An Interview with Pascale Massot on Power, Vulnerability, and Market Disruption

- Interviews

Alice Liu

Alice Liu- 10/28/2025

- 0

Xi’an, Shanxi, China. Source.

Over the past two decades of China’s surging economic transformation, many unexpected phenomena emerged. Canadian scholar Pascale Massot turns her attention to China’s critical mineral market, seeking to explain several paradoxes: why, despite being the world’s largest buyer, Chinese market participants have historically felt vulnerable and constrained by structural factors; and why a state-led, hybrid capitalist system like China’s has paradoxically led to liberalization and financialization dynamics in the global iron ore market starting in the 2010s.

Dr. Massot builds her analysis around the concept of coordination capacity, revealing that the roots of China’s variation in global market behaviors lie in the variation in fragmentation among its domestic stakeholders across case studies—the misalignment between government agencies, industry associations, and enterprises that has at times prevented China from translating its enormous economic scale into effective market power.

Pascale Massot is an associate professor in the School of Political Studies at the University of Ottawa. She served as the Senior Advisor for China and Asia in the offices of various Canadian Cabinet ministers, including the Minister of Foreign Affairs and the Minister of International Trade. Her book, China’s Vulnerability Paradox: How the World’s Largest Consumer Transformed Global Commodity Markets (Oxford University Press, 2024), is Winner of the 2025 Best Book Award in International Political Economy from the International Studies Association and 2025 Peter Katzenstein Book Prize.

Today, Alice Liu speaks with Massot about China’s Vulnerability Paradox to better understand the political economy of China’s commodity markets, and its international behavior . A close study of Chinese mineral markets can provide insight into some of the nation’s economic problems. Dr. Massot made the insightful remark that China’s and the US’s political and economic problems can mirror one another, a valuable perspective for academics and decision-makers alike.

Alice Liu: Last year, you published China’s Vulnerability Paradox, a book examining China’s impact on the global political economy of commodity markets. Could you briefly introduce the book for our readers?

Pascale Massot: The book addresses three puzzles. The first puzzle is the variation in China’s impact on global markets over the past couple of decades. In the early 2010s, when I looked at various commodity markets for iron ore, potash, uranium, and copper, I observed different kinds of impacts from Chinese stakeholders. China had become the largest consumer of all those commodities in the 2000s, yet its impact varied across global markets.

The second puzzle is what I call in the book “the vulnerability puzzle.” Despite China’s immense market size, I found that Chinese stakeholders felt more vulnerable than powerful. That piqued my curiosity — how can it be that the largest actor in the market feels so precarious?

The third puzzle I tried to tackle is that China’s rise as number one consumer of iron ore had a liberalizing and financializing impact on the global iron ore pricing regime in the 2010s. That was both puzzling and intriguing. How could China, a state-led, hybrid capitalist economy, drive the financialization and liberalization of a global market?

AL: What is the core argument of your book then?

PM: I argue in the book that relative positions of market power between Chinese and international market stakeholders help explain the variation we see in China’s behavior internationally, as well as the likelihood of institutional change globally.

I conceptualize markets as created rather than spontaneous, embedded rather than autonomous, and disputed rather than self-adjusting. I also see markets as plural, not homogeneous. Those four characteristics of markets are important propositions on which I build my argument and conceptualize the notion of global market change.

I analyze the differential positions of market power between Chinese and global market players. In the book, I use coordination capacity as a proxy for market power. Various Chinese stakeholders—firms, industry associations, the relevant government stakeholders, port authorities, etc.—sometimes coordinate effectively and sometimes fail to do so. This varied greatly across different markets in China in the 2010s.

The iron ore case was a good example of domestic fragmentation: there was little coordination between state organs and private actors, and between large and small firms, at the time of China’s rise as the dominant consumer. On the other hand, the global actors were, and still are, quite effectively coordinated. This lack of coordination capacity on China’s part was crucially important in explaining the ensuing dynamics in that market.

AL: Why is China’s ability to coordinate weak in certain industries? What are the factors behind it—for example, divisions of interest, lack of trust, or bureaucratic culture?

PM: I think if we step back, we could trace the origins of this variation to the political economy of different industries since the early days of the PRC. It remains that coordination capacity varies across cases. In the potash market, for instance, the import interface is more concentrated, and the Chinese actors coordinated effectively among themselves. A few importers consulted internally before negotiating with global exporters, creating a more symmetrical coordination capacity between Chinese and global stakeholders.

I look across markets at how these differential positions of market power play out. My ultimate argument is twofold. First, dominant positions of market power afford the dominant stakeholder more leeway in influencing global market institutions. Secondly, change in global market institutions is more likely to occur when the emergence of a new player is disruptive to established market power relations.

