When Perception is Power: Countering China’s Courtship of Sub-Saharan Africa in the Trump Era

- Analysis

China-Focus-Editor

China-Focus-Editor- 08/13/2025

- 0

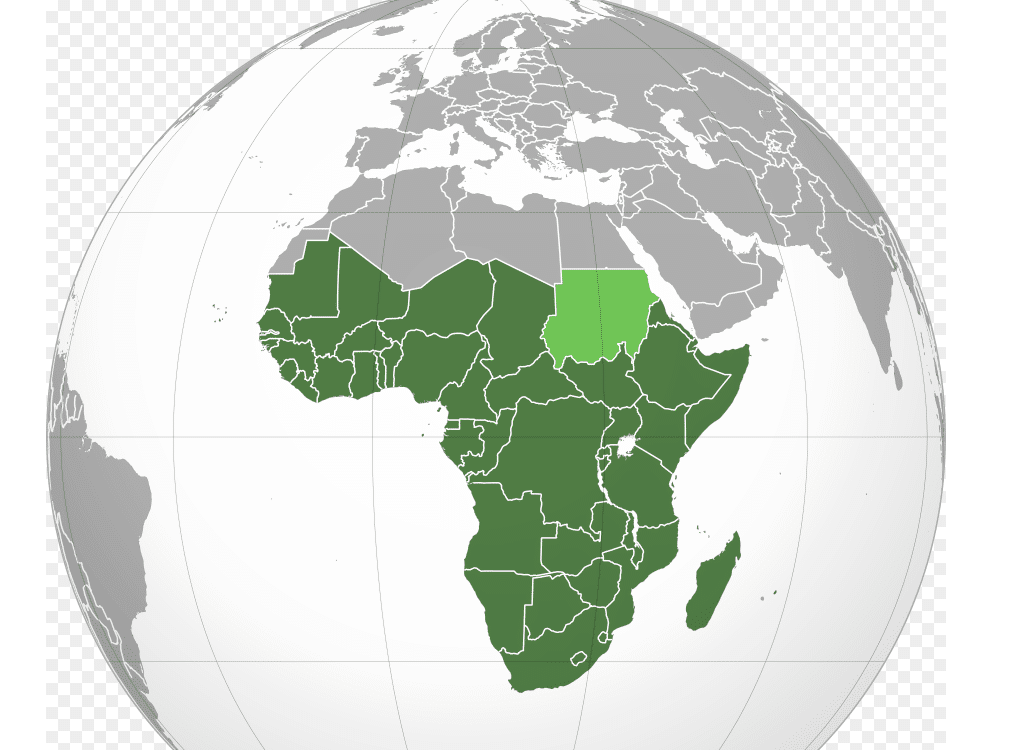

Source: geographical map of sub-Saharan Africa.

[The China Focus at The Carter Center, in cooperation with the China Focus at the University of California, San Diego, and the 1990 Institute, organized an essay contest in honor of President Jimmy Carter. This essay, by Elizabeth Nemitz of the University of Minnesota, received the Jimmy Carter Prize. Read more here.]

“Ghana is open for business,” declared Ghanaian president John Mahama at an event celebrating the upcoming 65th anniversary of China-Ghana diplomatic relations. Speaking at the Chinese Embassy in Accra, President Mahama affirmed China-Ghanaian bilateral cooperation in key developmental domains and sectors such as public health, energy, and education [1]. His remarks gesture to the embrace of Chinese enterprise in the sub-Saharan region, where for years, the U.S. has ceded ground. In Ghana’s case, Chinese investment in essential developmental targets has generated gains in important sectors of the national economy, with visible impacts in everything from construction to manufacturing, mining, agriculture, and trade [2]. As a result, Beijing has accrued a significant amount of political capital, deepening ties with African states as a part of a broader South-South alignment. Comparatively, the U.S. appears a distant or disinterested partner—one whose commitments to the region are less visible, less consistent, and less attuned to African priorities.

