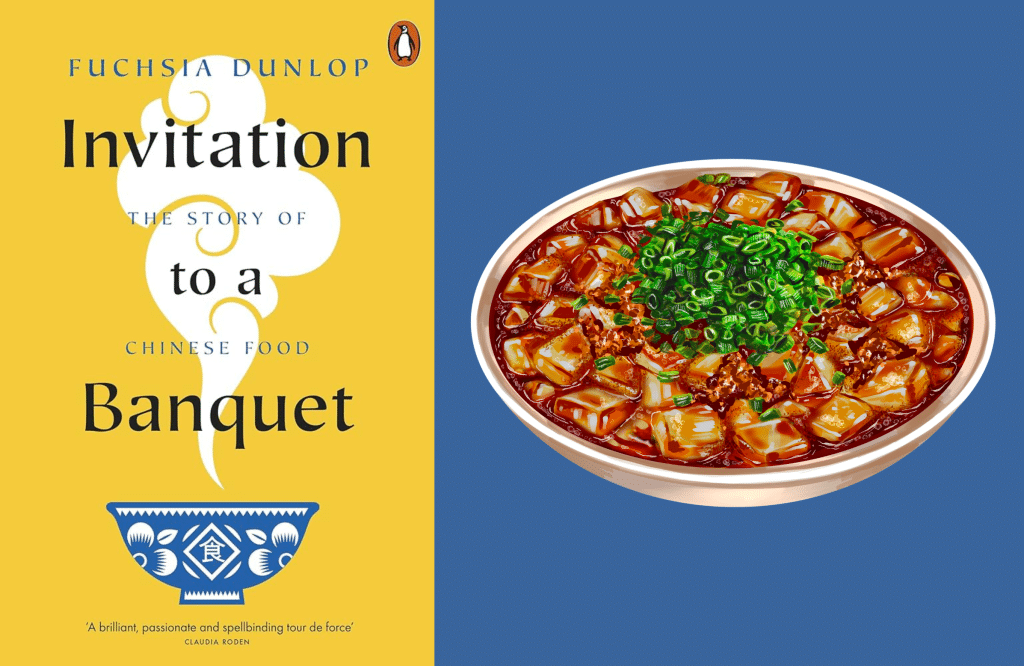

FD: I think it has to be Mapo tofu. The reason is that Mapo tofu embodies that principle of China of a little bit of meat and a lot of vegetables, but with all the excitement and deliciousness of meaty dishes. In that sense, the dish is an invitation to rethink how you handle meat and to eat less of it. For the same reason, it has fermented beans which give that incredible flavor. That’s another option for more sustainable eating. It’s also a reflection of the regionality of Chinese cuisine and the complexity because it’s a Sichuanese dish.

There was a lot of prejudice against tofu in the West because it was seen as being an extreme vegetarian food that no one would eat for pleasure. Mapo tofu shows that doesn’t have to be the case. It’s a dish that is much loved and somehow very much part of Sichuanese identity, which is something that means a lot to me.

Miranda Wilson is a contributing editor for the U.S.-China Perception Monitor.

Yingyi Tan is a Master’s student of International Affairs at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and former intern for China Focus at The Carter Center.

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.