An Interview with Yun Sun: The Trade War’s Not That Bad for China

- Interviews

Tyler Quillen

Tyler Quillen- 10/15/2025

- 0

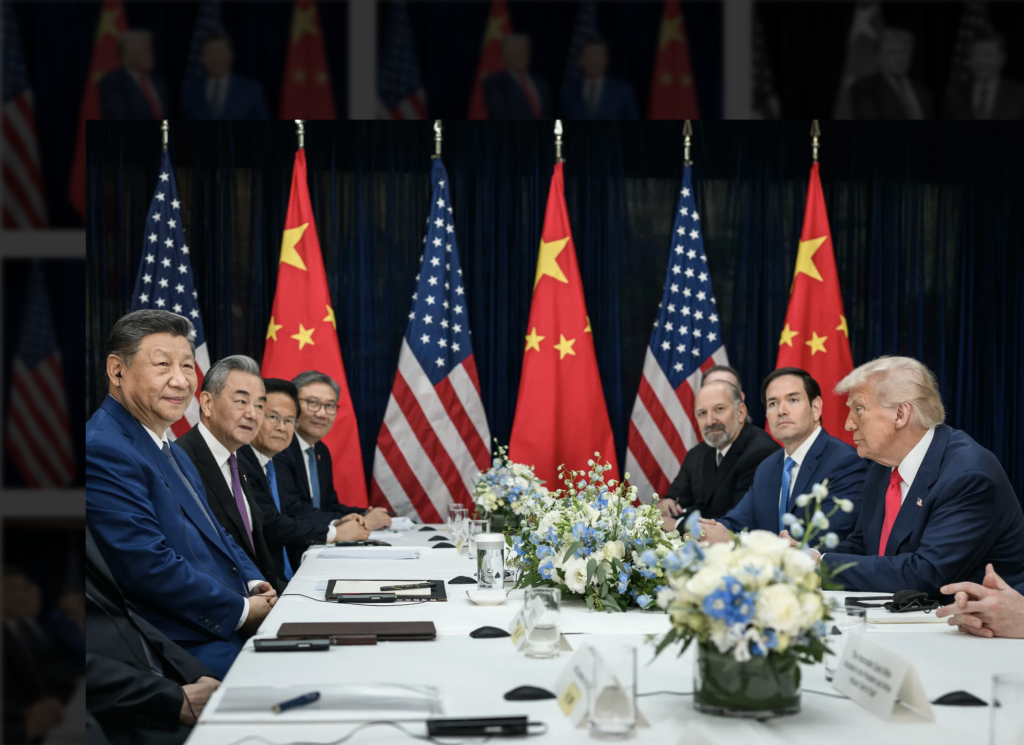

The second Trump administration has brought a flurry of changes to the international ecosystem, particularly in the realm of trade. As President Trump seeks to rebalance America’s relationships with partners and rivals alike, the world’s other main superpower, the People’s Republic of China, has found itself in an unexpectedly comfortable position relative to its primary strategic competitor. With a possible meeting between President Trump and President Xi forthcoming, issues such as tariffs, trade negotiations, Taiwan, and diplomatic messaging sit at the forefront of minds in Washington and Beijing. Now, the global community watches with bated breath as the stability of the world’s most important bilateral relationship hangs in the balance.

To untangle this web of messages, actions, and interests, The Monitor’s Tyler Quillen sat down with Dr. Yun Sun to gain her insights regarding recent shifts in cross-Pacific relations. Sun is a Senior Fellow and Director of the China Program at the Stimson Center with expertise in Chinese foreign policy, U.S.-China relations, and China’s relations with neighboring countries and authoritarian regimes. Sun brings with her further experience as a Visiting Fellow at the Brookings Institution, years as the China Analyst for the International Crisis Group based in Beijing, and work on U.S.-Asia relations in Washington, D.C. We asked her to discuss the causes of current trends, the prevailing rationale in Washington and Beijing, and how to read the proverbial tea leaves of what may lie on the horizon.

Beijing adjusts to Trump 2.0

Tyler Quillen: To start, in the lead up to the second Trump administration, what was Chinese leadership expecting? How have those expectations evolved as the Trump administration has taken power and now that the administration has really got into swing?