AL: You repeatedly describe this paradox—that China is simultaneously the largest player in the market and the most vulnerable one. Can you explain, in simple terms, what this vulnerability looks like in practice? In what specific aspects is the Chinese economy vulnerable?

PM: I did not set out to investigate this vulnerability paradox, but it was so fascinating that I ended up making it part of the book title. It’s something that became clear to me when I was conducting my interviews in China in the early 2010s. I think it remains relevant today, as the common Western perception is that China dominates all aspects of critical minerals markets, which is not accurate. When I conducted interviews in China, I was repeatedly told by market stakeholders that China’s size didn’t necessarily provide it with a strong hand to influence global markets. Instead, the country found itself in a position of weakness.

Many tend to confuse market size and market power. In fact, China is import-dependent for most of its raw commodity imports—in all the cases I study in the book, copper, iron ore, uranium, and potash, it imports close to or over 50% of its needs.

A second way in which the vulnerability paradox manifested is that China’s rise in commodity consumption at the turn of the century was just too fast for global markets to handle. A commodity super cycle occurred in the lead up to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, largely driven by China’s rapid rise. China’s consumption grew at a pace the global mining industry was not prepared for. This led to huge price volatility in the 2010s, which was also a source of insecurity for China.

The third way in which China’s vulnerability manifested is through its status as a relative latecomer to large-scale commodity consumption. In other cases, like in some tech areas, this latecomer status can actually be an advantage. But in the case of commodities procurement, when China was acquiring mining assets globally in the 2000s and 2010s, the best, most accessible, and most economically viable deposits were often already taken. China found itself venturing into less stable polities and developing more challenging deposits — such as the Simandou iron ore project in Guinea. After more than 25 years of setbacks, the project may finally see its first shipment later this year.

Finally, China’s precarity lied in the market power differential Chinese stakeholders experienced in relation to global market players. In some cases, China’s importers were in a position of weakness compared to powerful, concentrated, and coordinated global mining giants. We must remember that in some of these industries, such as iron ore, the export market is controlled by three or four enormous firms. The iron ore market is controlled by BHP, Rio Tinto, Vale from Brazil, and Fortescue, to the tune of over 75% of the global export market.

AL: Do you see this vulnerability as a temporary phenomenon or is it something that could become a long-term feature of China’s economic structure?

PM: Interesting question. I think that it will continue to evolve. In today’s context, China’s export restrictions and licensing system on rare earth minerals, materials, technologies, and related magnets are top of mind. The position of dominance that China was able to build in these areas, I would argue, is very much the result of a deep, historical feeling of insecurity over resources procurement. China has felt very vulnerable on this front from the very beginning of the PRC, all the way from food to base metals and materials.

Ever since, the drive towards self-sufficiency has been a recurring theme. Authorities devoted a lot of energy to thinking about domestic and international dimensions of procurement security much more deeply and assiduously than we have in the West. This has resulted in more fully fleshed out domestic and international procurement strategies being rolled out around the world, or implemented in China over the past decades (from domestic exploration to the leveraging of the whole value chain), whereas in the West, until very recently, the tendency was to look at resource security through the lens of market-driven solutions.

However, I think it is important that we also look at China’s remaining challenges on this front. It has been able to build positions of strength in certain supply and value chains of minerals, metals, and materials, but by no means uniformly. Upstream, as I alluded to earlier, there are some geological limits to what China can achieve. Whereas it has been able to build positions of strength, especially in the refining, processing, and manufacturing segments, it does remain dependent on imports at the very upstream segments of most value chains.

China’s market power varies across the value chain. At the other end, in terms of manufacturing capacity, I would make the case that China has developed vulnerabilities in export access as well. We often hear about overcapacity in the West and beyond—for instance, regarding electric vehicle exports. China has developed an industrial ecosystem that relies on access to export markets, and this has proven more politically fraught than Chinese leaders might have expected a decade ago. China is facing pushback not only in Western economies but also in countries such as Brazil, Turkey, South Africa, or Thailand, where the domestic ripples caused by the rapid growth of Chinese manufacturing exports are leading to the imposition of trade protection measures.

AL: Are there any additional cultural or political factors that give rise to this perception of market vulnerability?

