Interview with James Siebens on Taiwan and China’s Strategy

- Interviews

Tyler Quillen

Tyler Quillen- 11/04/2025

- 0

Over the past 20 years, China’s “peaceful rise” has included substantial investments in military modernization, coupled with an increasingly assertive regional posture. While China has not waged war in several decades, in recent years it has frequently resorted to what the U.S. State Department previously referred to as “gangster tactics” – threats, intimidation, and armed confrontation – to advance its strategic aims. China generally presents its “demonstrative uses of force” as defensive, often claiming that it is acting in response to provocations from other states. However, China has increasingly used military and paramilitary forces to improve its position in long-standing disputes with other countries, and to strengthen deterrence and coercive pressure targeting the U.S. and Taiwan, for example. This trend is perhaps most evident in China’s persistent “gray-zone” activity surrounding Taiwan.

In China’s Use of Armed Coercion: To Win Without Fighting (Routledge 2023), Siebens and colleagues present a thorough study of China’s efforts to use armed coercion in recent decades. This book illuminates the ways in which China has employed military and paramilitary tools to coerce other states using force short of war, and examines its motivations and specific foreign policy objectives. The book also presents a series of case studies focused on China’s use of coercive diplomacy and military signaling from the Korean War to the present day, including recent campaigns targeting Taiwan, Japan, the South China Sea, the United States, and India.

Drawing in part on lessons from this work, Siebens partnered with Stimson colleagues Dan Grazier and MacKenna Rawlins to unpack the nature of the threat China poses to Taiwan, producing a report entitled “Rethinking the Threat: Why China is Unlikely to Invade Taiwan” in which they argue that China has many compelling reasons to avoid the scenario of a full scale invasion, and is much more likely to prefer unification through other means, including political warfare and coercion.

James Siebens is a Fellow with Stimson Center’s Strategic Foresight Hub, where he leads the Defense Strategy and Planning project focused on grand strategy, coercion, and gray zone conflict. Siebens is the editor of China’s Use of Armed Coercion: To Win Without Fighting (Routledge 2024), and co-editor of Military Coercion and U.S. Foreign Policy: The Use of Force Short of War (Routledge 2020), a book on U.S. deterrence and coercive diplomacy since the end of the Cold War. He is also a Term Member at the Council on Foreign Relations and a Non-resident Fellow with the Irregular Warfare Initiative. Tyler Quillen sat down with Mr. Siebens on October 3, 2025, for an interview discussing his recent work’s findings regarding possible futures for cross-strait relations, the nature of Chinese coercion, and what nations can learn from both.

Tyler Quillen: To begin, where does the Chinese public stand on a Taiwan invasion? In an authoritarian context, does public opinion matter?

James Siebens: I think public opinion always matters because governments are just about always dependent on public acquiescence, if not consent. We saw recently in Nepal what it looks like, or what it can look like, when a government completely loses the consent of the governed. So, I think that perhaps especially in an authoritarian context, that’s something that governments have to be concerned with. In a democracy, we have the ability of kind of letting off steam every couple of years in elections, and we can imagine ourselves as having influence on policy menus at least, and maybe just in an indirect way, but there is this notion that we have influence on the policies that the government engages in. That is far less plausible or less believable in an authoritarian context. And so, the government is more dependent on things like economic performance or social tranquility for its legitimacy.

Now, in the context of starting a war, that’s something that would predictably disrupt domestic tranquility and harmony among Chinese people, especially if you think of Taiwan as a part of China, as the P.R.C. does. So, they have a kind of social aversion to the idea of starting a war with other Chinese people. If the government in Beijing was contemplating starting a war, they would certainly have to grapple with the fact that it could be unpopular and could disrupt the domestic tranquility that they prize. It would also undercut the idea that they view the people on the other side of the Taiwan Strait as compatriots, as fellow Chinese people with whom they would like to have harmonious relations in principle. But that is conditional, and I think there’s a strong nationalist impulse in China to unify the country as they would see it. In fact, a couple years ago, a public opinion survey that was conducted found that a slim majority of the Chinese respondents actually did support the idea of forced unification. However, that survey also found that respondents didn’t support that idea more than they supported a whole range of less aggressive options, including more limited military moves as coercive pressure, the likes of which we are currently seeing and can easily imagine growing, like economic pressure, especially in the form of trade barriers and that sort of thing. So, let’s say popular sentiment is a factor and if anything, it’s a factor that appears to support the P.R.C.’s effort to bring about unification, whether the people of Taiwan want it or not. At the same time, it is not a strong source of pressure to go to war against Taiwan.

