An Interview with Ji Li: Insights on Chinese Multinationals and the U.S. Legal System

- Interviews

Alice Liu

Alice Liu- 10/22/2025

- 0

“Government Bureau.” 1956. George Tooker. Source

In 2018, the case involving Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. and Meng Wanzhou made headlines worldwide, after the U.S. government accused Huawei of bank fraud. Occurring at the height of the U.S.–China trade war, the case marked a new phase of tightened U.S. scrutiny and control over Chinese enterprises.

Today, The Carter Center hosts Dr. Ji Li to discusses his newly published book, Negotiating Legality, which sheds light on how Chinese multinational corporations adapt to the U.S. legal system and navigate growing political pressure. Dr. Li underscores the importance of cultivating legal awareness, pointing to the structural and cultural hurdles that often prevent Chinese MNCs from acting in their best interests. For anyone seeking to do business in the United States or interested in Chinese business and law, this interview offers invaluable insights.

Ji Li is the John & Marilyn Long Professor of U.S.-China Business and Law at the University of California, Irvine. His expertise lies in Chinese law and politics, comparative law, and contracts. Prior to joining UCI Law, he worked for several years at Sullivan & Cromwell LLP in New York. Dr. Li’s publications include Negotiating Legality (2024) and Clash of Capitalisms (2018), both of which examine how Chinese multinational companies, including those owned by the Chinese state, adapt to U.S. legal and regulatory institutions.

Alice Liu: Last year, you published a book called Negotiating Legality, in which you examined how Chinese companies navigate the U.S. legal system. What do you think is the most important takeaway from this book, and how did you conduct your research?

Ji Li: The main takeaway is that Chinese multinationals face significant challenges in adapting to the U.S. legal system, largely because the United States and China have markedly different legal traditions and cultures, particularly in the area of dispute resolution. Their ability to adapt varies systematically according to ownership structure, listing status, investment duration, and other key corporate attributes. For example, whereas U.S. firms tend to make litigation decisions primarily based on cost–benefit calculations, Chinese firms often attach complex social meanings to litigation. State ownership further complicates matters, frequently slowing dispute resolution and introducing non-commercial considerations into decision-making.

Despite these challenges, many Chinese multinationals adapt by relying heavily on local counsel and strengthening their internal legal capacity. Firms that work closely with U.S. professionals and employ managers with U.S. training or international experience tend to adapt far more effectively. Lenovo, for instance, has undergone extensive institutional adaptation. Its general counsel is an experienced U.S. lawyer, and compared with many other Chinese multinationals, the company has navigated the U.S. legal system and an increasingly complex geopolitical environment with considerable skill.

AL: What were some interesting patterns or trends that you noticed during your research?

JL: One important area of focus in my research is ownership structure—specifically, whether state-owned multinationals behave differently from privately owned Chinese companies. In several important respects, they do. For instance, state-owned enterprises are more likely to dispatch managers from headquarters to the United States to oversee legal matters, rather than hiring in-house counsel locally.

Some do so to satisfy the requirements of Chinese regulators for the protection of state assets. By contrast, privately owned Chinese companies typically approach decisions regarding internal legal capacity through a cost–benefit lens. There are, of course, exceptions. TikTok is a prominent example. Although privately owned, the company’s high profile and strategic importance mean that its fate is shaped by both the U.S. and Chinese governments.

A key takeaway from the book is the complexity of the landscape. A range of corporate factors (e.g., ownership structure, firm size, investment duration), sectoral factors (e.g., regulatory intensity), and institutional factors (e.g., the availability of remedies such as diplomatic assistance) may shape Chinese multinationals’ legal experiences in the United States.

A notable pattern is the dual-institutional influence on Chinese companies’ dispute resolution behavior. Chinese managers carry home-state cognitive and normative frameworks with them, which in turn influence their litigation strategies in the U.S. context. My research reveals considerable reluctance to escalate disputes—not only because litigation is expensive, but also due to concerns about reputational damage, a factor that weighs far less heavily on their U.S. counterparts.

