RedNote, Deep Seek, and Education Exchange w/ Ryan Allen

- Interviews

Miranda Wilson

Miranda Wilson  Juan Zhang

Juan Zhang- 04/08/2025

- 0

While hot-button issues like Taiwan and tariffs get a lot of media attention, Dr. Ryan M. Allen talks with The Monitor about more personal connections between Chinese and American people, like our interactions through education and social media. Whether it be through viewing content on RedNote or engaging in study abroad programs, these kinds of exposures strengthen people-to-people connections. Dr. Allen shares his advice for Americans who hope to study abroad in China, encouraging American students to “be on the forefront of a possible new and more exciting bridge.” He thinks that the exchange is unequal; Chinese students are much more likely to learn English, study in the United States, and consume American media. Encouraging American students to learn about China is key to creating balance. Dr. Allen also shares his insights on DeepSeek, Trump’s policies on immigration, and “brain drain.”

Dr. Ryan M. Allen is the Associate Professor of Comparative and International Education and Leadership in the Educational Leadership and Societal Change Program at Soka University of America. His research centers on internationalization of higher education, EdTech, intersections between education and urbanism, and the East Asian region. He has published in numerous academic publications and popular outlets such as his most recent co-edited volume entitled Online Teaching and Learning in Higher Education during COVID-19: International Perspectives and Experiences (Routledge, 2021). He is the current host of the KIX EAP Podcast, where he interviews scholars, policymakers, and educators on national development on the Europe, Asia, Pacific regions. He writes actively on the SubStack page College Towns. He is also an active member in the Comparative and International Education Society, including the Study Abroad and International Student SIG, where he shares his passion for supporting international mobility and promoting study abroad. Before joining SUA, he was an Assistant Professor at Chapman University’s Donna Ford Attallah College of Educational Studies and Coordinator for the Chapman-Shanghai Normal University Doctoral Program. Dr. Allen holds a PhD in Comparative and International Education from Teachers College, Columbia University, an MA in International Relations from Yonsei University (Seoul, South Korea), and a BA in Public Relations from the University of Central Oklahoma.

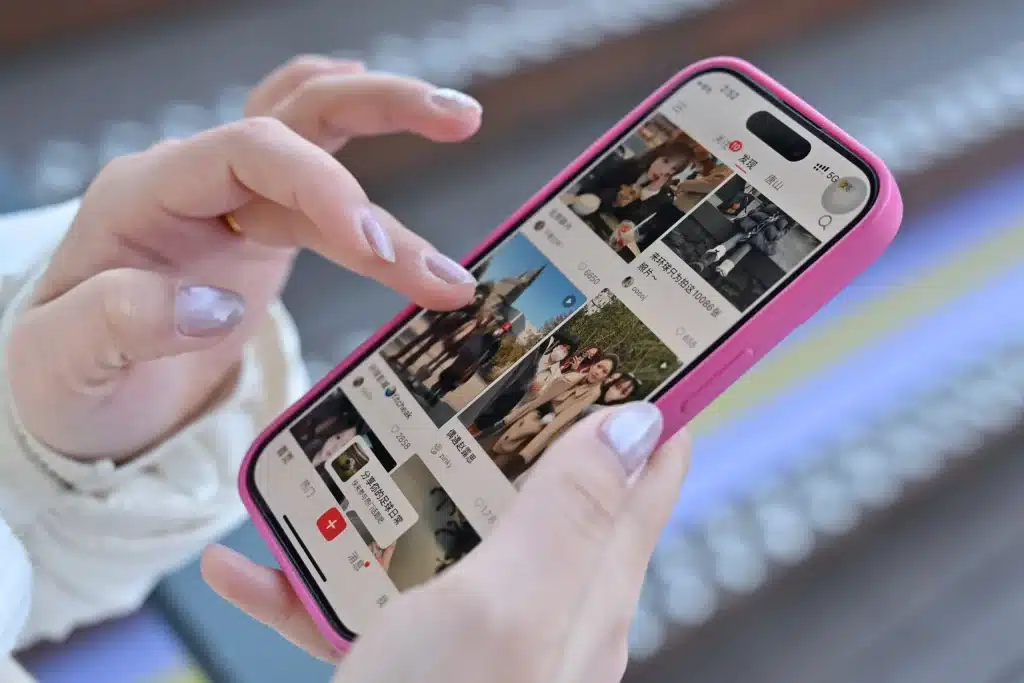

U.S.-China Perception Monitor (PM): In your article, you highlighted the rise of RedNote among users in the United States. What unique insights does RedNote offer that Western media or academia overlook?

