Quiet Hedging: Indo-Pacific Middle Powers’ Strategic Deterrence

- Analysis

Niño Ryan Embestro

Niño Ryan Embestro- 08/12/2025

- 0

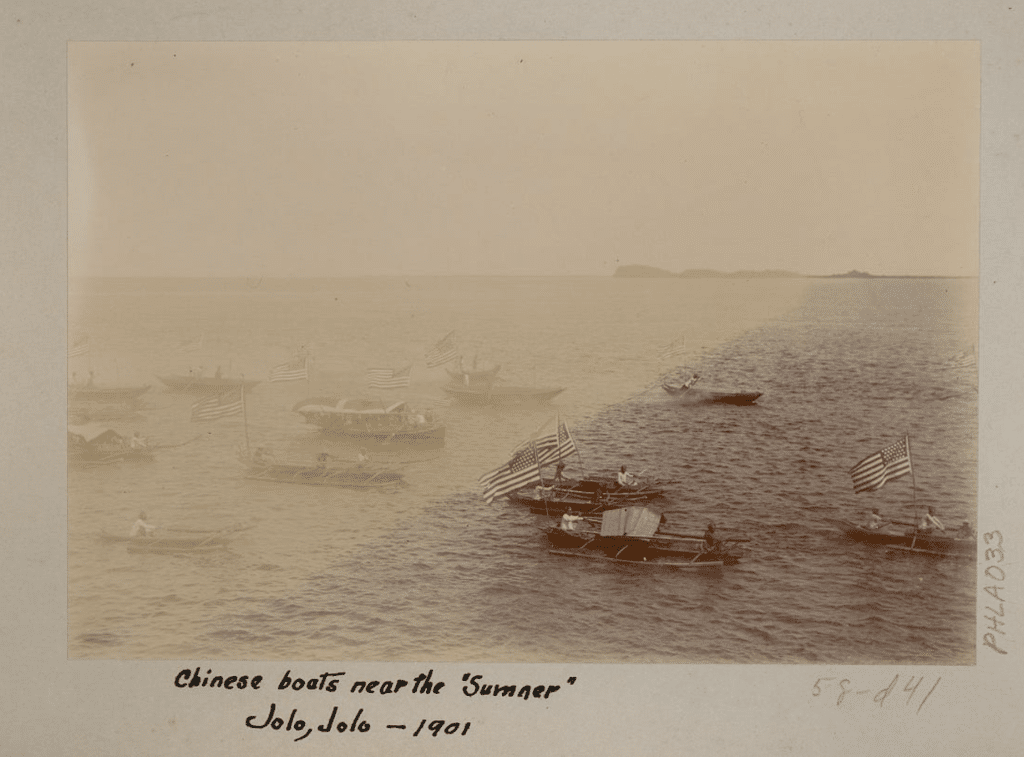

“Chinese boats near the ‘Sumner’: Jolo, Jolo.” 1901. Source. ‘Chinese boats’ most likely refers to the style, not the occupants.

As the Indo-Pacific region continues to be a theater of great power competition, middle powers have pursued strategic decoupling to achieve and reinforce a much better deterrence capacity. From bandwagoning with major powers, specifically the United States, these countries have sought alternatives to maximize their autonomy and lower major power leverage. In the area of political economy, countries such as the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia are recalibrating their strategic postures through economic diversification. Arguably, this policy is a counter-balance against China’s coercive economic behavior, which has been the long-time politico-economic challenge that its neighboring countries have faced. While there is still a presence of strong relations among middle and major powers, looking forward, middle powers in the region are increasingly leveraging asymmetric strategies.

This state behavior is warranted by the world’s now multipolar configuration, where foreign policies challenge bipolar or unipolar dominance. In the neoliberal context, the hegemonic thrust of major powers to increasingly influence global politics and economics further solidifies the motivations for middle and emerging great powers to pursue a pluralist foreign policy. One significant example is the case of India, which has positioned itself by championing the Global South’s interests while maintaining ties with Western and non-Western nations. This reflects its long-standing emphasis on strategic autonomy and underscores a broader regional trend where middle powers slowly hedge to further navigate the current global condition and pursue national interests.

As Keohane and Nye, Jr. put it in their work “Power and Interdependence,” the neoliberal context, which underscores the current global order, is evidenced by the complex interdependencies of political and economic variables, where states are both sensitive to each other’s needs and vulnerable to each other’s development. For instance, the dependence of tech giants on the United States and China on the semiconductor supply chain rooted in Taiwan, or the way oil politics demonstrates the influence of resources on global affairs, shows this current global dynamics, specifically the asymmetric relations that come with it. Multipolarity thus changes things, especially for middle power states, as it offers them alternative pathways for partnerships beyond the major powers. Therefore, both decreasing vulnerability and sensitivity, creating more avenues for middle powers to safeguard their national interests, and derisking from hard power maneuvering.

Middle Power Engagements and Leverage

As one of the chief objects of this strategic posture recalibration, economic diversification has become a strategy among middle power countries to deepen their ties with other middle powers, namely, Japan, South Korea, and India, an emerging great power. This strategy has become evident in some partnerships, such as trade and defence. Through these engagements, middle powers gradually reduce their dependence on major power influence and build long-term resilience against tie-shocks and strategic entrapments.

