China’s Plans for Greenland & Other Myths

- Analysis

David Fields

David Fields- 02/18/2025

- 0

On 12 February the United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation held a hearing cleverly titled “Nuuk and Cranny: Looking at the Arctic and Greenland’s Geostrategic Importance to U.S. Interests.” American strategic interests in Greenland have not exactly been overlooked recently, or the past six decades. Not by the United States. Not by Denmark. Not by the people of Greenland. The massive island already hosts an American military base (Pituffik Space Base, formerly known as Thule Air Base), many “dual-use” scientific research stations (if these stations were Chinese we would certainly call them “dual-use”), and is a full member of NATO.

But making the case for the strategic importance of Greenland was not exactly the purpose of the meeting as Senator Ted Cruz said in his opening statement:

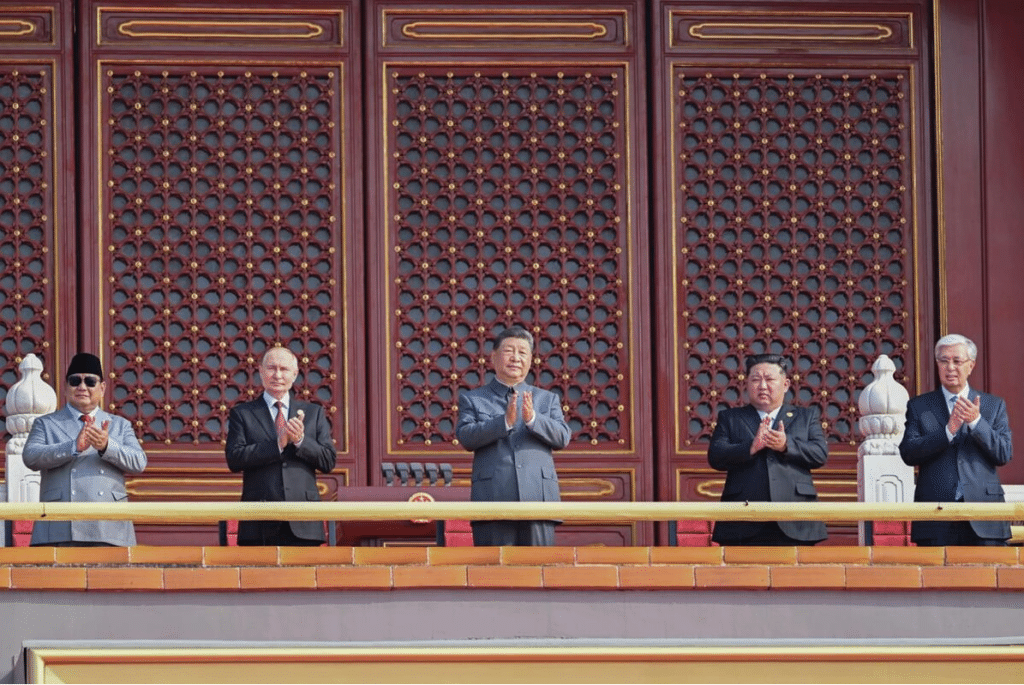

“Acquiring Greenland would have enormous economic benefits for the United States. … The island’s strategic location in the Arctic would provide huge advantages in monitoring growing Russian and Chinese bellicosity in the region.”

Despite the fact that Greenland is not for sale, this meeting was about why and how the United States might acquire it. The “why” had everything to do with China, which was actually mentioned in the hearing more often than Denmark (45 to 41 times)—the country that is not interested in selling the island to the United States.

It appears that China (along with Russia) is a grave threat to Greenland and American interests there. So said former Trump National Security Council staffer Alexander Grey, who explained that China was “preposterously” calling itself a “near Arctic power” and under the guise of what China calls the “Polar Silk Road” is attempting to do in the far north what it is has “long done in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific: undermine sovereignty of developing states at the expense of regional and global security.” In subsequent testimony Gray explained that he had seen this “personally” in the South Pacific, though it happens in many other regions also. He claimed China uses “predatory lending” and “usurious interest rates” to fund “white elephant projects that very often serve no economic purpose” other than to ensnare other countries in “debt trap diplomacy” through which the CCP exercises “coercive political control over small developing states.” Gray went on to explain that Greenland’s future independence from Denmark will leave a vacuum in Greenland, the “100% predictable outcome” of which will be China and Russia filling that vacuum.

If Mr. Gray’s characterization of the Belt and Road Initiative, the Polar Silk Road, and other Chinese investment schemes were true, the threat would indeed be grave. But his characterizations—which were echoed by many senators—are false. It’s as if his knowledge of the topic has not progressed beyond 2018-19, when growth in Chinese lending to Africa did spark fears that China might be attempting to leverage its investments for geo-political gains. These fears sparked investigations, and the investigators came to conclusions: debt trap diplomacy was a myth.

All the way back in 2019, Deborah Brautigam of John’s Hopkins University’s China-Africa Center, explained how this myth—she called it a meme because of the way it spread—moved from an Indian Think-Tank to Harvard to the New York Times to the U.S. Government in record time. After examining case after case of Chinese investment around the globe, and a database of more than 1,000 Chinese loans to Africa she found no examples where the Chinese “deliberately entangled another country in debt” nor used that debt for any strategic advantage. Her cases included the Hambantota International Port in Sri Lanka which is often cited as possibly the only example of debt-trap diplomacy where China has seized an asset as result of non-payment. Except that is not what happened, as Prof. Brautigam shows. The port was put up for sale to pay other Sri Lankan sovereign debts and was bought by a Chinese firm on a 99-year lease. This firm has been operating as any other firm would since that time. This port has not been transformed into a PLA Navy base as some feared.