AL: You discussed how Chinese SOEs (state-owned enterprises) and private companies differ in their approach to U.S. legal risks. What differences and similarities do they exhibit, and what significance does it hold?

JL: These two types of business associations interact with the U.S. legal system in distinct ways. While private firms are primarily profit-driven, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) do not always prioritize profit maximization. For example, Chinese SOEs often emphasize corporate social responsibility. Put differently, privately owned Chinese firms tend to embrace shareholder primacy, reflecting mainstream U.S. corporate governance norms, whereas SOEs are more inclined toward stakeholder-oriented models, closer to those found in continental Europe and Japan.

SOEs also face more complex agency problems. Because they are ultimately owned by the state rather than individual shareholders, their governance often reflects bureaucratic logics. Managers at SOEs tend to be more risk averse, as their compensation is less directly tied to firm performance, and they typically enjoy greater job security than their counterparts in the private sector. This risk aversion is critical to understanding their preferences and behavior in U.S. dispute resolution.

Moreover, the current U.S.–China geopolitical rivalry has amplified trust deficits toward Chinese SOEs. To mitigate this, they are more likely to retain U.S. lawyers with government backgrounds. Such intermediaries, trusted by U.S. regulators and familiar with the inner workings of government agencies, help bridge informational and institutional gaps.

Finally, SOEs also diverge from private firms in litigation patterns. My research shows that they are significantly more likely to be sued in U.S. federal courts, underscoring their heightened exposure and the distinctive legal environment they face.

AL: Can you elaborate on that a bit? Why are SOEs more likely to be sued?

JL: My explanation is that agency problems make state-owned enterprises less efficient in resolving disputes. When a dispute arises, decision-making is often delayed because managers tend to wait for instructions from their superiors, who, being risk averse, may in turn defer to higher-level authorities. This hierarchical process often leads to escalation rather than early resolution.

Local managers may also fear that settling a case could raise suspicions or be interpreted as admitting fault. Litigation, by contrast, is perceived as more transparent, allowing blame to be more clearly allocated. If managers believe they are not personally responsible for the underlying issues, they are often inclined to litigate rather than settle—even though settlement is typically less costly in the U.S. context and often preferred. As lawyers often put it, “you pay the jerk to walk away.”

In the current political environment, Chinese state-owned enterprises are also especially vulnerable as litigation targets. Their high profile makes them more visible to potential plaintiffs, and unlike private firms that sometimes engage in “China-washing,” SOEs cannot fully obscure their Chinese and state-owned background.

As a result of these factors, Chinese SOEs are sued more frequently in U.S. federal courts, even when controlling for factors such as firm size, regulatory exposure, and investment duration.

AL: You mention that a minority of Chinese investors still adhere to home-state norms, preferring settlement over litigation to avoid reputational damage. If I understand correctly, you suggest that this preference may sometimes do them more harm than good. Could you elaborate?

JL: In the U.S. context, a strong preference for settlement sometimes signals that a legal case is weak. This interpretation shapes strategic behavior: once the opposing U.S. party perceives a strong willingness to settle, it often infers weakness and responds more aggressively—by demanding more in settlement or insisting on litigation.

This dynamic often works against Chinese companies during settlement negotiations. In China, expressing a willingness to settle is generally interpreted as a gesture of goodwill, encouraging reciprocal compromise and a middle-ground resolution. By contrast, U.S. parties without such cultural knowledge tend to interpret such offers as strategic weakness. This divergence leads to unintended consequences for Chinese companies that continue to approach disputes under Chinese social norms.

AL: That’s really interesting. Building on that, are there any other cultural or institutional gaps that prevent Chinese investors from making informed legal decisions in the U.S.?