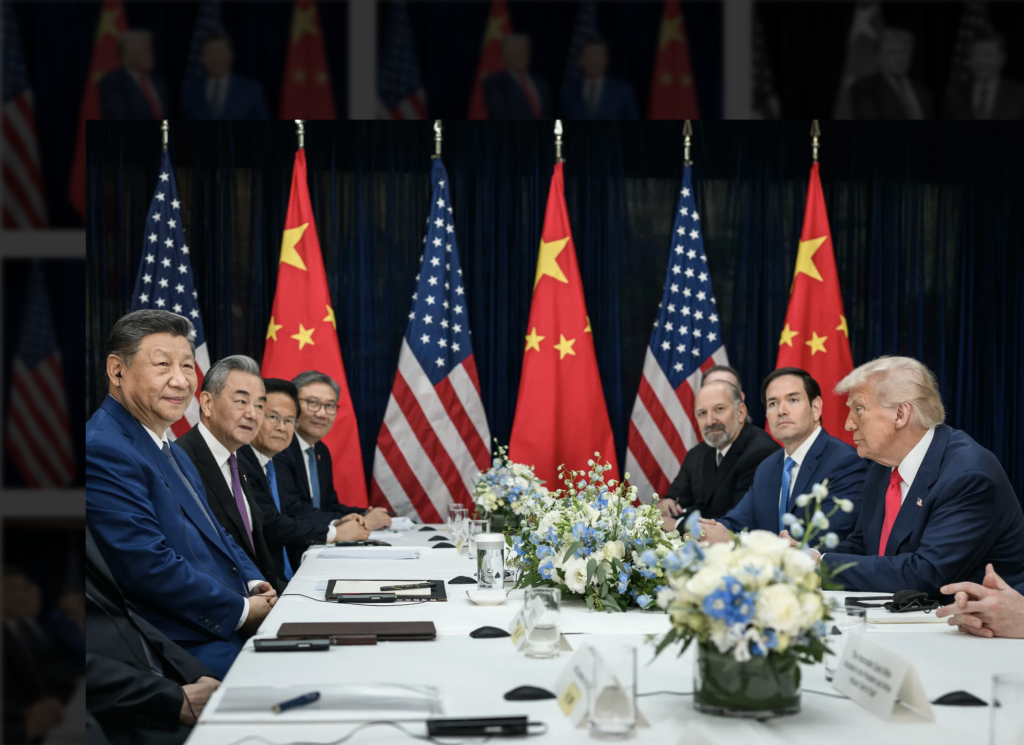

Donald Trump’s second term marks a turn in U.S.-China competition in sub-Saharan Africa. Early signs of declining U.S. engagement such as the hollowing of USAID, withdrawal of critical humanitarian aid, and an abrasive, Trump-style diplomacy indicate that his administration is poised to seriously scale down development programs and adopt a more selective pro-business strategy. The retreat from Africa comes at a time when the Global South’s faith in Western leadership is weakened, undermined by crises in international theaters like Gaza—recent provocations toward close Chinese ally, South Africa, over its genocide case against Israel and Afrikaner land rights reveal early signs of strain [3]. Thus, as the U.S. enters a second Trump era, it becomes apparent that the competition for Africa will not only be a battle of wills but also of perceptions, as Washington’s ability to counter China hinges less on coercive measures and more on the advancement of persuasive diplomacy efforts. China, for its part, has steadily expanded its soft power footprint in Africa across four domains: anti-colonial solidarity, educational exchange, economic engagement, and party-to-party ties. For the U.S. to stay competitive, Washington may need to fundamentally rethink its soft power arsenal.

Anti-Colonial Identity

In 2024, the 19th Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) Summit caught attention from some international observers, not least because a Chinese delegation was present [4]. While not a formal member, China’s attendance signaled a long-standing interest in overhauling the international architecture and reorienting geopolitical dynamics to better accommodate African states. Ahead of the summit, China’s Foreign Ministry hailed NAM as a platform for developing nations to “oppose imperialism, hegemony and colonialism” and reasserted a “shared future” for China and Africa [5]. Herein lies a consistent strategy: leveraging the politics of anticolonial internationalism to support a broader global restructuring.

In an ideological battle, China’s colonial victimhood grants it a rhetorical edge. Chinese politicians frequently invoke the “spirit” of the 1955 Bandung Conference, a watershed moment in NAM that cemented the shared struggle of Afro-Asian nations in securing postcolonial self-determination [6]. When confronting a multipolar future, China represents an appealing alternative to a Western-led order that has rendered African nations economically dependent and fractured across cultural and ethnic lines. For its part, Beijing is quick to remind the Global South that it, too, suffered from the same colonial subjugators and that it honors the principles of non-interference as the more responsible power. By tapping anti-colonial grievances, China has built coalitions among the Global South, strengthening its diplomatic leverage and voting strength. China is thus able to coordinate foreign policy priorities and advance a reinterpretation of norms anchored by African support inside an array of multilateral institutions. In return, China has supported African states’ measures to chip away at human rights protections such as withdrawals from the International Criminal Court (ICC) [7].

Uninspired U.S. foreign policy centered on humanitarian aid, military partnerships, and moralizing discourses around human rights has done little to dislodge China’s position as a natural partner to NAM [8]. The U.S. must thus re-consider how it projects its image. Traditionally, Washington has prioritized cooperation in security and public health and promoted democratic institutions and norms [9]; however, recent threats to Voice of America (VOA), the mainstay of American information outreach and a critical counter to global authoritarian influence, complicate efforts to diminish China’s sway in the region [10].