Ryan Allen (RA): Social media in general is so much quicker and rawer than both media and definitely academia. Traditional media usually has a “If it bleeds it leads” type slant, so more negative stories get attention there. I am even more critical of academia in this space. Our writing is typically slow, inaccessible, and often behind paywalls.

Platforms like RedNote provide a more human-to-human connection. It’s not just passive viewing, but rather direct engagement. It was heartening to see Americans and Chinese react to each other’s content during the big flood of users migrating from the TikTok ban. I’m always trying to promote these kinds of humanistic connections. They are important, even if only digital.

One thing we should remember is that social media is often the glossy version of something. So, if American users are discovering China, they are potentially getting a mostly rosy version of that view. Now, I still think it’s better to see these kinds of insights, as they can gain a fuller picture once they start to learn more.

PM: The U.S. government had security concerns over TikTok, so it is somewhat ironic that American users would turn to a different Chinese-owned app. For that reason, do you think a ban on TikTok would be futile? Is the use of Chinese-owned social media apps in the United States inevitable?

RA: For Americans especially, we have a strong cultural aversion to our own government telling us what to do. It’s in our cultural DNA. So when they tell a generation that their favorite app is bad and must be banned, they are going to flock even more to TikTok.

I am always inclined to free speech, more communication, and less government control here in the United States. That might mean we can get taken advantage of at the fringes, but as a whole, it produces stronger outcomes in the long run. Even if it is a Chinese-owned app, I believe ultimately that the pros of the ban do not outweigh the cons. It opens a lot of other legal and political ramifications that simply aren’t worth it.

I think our culture and system are at their best when things are open and free. That is the competitive advantage that we’ve had for a long part of our history. It has brought us win after win on the global stage in terms of economy, culture, and immigration. Just because the United States lost the battle with the rise of TikTok currently, we shouldn’t abandon our principles so quickly. Social media is quick, and something will arise soon — a new generation will find their own thing.

Even the rise of TikTok was sort of happenstance. It was directly connected to the bozos over at Twitter shutting down Vine. All the creators had to find another video platform—TikTok obliged and innovated further. But I don’t think TikTok is dominant in the United States without the fall of Vine. We shouldn’t be so reactionary.

PM: What are some of the primary challenges that American students encounter when considering studying in China?

RA: I think there are considerable opportunities to study in China right now. It’s not 3 years ago when the country still had a lot of restrictions and flights were hard to come by. So there is mostly just a perception gap and motivation capacity about going there now. It had been becoming a bit more difficult to go to China, especially in terms of banking and foreigner restrictions in hotels, but those have apparently been eased up (I will see for myself in the summer). Although, for studying abroad there, those things shouldn’t actually be an issue, as students get housing and the international offices are good about getting students local bank accounts.

PM: What advice would you offer to American students who are interested in studying in China but may be hesitant due to current tensions or uncertainties?

RA: I would tell students to lean into the adventure and excitement of studying in China when tensions are high. This only means that we will need more people who understand the place in the future. Go there now, learn Mandarin, understand the culture and society, and get a job in either diplomacy or economic sectors. Both places are going to be the largest economies and most influential on the global stage for the foreseeable future. They might be more separate than in past eras, but they will still both be big independently of each other. Be on the forefront of a possible new and more exciting bridge.

PM: In what ways do you believe educational exchanges serve as a diplomatic tool to bridge divides and foster mutual understanding between the U.S. and China? What was your personal experience in this regard?