JL: The U.S. legal system is both complex and markedly different from China’s. Chinese managers often lack sufficient knowledge to accurately assess legal risks in this environment and tend to underestimate those risks. This problem is compounded by the rigid hierarchical control many Chinese companies exercise over their foreign affiliates. Litigation decisions are frequently made by headquarters in China, where decision-makers often lack the necessary understanding of U.S. legal institutions to make well-informed choices.

In addition, the role of lawyers differs significantly between the two countries. In the United States, legal counsel plays a central role in business operations, whereas in China their role is more limited. U.S. legal complexity requires competent counsel, but institutional and cultural gaps often create trust issues between Chinese managers and their American lawyers. When Chinese multinationals distrust or disregard their lawyers’ advice, their legal strategies become less effective and dispute resolution less efficient.

AL: Can you name a few examples like this, how Chinese preferred settlement over litigation? Are there any other Chinese enterprises’ legal preferences, so to speak?

JL: For a long time, Huawei avoided litigation against the U.S. government. Their reluctance to sue had multiple causes, and as noted earlier, a key takeaway from the book is that Chinese companies’ legal strategies are highly diverse, making oversimplification misleading. One major factor, in my view, was the fear expressed by decision-makers at Huawei’s headquarters of potential U.S. government retaliation. This concern was likely overstated—at least before the Trump administration’s trade war with China.

If the company had pursued litigation earlier and relied more extensively on U.S. legal counsel when it first became the target of growing anti-China scrutiny, it might have prevailed in some cases. Of course, to what extent litigation could have altered the broader geopolitical tensions between the two countries—or changed the trajectory of Huawei’s U.S. operations—remains an open question.

AL: Let’s circle back to the Huawei case, as it was a huge deal some years ago. Can you give us a quick rundown of what happened, and what can we learn from it? Additionally, have other companies like Huawei come up with coping strategies to address mistreatment from American authorities?

JL: Years ago, Huawei attempted to acquire two small U.S. companies, 3Com and 3Leaf Systems, but the U.S. government decided to block the transactions. Huawei considered challenging the decisions but ultimately refrained, fearing high publicity and political retaliation. Once a company becomes a target of U.S. politicians—particularly China hawks—the likelihood of meaningfully reducing that risk through litigation against the U.S. government is slim.

Chinese firms adopt different coping strategies in response to such political and regulatory risks. These strategies can be broadly divided into market and nonmarket strategies. For companies with limited U.S. exposure, the most effective option is often to exit or downsize their operations, as the geopolitical risks outweigh the potential returns. Some firms shift investment to less sensitive sectors to reduce exposure. These approaches reflect the diversity of Chinese companies’ strategic responses to U.S. political and regulatory pressures.

For firms with substantial U.S. operations, however, withdrawal or major downsizing carries significant costs. These companies often adopt alternative strategies: staying under the radar to avoid political attention, lobbying the U.S. government directly or through local partners, and, in some cases, seeking diplomatic support. In the current geopolitical climate, however, overt appeals to the Chinese government are likely to backfire, so diplomatic channels are usually a last resort. Under these circumstances, litigation emerges as a comparatively accessible and effective tool for Chinese firms to seek remedies when they believe they have been treated unfairly by the U.S. government.

AL: And how do they keep a low profile?

JL: As noted earlier, it is relatively easy for private companies to downplay their Chinese identity. A quick look at their websites often reveals no obvious indication of Chinese ownership. Many privately owned Chinese firms are highly adaptive: some have already relocated their headquarters to and reincorporated in jurisdictions such as Singapore or Switzerland. Legally speaking, they are no longer Chinese companies. However, as the TikTok case illustrates, adopting a non-Chinese legal identity does not necessarily shield a multinational from becoming entangled in the geopolitical rivalry between the two superpowers.

Such corporate maneuvers are far more feasible for private firms than for state-owned enterprises, especially larger ones. They cannot easily obscure their Chinese background or relocate their headquarters abroad, making them far more visible targets in the current geopolitical climate.