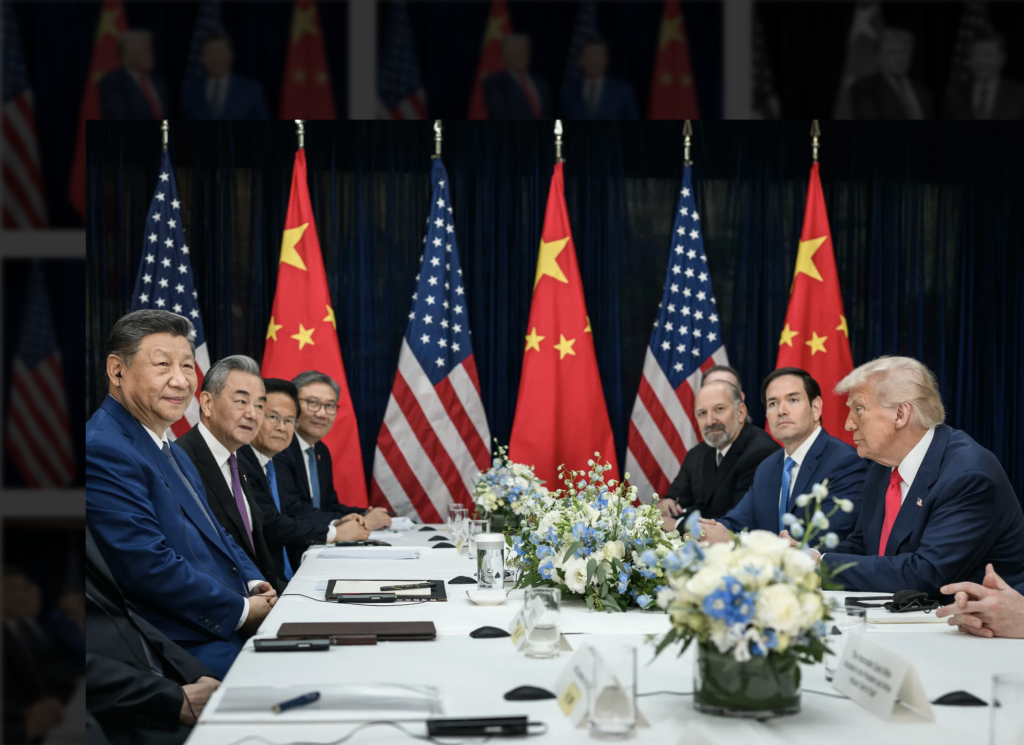

PM: I think the current external environment, for better or worse, is heightening perceptions of vulnerability in China, and feeding a negative cycle. This resembles a traditional security dilemma: actions portrayed domestically as defensive in nature are perceived by the other side as threatening. The result is increased sentiment of vulnerability on both sides. The negative cycle has intensified rapidly over the past few months. Trust is low, and both the US and China have deployed — or threatened to deploy — actions that can be quite economically damaging. China, in fact, appears to have the upper hand right now in terms of leverage over heavy rare earths and related permanent magnets.

AL: Going back to your book, why did we see such different trajectories of market change in the two cases of iron ore and potash? Was this mainly due to differences in China’s ability to coordinate or something else?

PM: What I observed in the iron ore case in 2010 was really the end of a decades-long pricing system. Iron ore prices, up to then, had been negotiated behind closed doors between Japanese buyers and global producers, chiefly the main three — Rio Tinto, BHP, and Vale. This system had led to stable prices for the 40 years before China emerged as the number one consumer of iron ore.

In 2003, China overtook Japan as number one consumer; in 2006, China took the mantle over from Japan as lead negotiator in the benchmark negotiations. But by 2010, the system had fallen apart. And what rose instead was spot pricing and increased financial volatility of iron ore pricing. This represents the transition from a strategic, negotiated pricing system to a more volatile, financialized, liberalized pricing system. Whereas in the potash case, the benchmark system has more or less survived to this day.

So, you have the survival of a pricing system in the potash case, and the breakdown of a pricing system in the iron ore case. How do I explain that? The difference can be attributed to coordination capacity, or market power, which was present in the potash case but not in the iron ore case in 2010. What’s important to note in this story is that if we looked only at the outcome— the fall of the benchmark—and inferred Chinese actors’ intentions solely from it, we would reach the wrong conclusion.

This outcome was both unintended and unanticipated by lead Chinese stakeholders, state actors, and the large state-owned enterprises that were active at the time. Both of those groups would have preferred a continuation of the benchmarking system. They did not want the benchmarking system to collapse. It was really the result of a coordination failure on behalf of China.

As a result of what can only have been an assessment of this failure to coordinate, the Chinese government established the Chinese Mineral Resources Group in 2022. 15 years after the fall of the benchmark, this group is explicitly tasked with trying to coordinate iron ore purchases, and to translate China’s market size (it imports over 70% of global iron ore imports) into a position of market power. This demonstrates that the Chinese government is very much aware of this coordination failure and is working hard to address this problem. And we have seen in the news just this past couple of weeks that this group is indeed negotiating in a very tough way to try to achieve some pricing power and has asked Chinese iron ore importers not to import iron ore from BHP while the negotiations are ongoing.

AL: Let’s come back to this question of Chinese stakeholders: despite their growing power, they are often unable to shape markets in their preferred direction. Aside from Chinese economy’s import-dependent nature, what other factors contribute to this paradox?