Yun Sun: I think between the November election last year and January 20th, the assessment on the Chinese side of the second Trump administration was that Trump would pick up U.S.-China relations where he left it in January of 2021—and that was not a good place. In 2020, we saw bilateral relations in free fall. And then, by the peak of the greater power competition, we saw that the Biden administration basically continued that policy. So, I think for the beginning of the second Trump administration, Beijing was certainly expecting a significant deterioration and even turbulence and instability in the bilateral relationship. I think those expectations got affirmed at the beginning of April when the Trump administration launched the escalation of tariffs against Chinese exports to the United States. So, the sense in China was “Well, we saw this coming. This is not surprising, and this is really going to be a difficult battle to fight in U.S.-China relations.”

But then, by the end of April, when it was very clear that both sides were trying to de-escalate the tariff war and the U.S. side was particularly interested in de-escalation, that paved the ground for the rounds and rounds of trade negotiations as we have seen in Geneva, followed up in London, Stockholm, and most recently in Madrid. So, I think we have seen the stabilization of the relationship since the Geneva meeting and the Geneva agreement. Now I think the expectation on the Chinese side is that this could become a more stable and positive interaction or positive period in the bilateral interaction compared to the previous eight years.

TQ: What are some of the reasons the PRC has found itself in a surprisingly strong position amidst trade negotiations with the U.S.? Do these stem more from the domestic situation in China or the United States, or should we understand China strengths as coming from the U.S.-China relationship itself?

YS: I think the answer lies in which side has more capability and more ability to withstand a war of attrition, because when we look at the trade war and trade negotiations, it’s a long process. It’s not a battle that will be won overnight or over a week. In a trade war we’re looking at which country and which market, and by that definition, which people have a higher capability to endure the pains of the trade war. And one would assume that the answer has to be the Chinese, because the Chinese economy has been so dependent on exports. I think that this thought is certainly correct, but it also neglects some important facts. This thing comes down to public opinion.

I think the Chinese have a much higher capability to endure the pains that have been imposed, not only because of their authoritarian political system but also because of the government’s ability to control the information the population gets to access. This is quite important in this domain, because, just like during the first Trump administration, the Chinese narrative domestically has been that China is innocuous, that this is completely the U.S. changing its position on China. So, yes, there has been the escalation of tariffs, and the Chinese people have to take the pain or the hit from the U.S. policy, but it’s not Beijing’s fault. So, I think the experience that we have seen is that, when there’s escalation of tariffs between the U.S. and China, the Chinese side has been very adeptly turning it into an instrument to agitate or stir up domestic nationalism in support of the government’s move. Well, in comparison on the U.S. side, the story is not so intricate. In the U.S., consumers and industries will react very directly to what they perceive to be the impact of the trade war on them, on every individual. So, in this sense, I would say that just looking at the public opinion side of the story, the Chinese are in a better position to withstand the impact of the trade war.

Also, remember that we talked about the Chinese being the supplier and the U.S. being the consumer. When we had the trade war, we had a supply shock, and we also had a demand shock. So, it’s an impact on both sides. But the problem with this equation is that, for the Chinese, the demand shock that they experience is not immediate because they have been trying to build up transshipment centers, alternative trade routes, backdoor access into the U.S. market for the past seven years. So, for China, there’s an impact, but the impact is not immediate. But, for U.S. consumers, it’s a supply shock. Once you cut out the massive supply from the Chinese suppliers, the U.S. does not necessarily have an alternative supplier to turn to—that’s how massive the Chinese exports to the U.S. have been.

So, you would assume that if U.S. stops buying, then of course it’s the supplier that’s going to be the one paying the most significant cost. But, in actuality, what we have seen is that U.S. consumers are suddenly looking at a shortage of supply and sudden high increase of the price that they have to pay. So, I think that has much bigger domestic political consequences for any administration, especially for the Trump administration that says they’re trying to make America great again. I think that is a particularly interesting angle that people should be looking at when they evaluate who has the bigger ability to withstand the impact of the trade escalation.

The instability of Trump’s China policy

TQ: To talk more about this change that we’ve seen in the demeanor of the Trump administration, why has the Trump administration changed so much between Trump One and Trump Two, particularly in its position towards China?