AL: How does the Chinese political and legal environment influence multinational decision-making in the US?

JL: Chinese companies increasingly find themselves caught in the middle of the U.S.–China geopolitical rivalry—truly between a rock and a hard place. When U.S. and Chinese laws conflict, firms—especially state-owned enterprises—are forced to make difficult strategic decisions. A prominent example is the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act (HFCAA), which requires Chinese companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges to allow the PCAOB (Public Company Accounting Oversight Board) to inspect their audit papers. This requirement conflicts with several Chinese laws. Although the two governments eventually reached a compromise allowing inspections in Hong Kong, many state-owned firms still chose to delist from U.S. exchanges.

This illustrates the broader dilemma: when legal obligations in the two countries diverge, companies must either make strategic trade-offs or, if sufficiently powerful, attempt to shape or navigate the legal environment. For example, when the U.S. government-imposed export controls on certain products to China, some major multinationals successfully lobbied for exemptions—gaining a competitive advantage over rivals still subject to those restrictions.

As U.S.–China confrontation increasingly takes on a legal dimension, multinationals exposed to both markets face mounting compliance pressures. Those with the greatest exposure and influence have strong incentives to stabilize bilateral relations and often find themselves on the front lines pushing back against foreign policy hardliners in both countries.

AL: In your research, you summarized that Chinese companies’ litigation experiences are largely reactive, often appearing as defendants rather than plaintiffs. What are some common causes or shared themes in these cases?

JL: Corporations are far more likely to appear in court as defendants than as plaintiffs, and Chinese firms in the United States are no exception. Their perceived financial capacity makes them attractive targets for litigation, a dynamic that is well documented in studies of corporate legal exposure. This tendency is reinforced by the litigation posture of many Chinese firms themselves. As noted earlier, some Chinese managers exhibit a strong reluctance to initiate lawsuits, either because of unfamiliarity with the U.S. legal system or cultural preferences for negotiation and settlement. This defensive orientation makes these companies less likely to be plaintiffs but may inadvertently embolden other parties to sue them.

The types of lawsuits involving Chinese companies vary considerably by sector, firm size, and business model. Technology firms are frequently involved in intellectual property disputes, reflecting the innovation-driven and competitive nature of that sector. Manufacturing companies are often drawn into labor and employment litigation, including wage-and-hour and workplace safety claims. Firms in consumer-facing industries are more likely to face tort actions, including product liability and personal injury cases. Larger and more visible companies, especially those with substantial U.S. operations, also face heightened exposure to commercial and regulatory litigation, including class actions.

AL: Looking into the future, are there emerging trends you see in how Chinese companies will engage with the U.S. legal system in the next 5–10 years?

JL: Chinese companies—particularly privately owned firms—tend to be highly adaptive. They learn from experience and make conscious efforts to avoid repeating past mistakes. Over time, Chinese investors are likely to become more sophisticated in navigating the U.S. legal system. The outlook is less certain for state-owned enterprises. Because of agency problems and bureaucratic decision-making structures, these firms often struggle to learn effectively from prior encounters with litigation, making them more prone to repeating errors.

Of course, much of what happens in court will ultimately depend on the broader political climate and the trajectory of U.S.–China relations over the next five to ten years. It’s difficult to predict how this will unfold. Nevertheless, it is clearly in both countries’ interest to find ways to manage their differences and coexist.

AL: What lessons from your research could apply to other Chinese multinationals operating in complex U.S. legal environments? On the other hand, what can your research teach American legal service providers? How can law firms and lawyers adapt to the needs of overseas Chinese companies?

JL: They need to hire lawyers with a solid understanding of China. Without a grasp of Chinese multinationals’ institutional backgrounds, U.S. lawyers may not appreciate why their clients often cannot ask certain questions directly or why decision-making processes tend to be slower and more hierarchical. At the same time, because Chinese clients generally contribute only a small share of revenue, many large U.S. law firms treat them as “second-class” clients, offering less tailored service.