PM: I have touched on the four ways in which China displays vulnerability in its relationship with global markets. I’ve been trying to reflect more broadly about the relationship between sentiments of vulnerability and behavioral tendencies. Many assume that a rise in power, the increase in power of a rising state, would increase the likelihood of disruptive behavior. In other words, that sentiments of vulnerability lead to more conciliatory behavior, while greater national strength leads to assertiveness.

I think the relationship between power or vulnerability and disruption is not so straightforward. Other scholars have tried to complicate this. Robert Keohane argued in 1989 that states did not seek to maximize power at all times, but only when they feel endangered. He argued that “states moderate their efforts when their positions are secure”, and conversely, “intensify their efforts when danger arises”. Others, such as Yves Tiberghien, have argued that China may in fact be more likely to act in a disruptive fashion in situations where it has either limited room for maneuver or is facing threatening actions internationally.

This is an argument that echoes Taylor Fravel, in his 2008 book, Strong Borders, Secure Nations. He argued that China may be more likely to be assertive in the context of border disputes when it feels threatened by another large power and that it may be more likely to compromise in moments of domestic insecurity. I cover these debates in my book. All this to say that I don’t think there is a consensus in the literature about the relationship between perceptions of vulnerability and external assertiveness. In my cases, I find that perceptions of market power have resulted in a range of behaviors, including more status-quo behavior, which means that at a minimum, more confidence or room for maneuver does not necessarily lead to assertive or disruptive behaviour.

AL: On a broader scale, what do your findings tell us about China’s role as a global economic power? What lessons can we take away from this study, in thinking about China, US–China relations, and the world?

PM: First, we should really take into consideration the role of unintended and unanticipated consequences. I think this is particularly important now. When it comes, for example, to some of the actions that the US has taken in terms of trying to limit technological advances by China over the past few years… Let’s put it this way: it remains to be seen whether or to what extent that was destructive in the long run—not only to the US position or US–China relations, but also in terms of global public goods. In today’s context, when uncertainty is very high, attention to possible unintended, second-order consequences should be part and parcel of how we think about China policy.

Second, we should not assume intention by looking at outcomes. My book allows us to think about the variation in China’s behavior across cases and trying to understand their domestic roots. Too often, there may be a tendency to derive China’s intentions from its international behavior or impact. When doing so, we can come to erroneous conclusions. Process-tracing, and the unpacking of the domestic dynamics that lead to certain decisions, remain an important antidote to simplistic arguments about China’s international ambitions.

If I hadn’t tried, for example, to process-trace the story of the fall of the iron ore benchmarking regime, I wouldn’t have understood the lack of coordination capacity. I might have assumed it was the intention of Chinese actors to bring about this institutional change. Similarly, in the potash case, I wouldn’t have understood how important the successful coordination of China’s procurement behavior was in explaining international outcomes. So, I think that it’s crucial to try to understand the domestic context in explaining variation in China’s behavior internationally. We should also acknowledge—and this applies to the United States as well—that very often, even in terms of international behavior, domestic considerations are key.

AL: And how do domestic considerations shed light on the dynamics of global commodity markets?

PM: My book also urges people to think about market power more seriously. Only very recently have we started (again) to think more systematically about economic security and market power in the West, pretty much since the COVID pandemic. Considering power dynamics in global markets is essential. I would go even further, and this is where I come in when I discuss the liberalization puzzle: we must think very transparently about market openness, what it is, what we are trying to preserve, and how exactly is that openness threatened internationally.

What does liberal market openness mean? How do we think about power relations between large and smaller firms, and industrialized and developing countries? Without unpacking these questions, we won’t be able to arrive at a renewed call for economic globalization that will be appealing both for industrialized countries and for countries around the world.

Lastly, the book really adopts an interactive view of China and global economic dynamics. I came to realize through writing the book that there are deep resonance dynamics between China and the US, and China and the global economy. Domestic economic decisions in China can now have a significant impact on economic dynamics in countries around the world. But at another level, the deep challenges that both China and the US are facing domestically—have interesting resonance dynamics as well. Perceptions of vulnerability are made worse by each country’s own domestic challenges and are reinforcing these dynamics.

Looking back 30 years, I think we can trace some of the roots of the political and economic challenges that the US is facing in terms of the crisis of hyper-globalization and openness of trade, and that China is facing in terms of overcapacity and other domestic economic challenges to each other’s economies. China’s entry into the WTO and in the global economy, as well as other economic and technological disruptions, have caused ripple effects that the US has not been able to deal with adequately domestically, in part because of an ideological aversion to some types of state involvement in its economy.

These disruptions have had profound political impacts. We now see a resurgence of economic nationalism and government involvement in the US economy, approaches that many had long accused China of abusing. I find this profoundly interesting. There are deep resonance dynamics between China and the US, and China and the global economy, which we would do well to unpack further.

Author

-

Alice Liu is an intern for China Focus at The Carter Center and studies History and Women’s Studies at Emory University.