Still, Washington retains opportunities to recover. In its bid for the Global South, China’s anti-colonial appeal has taken a paradoxical turn, as it confronts accusations of neo-colonial behavior and irresponsible practices. Genuine concerns over “debt trap diplomacy” and premature deindustrialization among African exporters have damaged perceptions of its mission in the region [11]. More recently, China’s diplomatic image sustained a hit when a dam collapse at a Chinese-owned Zambian mine polluted a vital waterway. Chinese companies’ effects on local environments and heritage sites have elicited criticism from conservationists and rights groups, many of whom argue that corporations disregard labor, safety, and environmental regulations [12]. The Trump administration will capitalize on these vulnerabilities and double down on allegations of unfair business practices in an attempt to discredit Beijing’s motives in the region. In doing so, Trump will seek to rebrand the U.S. as a partner that empowers local agency and adheres to the loftiest standards of quality and transparency.

Educational Exchange

Traditionally a low-risk form of soft power, educational exchange has long been a cornerstone of China’s multi-pronged engagement strategy. Over the decades, China has exponentially increased China-Africa educational exchange in order to promote two-way development, improve people-to-people interactions, and highlight the spirit of South-South cooperation. In September 2024, the ninth conclave of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) convened African delegates who pledged to continue support for higher education collaboration covered by the China-Africa 100 Universities Cooperation Plan [13]. In 2018, over 80,000 African students studied in China, where government scholarships and vocational training programs assist students acquire essential skills to aid poverty alleviation and rural revitalization efforts back home [14].

For Beijing, increased inter-country knowledge production serves three major functions. First, it creates networks of scholars fluent in the Chinese language and culture with strong personal affinities for China. Second, it provides a conduit through which Beijing may spread its norms, government models, and political influence. Third, the facilitation of expert exchange programs, joint research and development projects, and expansion of language initiatives like the Confucius Institutes cements China’s place as an ally to African development goals. However,

China-Africa educational exchange brings turbulence. Specifically, incidents of anti-African racism within Chinese institutions have fueled friction between the African scholar community and the domestic populace, as evidenced by the 1988 mass anti-African demonstrations in Nanjing [15]. More recently, a college “buddy” system at Shandong University pairing some Chinese women with male international students—many of whom hailed from countries in the Global South—precipitated an outpouring of racist vitriol online [16]. Such incidents seriously jeopardize China’s soft power appeal, undercutting narratives of a mutual anti-colonial struggle.

In response, Washington might consider improving its own educational initiatives and increasing the attraction of the U.S. as a study destination for African students, especially those in STEM. A traditional hotspot for international education, the U.S. has profited significantly from foreign-born “brain gain” and contributions made to its knowledge economy vis-à-vis other developing nations. However, the recent spate of student visa revocations and heightened scrutiny of Palestinian causes, a powerful mobilizing force in the Global South, has sown fear among international students and injured perceptions of accessibility for future scholars, posing setbacks for the U.S.

Economic Engagement

For the past two decades, the financing of major infrastructure projects has provided the fulcrum of China’s economic engagement with African states. According to Boston University’s China’s Loans to Africa (CLA) Database, Chinese lenders inked 1,306 loan deals amounting to $182.28 billion with 49 African governments and seven regional institutions from 2000-2023 [17]. Chinese lenders have employed a variety of financing models for large-scale infrastructure projects in countries like Angola, Ethiopia, and Nigeria, offering nations a chance to correct shortfalls in physical infrastructure in exchange for exporting precious mineral wealth for processing abroad. China’s flagship development project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), dubbed “one of the most ambitious infrastructure projects ever conceived,” testifies to the brilliant evolution of Beijing statecraft, as Xi Jinping seeks to redraw trade maps and secure energy supply routes that de-center the West [18].

China and the U.S. share a vested interest in sub-Saharan Africa’s rich endowments in oil, gas, rare earth minerals, and untapped human capital. With birth rates in China and Western nations set to diminish in the future, Africa will be responsible for around 60% of global population increases between now and 2050 [19]. Moreover, as the onslaught of climate change further underscores the exigency of green energy solutions, the region’s extensive mineral and energy resource portfolio will attract nations aiming to bolster green technology industries and high-productivity sectors. In 2024, the Biden administration delivered $250 million to the construction of the Lobito Corridor, a railway connecting Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo to the Angolan port of Lobito, through the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) in an attempt to respond to China’s infrastructure footprint [20]. But the U.S. lags behind overall, while China has created inroads into diverse sectors, from expanding its media and telecommunications presence to building space partnerships that aid its surveillance capabilities [21]. Currently, the imposition of U.S. tariffs may push African nations closer to China, which remained a top African trading partner for the fourteenth consecutive year in 2024 [22].