YS: I would not draw the conclusion that it is entirely different just yet. We’ve seen some changes in terms of tactics: there’s no reference to Taiwan, there’s no reference to great power competition. But we should also bear in mind that Trump is a very practical and transactional president. Now I think the perception is that his top priority is trade negotiation with China. So, things are being framed in a way that trade negotiation would not be hindered by any other issue at this moment, but this priority could change, and it could change very quickly. I think that’s part of the reason why China is not in a terrible hurry to have a trade deal signed, because what’s next if there is a trade deal?

I think we also have to look at how and where the money is being spent. When you look at the U.S. national security strategy, I’m prone to believe that China is always going to be a significant issue in the U.S. national security strategy, even if the Trump administration so far has not talked about the great power competition. So, we’ll have to see, where is the money being spent? And what is the policy? I think from that we potentially will see a lot of continuity instead of discontinuity.

I think another issue that has changed between Trump One and Trump Two is the dynamics within the administration. With the second Trump administration, what we have seen is absolute loyalty. People will follow his instruction; they will follow what he defines as the administration’s priority, without any criticism or without any second thought. But I think the same was not true with the first Trump administration, especially on China policy. For the first Trump administration, a lot of times it was the cabinet members that were leading the China policy instead of President Trump leading it. And for the cabinet members, I think their individual aspirations and their individual priorities came to transpire in that policy making and policy implementation process. So that is definitely a very different atmosphere compared to the second Trump administration. With the second Trump administration, I think as long as President Trump refrains from criticizing China—as long as he prioritizes the trade deal and the transaction with China—I don’t think that his cabinet members will be in any way challenging those priorities.

At home in trade chaos

TQ: Building off of that, how have all of these factors changed how China engages with the U.S. and its administration, and vice versa?

YS: I think the Chinese approach has been quite clear and I think the fundamental Chinese approach has not changed. But this is an interactive process, so the actions of the U.S. and the Trump administration evidently has impacted how China responds to it. This time around, in terms of the Chinese reaction to the second Trump administration, I would define it as retaliation in kind. What I mean is that when the U.S. imposes a tariff of 145%, China will counter impose a 145% tariff on the U.S. exports to China. And when the U.S. puts Chinese companies on their sanction list, you will see China doing the same thing to U.S. companies. So, it’s retaliation in kind and it’s largely proportional. But this also means that when the U.S. administration expresses its goodwill, China also responds in a highly positive manner. For example, we’ve seen the two leadership phone calls, one on June 5th, the other one on September 19th, and both of them were extremely positive interactions. I would say that for from the Chinese side, the Chinese don’t see themselves as a first mover. But, they have positioned themselves to respond in the same manner they perceive they have been acted against, whether that is negatively or positively.

For the vice versa, I think so far, the Trump administration has been responding in a similar manner. When there’s goodwill from China, the Trump administration would respond with his own goodwill. But when China is perceived to not be playing ball, like for example on the rare earth export licensing to U.S. companies, I think we also see that the U.S. is willing to bring out the stakes in order to make the relationship go in the directions that is in line with U.S. interests.

TQ: In your recent Foreign Affairs article, you talk about how China feels comfortable with competition in the space of economics. I’m interested to hear why this is the case.

YS: Well, that’s because this is not the first time that China has to deal with this. The first time that China had to deal with this in this relatively dramatic manner was actually in 2018. That’s when the trade war first started. And if you look at it during the Biden demonstration, none of the tariffs imposed during the first Trump administration were ever removed. So, I think the Chinese would argue that they have been living under the trade war since 2018. They have been adjusting their domestic economic cycle and their export model to deal with this reality of tariffs from the United States. The current tariffs are already much higher than before and potentially will go even higher. I think that’s why when we look at the overall state of Chinese global trade the U.S. is no longer their largest trading partner. China trades more with ASEAN and Europe compared to their trade with the United States, which means that China has been building this cushion of alternative markets and alternative consumers of Chinese products.