Chinese multinationals may receive better support from mid-sized firms, which are often more flexible and responsive. U.S. firms seeking to expand their China-related practice could consider adopting more flexible fee arrangements, highlighting attorneys with U.S. government backgrounds, and hiring lawyers with Chinese language skills and cultural expertise to better serve these clients.

AL: What about from the other side? How can Chinese multinationals better operate?

JL: Chinese companies should employ competent in-house counsel who can effectively interact with U.S. lawyers and navigate the U.S. court system. Ideally, this counsel should also possess a strong understanding of the company itself. The ideal in-house lawyer for a Chinese multinational is someone with deep knowledge of the Chinese business and legal environment, U.S. legal education, and several years of legal practice experience in the United States.

Just as important, the company must trust this in-house counsel and rely on their professional judgment. Because the pool of such talent is limited, Chinese companies should be prepared to offer competitive compensation to attract and retain qualified candidates.

AL: Can you give us a rundown of what role in-house counsels play, and how they collaborate with external lawyers to help?

JL: In-house counsel plays a critical role. With a deep understanding of a company’s operations, they are well positioned to assess legal risks, evaluate external counsel, and help procure effective legal services. The U.S. legal profession is both large and highly developed, with more than 1.2 million lawyers nationwide. Faced with such an extensive pool of options, selecting the right legal representation is no easy task.

Someone who understands the U.S. legal market is essential for making informed hiring decisions, and in-house lawyers are crucial in this regard. Without their guidance, Chinese investors are effectively navigating the U.S. legal landscape in the dark. They may struggle to identify trustworthy and qualified lawyers with the appropriate expertise, and they may struggle to assess whether legal costs are reasonable.

AL: America has a very vibrant law industry, whereas in China law seems to assume quite a secondary, less important role. How can we account for this?

JL: China’s economic development over the past four decades has been a process of creative destruction of institutions inherited from a Soviet-style planned economy. This trajectory fostered a mindset that prioritizes rapid development over legal formalism and often downplays the role of law. In the United States, by contrast, the market system is deeply grounded in law. It is not uncommon for Chinese businesspeople to agree on substantial transactions without consulting legal counsel or conducting thorough due diligence. In the U.S., however, it is widely understood that doing business necessarily involves legal compliance and risk management.

These contrasting practices reflect two fundamentally different corporate cultures. Chinese managers shaped by China’s reform-era mindset often underestimate legal risks when entering the U.S. market, which frequently causes difficulties, particularly in the early stages of their investments.

AL: You spoke about how U.S. companies frequently find Chinese companies’ decisions very unexpected, surprising a bit. Can you give one example that stands out most to you?

JL: American parties often complain about unexpected delays in decision-making. Negotiations may seem to be progressing smoothly, only for the Chinese headquarters to reject the deal at the last minute. This pattern is particularly common among Chinese state-owned enterprises. In one illustrative case, a U.S. lawyer provided a standard risk assessment as part of the due diligence process. Although the opinion was routine, the Chinese SOE’s headquarters ultimately shelved the deal, unwilling to tolerate any level of risk.

This episode reflects the fundamentally different ways in which the two sides approach business risk disclosure. The U.S. approach emphasizes full disclosure and typically errs on the side of caution. Chinese managers, however, often struggle to interpret and weigh these disclosed risks, leading them to abandon transactions altogether.

AL: What would you educate an ordinary American business owner about Chinese businesses and their legal decision-making propensities?

JL: As I’ve emphasized throughout, one key takeaway from my book is that corporate decision-making in this context is nuanced, complex, and highly contingent on specific circumstances. Outcomes are best understood through a case-by-case analysis. When dealing with Chinese state-owned enterprises, American counterparts should expect slower decision-making and be prepared for choices that may appear irrational from a U.S. perspective.