However, as international analysts have noted, Chinese financing hardly provides the panacea for African development challenges. Models predicated on raw material exports not only fail to produce sustainable development trajectories but also undermine local industry, stifling the potential of Africa’s nascent manufacturing sectors [23]. Furthermore, concerns over project quality and transparency, combined with trends of hostility and “self-segregation” among Chinese-led businesses, have decreased trust in Chinese partners [24]. Lastly, economic woes at home, fueled by a sluggish COVID-19 recovery and rising youth unemployment, have spurred Beijing to scale down lending for overseas mega projects in an effort to de-risk. The defaulting of major real estate firms like Evergrande in 2021, which calcified the pitfalls of real-estate driven growth, among other economic challenges, has prompted Beijing to pursue a fundamental economic restructuring. With Chinese investment dwindling, China’s pursuit of a dual circulation strategy prioritizing high consumer spending supported by selective overseas investment will weaken its economic pull in sub-Saharan Africa.

Falling Chinese investment marks a propitious time to target African states’ core interests. Yet so far, Washington has struggled to seize the moment. Reauthorizing the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), an agreement up for renewal this year granting eligible nations duty-free access to the U.S. market, would be vital to stimulating targeted bilateral trade, but protectionist measures and high tariffs—including a 50% tariff on export-reliant Lesotho—have jeopardized its future [25]. Additionally, while expanding Prosper Africa programs to coordinate U.S. agencies and streamline pathways for strategic two-way economic partnerships might help sustain economic partnerships, recent cuts to USAID could blunt their potential [26].

Seeking to present itself as the fairer business partner, the U.S. may take meaningful steps to support market-driven growth and the cultivation of favorable business environments in lieu of a top-down aid model [27]. As the ripple effect of a flagging Chinese economy emphasizes the need to diversify African economies, the Trump administration can promote local resiliency by harnessing private investment to target non-extractive sectors and support African processing and manufacturing, minimizing dependency on the Chinese export market—but the future of U.S.-Africa cooperation remains uncertain. With African nations scrambling to negotiate, the U.S.’s interest in resources like rare earth minerals will likely provide one of the only points of alignment moving forward [28].

Party-to-Party Ties

Overshadowed by infrastructure and trade-related headlines lie China’s connections with foreign parties and political elites across sub-Saharan Africa and the globe. Currently, the CPC maintains relations with around 500 political parties from more than 160 countries [29]. Through channels like the International Department of the Communist Party of China (ID-CPC), China has assembled complex networks and political linkages to facilitate party-to-party exchange in matters of state governance and party-building. A contrast to Mao-era diplomacy, which emphasized the legitimacy of the CPC as a state organ, the current emphasis on elite ties—including cadre training, professional workshops, and scholarships for African political and military elites and youth party delegations—aims to promote China’s governance models and advance its strategic interests [30].

A critical pillar of Beijing’s strategy, elite exchange thickens up the other aforementioned dimensions of soft power, allowing China to disseminate geopolitical narratives regarding the political status of Taiwan and Hong Kong. After the passing of the 2020 national security law in Hong Kong, a statement backing China’s decision included fifty-seven signatories, twenty-five of which hailed from the African continent. In exchange, African elites gain skills from workshops and seminars targeting opposition management, poverty alleviation, party organization, and surveillance technology, among other topics. Resource-sharing of authoritarian tools such as facial recognition technology incentivizes the bolstering of dissident monitoring and citizen surveillance systems, strengthening oppressive African regimes [31].

The U.S. is losing ideological space to the spread of authoritarian influence. With Beijing dedicating the time to cultivate meaningful partnerships, Trump’s transactional, short-game approach to bilateral partnerships may not suffice. While Washington will continue to promote democracy, free-speech, and citizen-responsive governance methods as alternatives to Chinese authoritarianism, it risks folding to Beijing in the realm of direct ideological influence as Trump significantly pares down U.S. engagement.

The Future of U.S. Engagement in Africa

As Trump slashes U.S. cultural diplomacy capabilities, the structural capacity of the U.S. to compete in the region could erode further, permitting China to consolidate gains in countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia, Angola, and Nigeria. Amid the threat of tariffs, tangible levers such as the reauthorization of AGOA and the expansion of commercial ties and business partnerships are critical to sustaining a foothold [32]. At the same time, China faces threats of its own, as it grapples with charges of neocolonialism abroad and economic headwinds at home. In such a shifting landscape, Trump’s transactional approach could paradoxically compel African states to shift away from aid dependency and recalibrate based on their own priorities.

Yet, even in the context of a U.S.-China “re-scramble,” sub-Saharan Africa is far from a passive observer. To define the region as a mere battleground for outside powers discounts the agency of African countries in leveraging external engagement and configuring Chinese-exported norms and development paradigms to maximize their own interests [33]. The dynamism of the geopolitical horizon grants African states opportunities to assess local needs and hopefully chart the future of regional development on their terms. As it aims to balance a transactional Washington and an economically-weakened China, sub-Saharan Africa is far from out of the game—and it may very well surprise us.

(The notes in the text are available upon request from the editor.)