And then we also know that, because trade is globalized, while the U.S. is not importing from China that does not mean that the U.S. does not import at all. There was a whole concept of friend-shoring. So, we are importing more from our partners, countries like India, countries like Vietnam, but these countries do not have the whole supply chain capability like the Chinese market has in order to produce the whole supply chain of products. One example you can think of is a car that General Motors used to make in China. A car requires 2000 parts; you can move the production line to Vietnam, but Vietnam as a single country does not have the ability to produce the same 2000 parts in order to assemble the car. So, where do those parts come from? China turns out to be the only market that has that whole supply chain capability. So, it turns out that while China is still exporting to the United States, just not directly—China is exporting through third countries.

And of course, there’s also the caveat between efficiency and security. If you want the supply chain to be secure, if you want to make everything here on U.S. homeland, it’s going to be much more expensive because of the globalized supply chain and also because of the cost to produce things here in the United States, even just looking at the labor cost alone, it is significantly higher. This is why the U.S. still has a demand to import these goods. And it may not be directly importing from China, but it’s importing from trading partners of China. This is why the transshipment issue and the issue of backdoor access into the U.S. market have become so significant.

And so far, we have seen that the Trump administration has vowed to stop the transshipment. But then you have the problem of, how do you decide what is the component of the countries of origin and what is the Chinese component in a finished product? And, more importantly, who is going to enforce those adjudications? Does U.S. customs have the capability to inspect all the containers coming to the U.S. and determine for each product what is a Chinese component, what is a local component? This is a very big endeavor, so it does have issues of practicality embedded in it. So, this essentially means that for the Chinese trade with the United States, it stopped, but not entirely. Instead, it’s taking on other forms, maybe not direct trade, but indirect trade. I think that’s why the Chinese feel that they’re a little bit more confident about their ability to withstand this impact from the trade war—because they have been preparing for it.

Where does Taiwan fit into a possible new U.S.-China relationship?

TQ: If the current positive signals from the U.S. are in fact not meant to be temporary, how can Washington communicate this to Beijing?

YS: Well, for Beijing to evaluate Washington’s intentions, they always watch for what Washington says and what Washington does. So far, we have seen a lot of positive words and a lot of positive interactions. I think for Beijing to believe that this is not meant to be temporary, they want Washington to buy into and accept certain narratives that Beijing has been hoping for Washington to embrace for years, if not decades. And here I will say that the issue of Taiwan is at the top of the list. Beijing wants Washington to oppose Taiwanese independence. Beijing wants Washington to say that the United States welcomes, accepts, and supports peaceful unification. So, if Washington is willing to go that far, basically to change the fundamentals of the U.S. policy towards the One China Policy, I think Beijing will be convinced that maybe this is more permanent than rather than temporary,

But this is a very difficult campaign and, honestly, I don’t know if U.S. should signal that these changes are permanent either. As a great power, you want to maintain the maximum flexibility of your policy. So, why would you want to signal your enemy that I’m buying into a position and I’m never going to change? Personally, I don’t think that is in the U.S. national interest. And, also under that framework, I would say that a lot of these things that Beijing says it will need for the U.S. to communicate its positivity are not necessarily in the U.S. interest either. So, I don’t think the U.S. should necessarily go there.

TQ: What should be expected from the possible forthcoming meeting between President Trump and President Xi? Do you think we’ll learn anything new about long term goals in Beijing or Washington?

YS: I think so. Well, first off, when there is a leadership summit or a leadership phone call, it is guaranteed that it will be positive. At least between U.S. and China, it will be positive because working level officials have already worked out all the working level details; what will be agreed, what will be the deliverable, and what will be the key message to the rest of the world. If there’s no agreement on the working level, there would not be a leadership summit. This is why whenever we have a visit or we have a leadership phone call or a side meeting, the messaging is mostly positive.

Are we going to learn anything new about long-term goals in Beijing or Washington? I think that comes to the pulling and hauling I just mentioned. There are certain things that Beijing wants Washington to commit to. But is Washington going to concede? Is Washington going to accept? Or is Washington going to make a counteroffer? The end result will turn out to be less satisfactory than what Beijing originally asked for, but it’s still better than nothing. So, I think anything new will really be lying in the nuances of the wording and technicalities that we can see from these upcoming meetings. And also, remember this will not be a state visit, this will be the upcoming meeting in South Korea on the sideline of APEC. So, it’s a third country location site meeting alongside a multilateral meeting, which means that the time that they will spend together is going to be limited. They probably will have one face-to-face meeting and will make a statement based on that meeting. I think anything that is nuanced from those statements, and the details of the meetings are going to tell us how far each side is pushing and how amicable the other side is toward the position that the other side is pushing for.