TQ: Recent reporting on Washington’s strategies in the Indo-Pacific bring U.S. commitments to Taiwan into question. Do you think this matters to Beijing? How?

JS: Yeah, I think it matters politically and diplomatically, for sure. On the one hand, we have some indication that the Trump administration is prioritizing engaging in direct dialogue with Xi Jinping and that he would therefore be unlikely to deliberately undermine the potential for that kind of engagement by doing anything that Beijing would predictably be mad about vis-a-vis U.S. policy toward Taiwan. So, at least for the time being, that indicates Beijing may want to leverage the desire for negotiations on the part of the U.S. as a way of bringing the Taiwan issue to the table alongside other issues of importance like trade, international cooperation on combating narcotics trafficking, and issues like Ukraine perhaps. There are a variety of issues that’ll be on the table in a broad negotiation between the U.S. and China, and Taiwan is an issue that China will almost certainly attempt to extract concessions on. Further, I think Beijing is always willing and ready to drive any available wedges between Washington and Taipei. And I have it on good authority that narratives to the effect that America may at some point abandon Taiwan are very touchy and very divisive in Taiwan. So, just the discussion in a public context about that risk where the U.S. and China are having bilateral dialogue and negotiation is bound to make folks in Taipei a little bit nervous.

Now, in your question, you used the phrase U.S. commitments to Taiwan, so I think it’s worth unpacking that a little bit. The United States does not have a treaty obligation to defend Taiwan, as I’m sure you know. But U.S. law does require that the U.S. maintains the capacity to resist the P.R.C.’s efforts to conquer or coerce Taiwan. But that doesn’t necessarily require the president do anything, right? It’s just a requirement to maintain the capacity. The actual policy about whether or not, or the extent to which the U.S. might intervene in any of the variety of Taiwan scenarios that I think we’ll talk about more, that is a decision that is left up to whoever is currently the U.S. president. So, we saw under President Biden a fairly clear and unequivocal stance that the U.S. would intervene, that he would order U.S. forces to intervene if the P.R.C. decided to attack Taiwan. There weren’t a lot of details around the conditions under which they would be attacked or the context, but he said in a fairly blanket way multiple times, yes, he would order the intervention of U.S. forces. President Trump has not said anything like that and in fact has said basically he knows that it’s sensitive and he should be careful about what he says. I interpret that in the context of these forthcoming negotiations with Beijing, that he understands that is a chip that he has to play with potentially, which is a uncomfortable place for folks in Taipei to be because they see the American commitment as really a fundamental aspect of their national security and their de facto autonomy.

TQ: The threat of economic fallout from an invasion of Taiwan looms large over the P.R.C. What economic challenges are most threatening to China in this scenario, and how is it likely to react? And what about the same for Taiwan and the United States?

JS: If we are talking about a scenario in which Taiwan and mainland China are fighting each other, two things become obvious right away. One, the Taiwan Strait would not be open to commercial traffic in all likelihood, and even if it were open to commercial traffic, maritime shipping would be rerouted away from the area where ships could expect delays or worse—so there would be massive disruption in global maritime commerce. China is the world’s largest exporter of goods, so that would disproportionately hurt China. Furthermore, other countries might level some forms of economic sanctions against China in response to its decision to attack Taiwan. So, I think that sanctions might be the biggest threat that the P.R.C. would be facing, and even if it was able to evade some of the consequences of those sanctions, it would certainly harm the Chinese economy in a way that couldn’t be easily ignored. As a result, we’d have the impact on China’s economy directly from economic sanctions and then just the practical impact of an active conflict in the Taiwan Strait on international shipping. Both goods to and from China would be disrupted, goods to and from Taiwan, goods to and from the United States, et cetera. No one would be spared from the economic fallout of that scenario.

Now, how would China react to deal with that circumstance? Presumably it would try to redirect trade to some of its other ports farther away in the North or South, or it could try to shift to rely more on over-land routes using rail and road systems. But, like I said, the disruption would be impossible to ignore and hard to overstate. It’s also worth emphasizing that the United States is reliant on trade with Taiwan and mainland China for certain goods, and that disruption would have not just an economic impact, but also potentially geopolitical consequences from the United States’ perspective. No good can come from that scenario.