RA: I do, yes. I don’t think most Americans know much about China. The politics, history, and general society aren’t really taught in our school systems. People don’t travel there that much. The most they know is the Chinese food down the street, but they may not even realize it’s probably Cantonese and very different than Northern China cuisine. Some of this is changing, but it’s slow.

Conversely, I think the Chinese know a great deal about life in America. Students come here in large flows, our media (like Marvel movies) is consumed there in droves, and generally there is some awareness about American culture. This relationship is asymmetrical.

I used to teach and run a program that brought Chinese lecturers to the United States to do their PhDs. I coordinated language exchanges and field trips, and I was always touched by how much love and admiration locals ended up having when intersecting with my Chinese students. I am going to China this summer with a group of American community college students. So, I am excited to see their reactions to the country and people.

PM: One of your articles talks about the creators of DeepSeek and the fact that they were not educated in the United States. What do you think this means for the future of “Sea Turtles” (Chinese people who study in the United States and then return to China)? Will there be less of a risk of brain drain?

RA: To be honest, I think the brain drain has already long started. Many of the best and brightest students from China opt to attend Beida or Tsinghua, or even probably most other C9 League and broader former 985 universities. This is not 2004 anymore; the research capacity in STEM is on par with (and sometimes surpasses) the American peer institutions. In that article, I surprised myself when I found that even many of the advisors to the DeepSeek team had been trained back in China. So that’s the previous generation.

There will still be opportunities for so-called Sea Turtles. They just will not have the same kind of competitive advantage that previous generations had when they potentially returned. But I think this is already true for the most part.

PM: Could such well-known figures gaining their education from Chinese universities encourage more American students to study abroad in China?

RA: Perhaps, we could always use some encouragement. I think it’s a broader cultural shift needed in the United States to get us to study abroad more generally, and in China particularly. It won’t be just one thing to change this part of our current culture. I had another article talking about the soft power of China through video games, particularly Black Myth: Wukong, which was a smash hit when it came out. I think those kinds of cultural exports, piled together with social media like RedNote, are what will do the convincing. But it still takes time.

PM: The Trump administration’s recent policies around visas, immigration, and funding cuts to universities have forced international students to reconsider the benefits of studying abroad in the United States. How would having fewer international students impact American universities? What are some of the losses they would be facing?

RA: There are a lot of universities that rely on international students to come here and pay full tuition. This so-called cash cow stereotype of international students has been critiqued but is nonetheless how the population has been considered by various programs across the country. The loss of international students broadly will be tough for many universities, meaning more cuts and fewer opportunities for American domestic students.

One of the few exports that the United States has an imbalance in favor of us comes from higher education. We have a supply that the rest of the world gladly wants. It’s not manufacturing, but the service is massive to local and state economies. It is a self-inflicted wound to hinder this sector. It’s good for no one, basically.

PM: How can American universities encourage international students to attend amidst these challenges?

RA: One thing is money. It’s that simple. At one time, China was doing a lot of the funding for American students to study abroad either through the Confucius Institutes or other initiatives. There was so much heat on Confucius Institutes that they shut most of them down in the United States (and changed the name of the organization back in China). At the same time, the United States has cut funding for students going to China, namely through things like Fulbright. Unfortunately, nothing has filled this vacuum, leaving students without as much motivation to study there now.

I am glad to see that China has started doing some funding for international trips to China again, like the one I am attending this summer (I know of three other such trips). These kinds of short-term experiences are also what American students seem to like more than full semesters or longer full degrees abroad. So, I would like to see more funded opportunities, even if I still think longer-term trips are more beneficial.

I wish the U.S. government would recognize the importance of these types of exchanges. Unfortunately, I do not see our government putting money into these initiatives for the foreseeable future. It will have to come from the China side, which will only create heat once again.

Miranda Wilson is a contributing editor for the U.S.-China Perception Monitor.

Juan Zhang is a senior writer for the U.S.-China Perception Monitor and managing editor for 中美印象 (The Monitor’s Chinese language publication).

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.

Authors

-

-

Juan Zhang is a senior writer for the U.S.-China Perception Monitor and managing editor for 中美印象 (The Monitor’s Chinese language publication).