TQ: Outside of the scope of just Beijing and Washington, what does all of this mean for Taiwan? How should we expect Taiwan to react to the current trajectory of U.S.-China relations?

YS: I think Taiwan has been put in a really uncomfortable position because, well, everyone can read the news, right? There has been a reluctance in Washington to demonstrate its support of Taiwan, no matter what that support is defined as. So, for Taiwan, there’s a natural anxiety about the future of the U.S. commitment. But then again, I think the question is how sustainable is this? How long lasting is this? Is this a permanent change of position, or this is just a temporary or tactical shift on the U.S.’s part in order to facilitate the success of the trade negotiation? There are a lot of uncertainties for Taiwan. I know that there have been a lot of discussions about maybe the U.S. and China are planning a grand bargain over Taiwan in their upcoming leadership summit. I think there are certainly issues that China wants to push for; they want the U.S. to make certain declarations about its position on Taiwan, like I mentioned, to oppose Taiwan independence, and to support peaceful unification. So, those are things we know that that the Chinese want the U.S. to do.

But I think any pragmatic and realistic policy makers in China will realize that the U.S. will not give up Taiwan. A grand bargain at the cost of Taiwan is not going to happen because, even if you just think of President Trump as a businessman, what a businessman does not do is to give up his leverage and his bargaining chip from the beginning of the negotiation. So, as long as the Trump administration or President Trump identifies Taiwan’s significance and value are irreplaceable and indispensable for China, I think the instinct will be to hold Taiwan closer as a card rather than giving it up to the Chinese. So, on this particular issue, I don’t see that there will be a campaign to abandon Taiwan.

But we also know that the U.S. has policy priorities on Taiwan itself, like for example for Taiwan to increase its defense budget to purchase more U.S. weapons. Also, in the statement by the Secretary of Commerce Lutnik last month, we’re seeing that he’s arguing that Taiwan should transfer some of the semiconductor chip industries and manufacturing capabilities to the United States. That’s a separate game between the U.S. and Taiwan that is not directly related to U.S.-China negotiations. So, I would say that this means uncertainty for Taiwan and some really uncomfortable interactions and security anxieties. And I think it’s not going to be an easy sell for Taiwan because Taiwan has been pushed and will continue to be pushed to bring out more for the United States in terms of purchasing U.S. products and also transferring some of Taiwan’s industrial capability to the United States. So, it’s not going to be a comfortable and easy ride for Taiwan, but I will not go as far as to say that somehow the U.S. is going to abandon Taiwan and let China have its peaceful unification at this point.

What to watch

TQ: What do you think are the most important signals in the near- to medium-term for the U.S.-Chinese relationship that people should be looking out for? In terms of things like the possible upcoming meeting between President Trump and President Xi, as well as other interactions between Washington and Beijing, what should people be looking for to understand what may come in the next?

YS: Like I mentioned, if there’s going to be a meeting or a summit, it most likely will be positive. I cannot imagine that they would have a meeting and suddenly there’s a breakup from the meeting. So, as long as there are senior level communications, I think that is a sign that the relationship is going relatively positively and on the track of stability. But, if we perceive that there’s a lag, and in the same vein, if there’s a lack of senior level communication, then that would indicate that there are problems working level officials cannot resolve and therefore the two leaders are not talking to each other and that could be an indicator of things being in trouble. I would also look for U.S. references or focus on negative issues such as Taiwan, Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong, Chinese military operations in the South China Sea, China’s human rights, and the Chinese Communist Party. All those political angles, once they come into play, become extremely difficult to reverse and those in most cases have carried a much more significant negativity for the bilateral relationship than the trade talks. With trade talks, you can revoke or rescind. But for the political messaging that targets Beijing or targets the Chinese Communist Party, I think those are perceived as a much more dire and serious offense. So, I would watch very carefully for what political messaging outside the trade talks Washington and the Trump administration engage in.

(Image Source)

Author

-

Tyler Quillen is an intern for China Focus at The Carter Center and a graduate in International Security from the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Sam Nunn School of International Affairs.