More specifically, in 2020, Japan allocated a greater share of its Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to the “ASEAN 5” economies, namely, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines, as well as the “Asian Tigers” of Singapore, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan than it did in mainland China, highlighting its intent towards regional diversification. South Korea, through its Korea-ASEAN Solidarity Initiative (KASI), similarly advances consistent engagement with ASEAN by “expanding its policy scope beyond economic and cultural domains to include security issues,” and therefore solidifying South Korea’s middle-power role in the Indo-Pacific through “proactive and diverse cooperation.” But compared to Japan and South Korea, India’s hedging is the most explicit with its open-door policy. It engages all and avoids taking sides in the U.S.-Russia and U.S.-China rivalries. In this case, India engages the United States, Australia, and Japan through the QUAD; China on significant trade and bilateral matters such as electronics, machinery, and chemicals; and Russia on energy and defense cooperation — ultimately upholding its strategic autonomy.

In addition, these hedging behaviors have signaled a shift from reactive posturing to proactive economic maneuvering. One major flashpoint that has signaled this move was the Philippines’ withdrawal from China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Under the Duterte administration, the Build Build Build Program, an infrastructure development project, advanced with the assistance of China’s BRI, which paved the way for new dams, bridges, and railways, attracting billions of Chinese investment and creating employment for thousands of Filipinos. However, due to funding delays on key infrastructure projects, thought to be influenced by the tensions in the South China Sea, the Philippines under the Marcos administration in 2023, pulled out of the BRI. Since then, the Philippines has engaged with Indo-Pacific middle powers such as Japan and South Korea on infrastructure development and other significant bilateral matters. More specifically, in 2023, the Philippines and South Korea signed a Free Trade Agreement, building on the Korea-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement. Therefore, illustrating a broader regional pivot toward a more pluralistic economic foreign policy, especially in an era of contested multipolarity.

However, far more than the hegemonic condition in the South China Sea lies a broader geoeconomic landscape shaping the region. For instance, Malaysia’s push for de-dollarization and support for BRICS+ has signaled an ambition that is aimed at gaining beyond the major power contestation. It is aimed at a far more fluid and decentralized economic order. The U.S. dollar has been the global reserve currency since World War II. This has favored the United States by making it easier to borrow money and impose painful financial sanctions. On the other hand, currencies such as Malaysia’s ringgit have been on a downward trend in 2022, which was said to be due to investors anticipating aggressive U.S. rate hikes from inflation and the weakening of the Chinese yuan. Malaysia and China have strong economic ties, noting this result. The point is that the weakening of the ringgit and its exposure to the current financial system have made de-dollarization a strategic necessity for countries such as Malaysia and the BRICS.

In addition, the BRICS’ effort to establish alternative financial mechanisms, including the creation of an international reserve currency based on a basket of currencies of the association’s member-countries, is meant as a protection against the sanction risks associated with settlements in dollars and euros. For Malaysia, this initiative offers a pathway to insulate itself from the negative financial impacts of the U.S. dollar and assert control of its economic future. For the current global order, this implies a turning point in the international system reflecting the multipolar world order.

Meanwhile, Vietnam continues to engage South Korea in fostering collaboration in science and technology, particularly in high-tech areas, research and development, and technology transfer, which ultimately signals a shift that middle powers are no longer reactive but are now strategically proactive in navigating geopolitical pressures. Despite Vietnam’s deepening economic ties with China, such as its railway construction project under the BRI, this engagement still implies its commitment to multilateralism. What this suggests is that hedging stands as a foreign policy of strategic flexibility. It allows for selective engagement, benefiting from major power cooperation without compromising its autonomy. But it also ultimately shows that the variations of national interests among middle powers highlight the varied expressions of their foreign policies, and each of them offers a distinct yet traceable pattern of hedging.

Furthermore, in a region wary of overt confrontation, economic maneuvering acts as a destabilizing force against coercive economic pressures. It acts as an additional bargaining lever for middle powers to diminish the influence of China’s coercive economic policy and the precarious effect of the U.S.-China Trade War. It acts, in other words, as a stabilizing force for middle powers to gain momentum in a region of consistent security concerns.

A Strategic Calculus

At its core, diversification thus functions as a form of quiet deterrence. It is not only transactional but normative. As middle powers craft a regional identity that is inherently geared toward a rules-based international order, such a policy not only enhances deterrence but also reinforces its normative legitimacy. So, while middle powers create geopolitical alternatives, they simultaneously decrease the grasp and hence complicate the coercive calculus of hegemons.

In the critical nature of the region’s security, this hedging behavior is particularly conducive to its strategic environment. It is not only cost-effective because there is a value-add, which is the long-term resilience of diverging from major power influence. It also broadens growth trajectories and reduces vulnerabilities from geopolitical or geoeconomic pressures. In other words, it dilutes asymmetric power maneuvering and equips middle powers with greater leverage in a contested domain in the South China Sea and the broader Indo-Pacific.

Niño Ryan Embestro is a graduate student in International Studies at De La Salle University with a focus on Asian Studies. Currently, he works at the Foreign Service Institute – Philippines.

The views expressed in this article represent those of the author(s) and not those of The Carter Center.

Author

-

Niño Ryan Embestro is a graduate student in International Studies at De La Salle University with a focus on Asian Studies. Currently, he works at the Foreign Service Institute - Philippines.