A 2023 study of Chinese investment abroad by Boston University scholars came up with a much less alarmist and more sensible explanation of China’s investment binge: China had cash on hand and overcapacity in its infrastructure sector. Much of the developing world needed both cash and infrastructure. It was that simple. There is no more strategy (malevolent or benevolent) behind it than that. The findings are so clear, the scholars specifically recommended that U.S. policy makers stop using the term “debt trap diplomacy.” The study also revealed that for better or worse, the heyday of Chinese investment seems to have peaked in 2016 or 2017 and has dropped precipitously since. A 2024 review of jstor.org articles on the topic of Chinese debt trap diplomacy came to the same conclusion: it is a myth.

The Chinese playbook “revealed” by Mr. Gray is an illusion. But even if it was real, how would it play out? How could China actually use investment in infrastructure for geopolitical gain? For Beijing, surely part of the appeal of infrastructure development was an increase in global trade from which it stood to benefit. However, ports, railroads, and roads that could conceivably increase the flow of goods to and from Beijing can just as easily move goods elsewhere if China attempts to manipulate these investments. No one understood this better than Henry Kissinger, which is why he urged the United States to participate in this investment rather than fear it.

The United States should understand the pitfalls of attempting to leverage international investments for geopolitical ends. In the early 20th century, the United States attempted this exact thing under a policy known as Dollar Diplomacy. The policy is considered a dismal failure by everyone who has studied it. Instead of increasing American influence, it dramatically increased American entanglements, especially in Central America where it resulted in dozens of military interventions, the quasi-occupation of Nicaragua for twenty-years, and made the United States the target of several nationalist revolutions. In China, though Dollar Diplomacy was intended to strengthen the Qing government, it actually played a small, but significant role in the collapse of that government, which facilitated greater Japanese penetration into Manchuria.

While the past is no guide to the future, investing for political influence is risky. There is every reason to believe the Chinese government understands this and so have not attempted it. This is likely one of the reasons that Chinese investment remains fairly popular in places where it has been accepted. Besides, why manipulate investments, when just the act of investing increases the public approval rating of China in a country as a 2023 study concluded. This perhaps explains why a Congressional Research Service report in January 2025 observes that while perceptions of the United States and China vary widely across Africa, “China has drawn marginally or significantly more positive views regarding its economic and political influence or reputation.” Perhaps the Chinese are using their investment as a strategic weapon, just not in the ham-fisted, Spectre-like fashion that Mr. Gray and some of the senators at the hearing imagine.

If this is the case, the United States might be in very serious trouble. While China invests and gains some benefit from doing so, the United States bullies partners over trade and pressures our allies to sell us what is not for sale. A recent poll indicated that 85% of Greenlanders do not want to be part of the United States.

But what of China’s recent interest in the Arctic? What of their proclaiming themselves—proposteriously in the words of Mr. Gray—a near Arctic Power? What legitimate interest could they have there? Plenty it turns out.

While surely some of the witnesses for the committee understood, but probably felt it unwise to point out, the Northeast Passage, when it is navigable, cuts travel distance between China and the major ports in Northern Europe by 40%. Using this route requires specialized ships, especially ice breakers and the route would greatly benefit from enhanced navigational aids and ports. As the world’s second largest economy enmeshed in global trade routes, China cannot but be vitally interested in using this route and in the Arctic in general, especially as climate change opens new possibilities for its use.

In the Arctic, as elsewhere, China is seeking the maximum influence it can achieve at a reasonable cost. Its activities there should be closely monitored. They should not make us hysterical. Chinese actions are no justification for attempting to acquire Greenland against the will of its own people and our NATO allies. Besides, as specialists have pointed out, everything the United States wants in Greenland, it is already getting.

All the above criticism aside, the “Nuuk and Cranny” hearing was not a complete waste of time. I, for one, was surprised to learn that the entire American icebreaker fleet consists of three ships, one of which has been out of commission since 2010 and one of which has been out of commission since a July 2024 fire. As many of the witnesses testified this lack of icebreakers is a serious impediment to American interests in the Arctic whether they be commercial, security, or scientific.

The need for additional ice breakers has been apparent since 2010. Last summer Canada, Finland and the United States signed the ICE Pact, an agreement designed to allow the three countries to pool resources to build additional icebreakers. When Senator Amy Klobuchar asked witness Rebecca Pincus how the ICE Pact was going, Pincus responded that there were many implementation problems ranging from a lack of appropriations, to a shortage of skilled laborers, to trade restrictions.

Those all sound like better topics for a hearing of the United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation than a discussion of acquiring Greenland.

David Fields is Associate Director of the Center for East Asian Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of Foreign Friends: Syngman Rhee, American Exceptionalism, and the Division of Korea (University Press of Kentucky, 2019) and the editor of The Diary of Syngman Rhee, (published by the Museum of Contemporary Korean History, 2015,) and Divided America, Divided Korea: The US and Korea During and After the Trump Years (Cambridge University Press, 2024).

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.