When working with privately owned Chinese companies, surprises are also common—though for different reasons. These firms often lack a deep understanding of the U.S. legal system, which can lead to serious miscommunications. My strongest advice to American companies is to encourage their Chinese counterparts to bring a trusted lawyer to the negotiation table as early as possible. Ideally, someone with knowledge of both the Chinese and U.S. legal environments. Doing so can help prevent misunderstandings and build a more stable foundation for negotiation and cooperation.

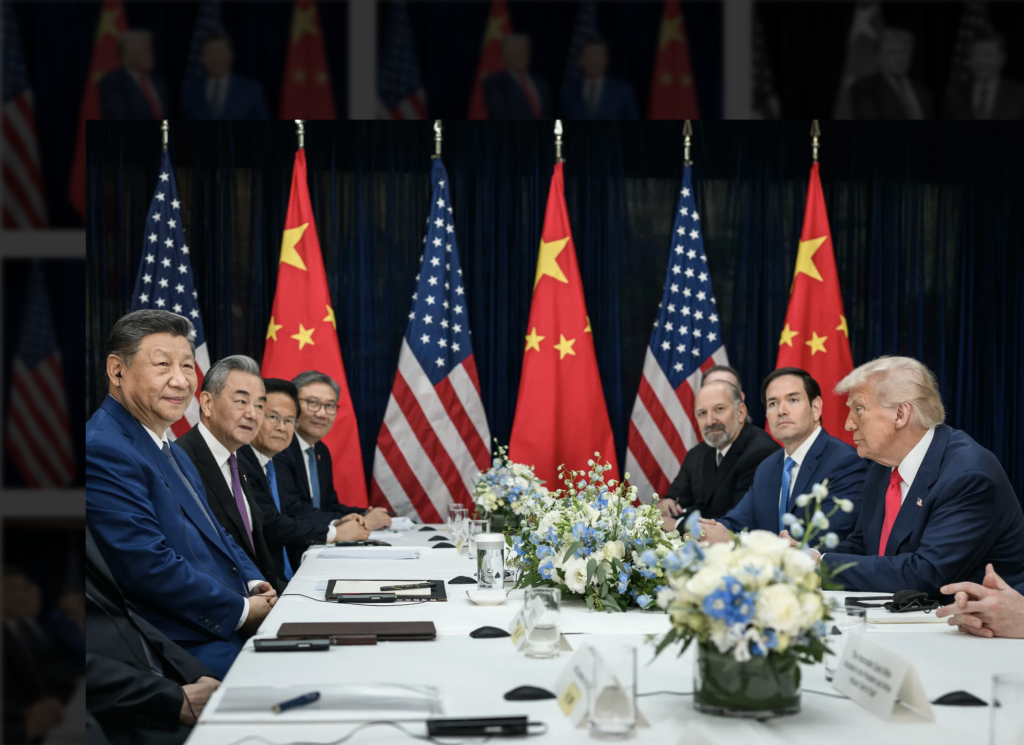

AL: How do global events, such as Trump’s trade war and the resulting U.S.–China superpower rivalry, affect Chinese companies’ legal experiences in the U.S.?

JL: Chinese companies are under immense pressure to maintain a low profile amid heightened political scrutiny. Compounding this challenge, U.S. laws and policies are changing rapidly. As a result, these firms now face significantly elevated legal and regulatory risks in the United States. To navigate this increasingly complex geopolitical environment, they must rely more heavily on experienced legal counsel.

AL: And what are some of the emerging demands or expectations that Chinese companies have of their lawyers?

JL: There has been a decline in demand for corporate services from Chinese companies as a result of U.S.–China economic decoupling. At the same time, however, their demand for compliance and litigation services appears to be increasing. In particular, many firms—especially those operating in more sensitive sectors—require ongoing legal advice to navigate rapidly evolving export control regulations and sanctions regimes.

Author

-

Alice Liu is an intern for China Focus at The Carter Center and studies History and Women’s Studies at Emory University.