TQ: Your article makes the interesting point that the military difficulty of a cross-Strait invasion is the least impactful factor limiting Beijing’s hand. Could you please explain why this is the case?

JS: Sure. The bulk of the report, “Rethinking the Threat: Why China is Unlikely to Invade Taiwan”, is focused on the operational challenges that any military would face if it was attempting to mount an amphibious assault on the island of Taiwan. One of my co-authors on the report, Dan Grazier, is a retired Marine and a former operational planner, and just looking at the history of operations like the sort that we would be talking about, he’s assessed that this would potentially be the most complex military operation in history. More complex than the D-Day landings in Europe and of a different scale, and also of a different level of difficulty in terms of the geographical and operational challenges. But—before we even get to the idea of how difficult it would be to land forces, establish a beachhead, then to move forces ashore and inland, and then to actually consolidate control over the major population centers and pacify the population—China would have to think about the prospect of a war with the United States, and obviously China and the United States both have nuclear weapons. Now, if you’ll recall, in 1950 and 1953 Truman and Eisenhower both insinuated that the U.S. might use nuclear weapons in the context of the Korean War. But that was also in the context of the United States using the 7th Fleet to prevent Mao’s China from continuing its campaign to take over the islands still under the control of the Republic of China and the Kuomintang government. Those nuclear threats from the 1950s have cast a long shadow over U.S.-China relations and Chinese perceptions of the risk of nuclear war with the United States and their connection to Taiwan. So, that’s one thing to just be clear about; China would regard the risk of nuclear escalation as non-zero, which would mean they’d have to think seriously about it. And even if the conflict did not escalate to nuclear war, China would need to contemplate a high-end conventional conflict with the United States, something it has no experience with whatsoever, and it has observed in great depth how the countries that do have experience with modern conventional wars against the United States don’t have very positive experiences.

Secondly, the decision to go to war over Taiwan would be a political gamble for the CCP. The P.R.C. constitution talks about unification as one of its core values or purposes, and so it is something that they are formally committed to doing. But, any war risks failure, and so there’s one line of thinking that says basically China will not attempt it unless it is virtually certain that it would succeed in the effort. That’s a pretty high bar for any kind of military campaign or operation, to say that you have a high degree of confidence that it would succeed, especially if you’re talking about something like pacifying an enormous place with nearly 24 million people. That’s not an insignificant factor. It’s a “cannot fail” kind of mission. That is a cause for reflection, and it could perhaps help explain some of the military purges we’ve seen in Chinese military leadership. We could understand these as an attempt to make sure that there is discipline from top to bottom, and that officers know their jobs well and would be able to perform under wartime conditions. That also means making sure that money goes where it’s supposed to go, that it is buying the equipment that it’s set out to buy, etc. So, there is a lot of preparation for battle that precedes by years and years any level of confidence that they can, with the needed degree of certainty, execute such an enormous undertaking.

It’s also a political gamble because of Chinese demographics. The youngest soldiers in China today are part of a generation in which most families don’t have any siblings. So, if that generation of soldiers were to take large numbers of casualties, that could literally end the family lines of thousands or more Chinese families. That is a bad thing in any culture, but I think it is something that has an especially profound meaning in Chinese culture. And this may also have something to do with the fact that there’s sentiment in the Chinese public that, while they want unification, they tend to have more temperate views about the ways in which China should pursue unification. I would also note that, and I mentioned this earlier, there’s a political cost to fighting against other Chinese people. It’s something that, from a political standpoint, would be another high bar for the government to clear to justify undertaking aggression against other Chinese people. I think I can leave it there, but would just add that the economic fallout that we talked about previously would be another major and probably greater source of deterrence or hesitation on the part of the P.R.C. leadership, because of their dependence on performance legitimacy. They would not take it lightly to impose greater economic hardship on themselves and on their own people for the sake of an elective military campaign, especially if they weren’t sure it was going to work.

TQ: Thank you, those are all fantastic points. Taking that realistic view of the factors at play here was a big part of why I enjoyed your article so much. Building on that, could you speak some as to how all these factors, while limiting the likelihood of a full-scale invasion across the Strait, raise the likelihood China may choose to undertake coercive strategies short of war? Please explain some of the actions short of war available to China and why they may be more appealing to Beijing.

JS: Well, it is really important to be clear about the fact that the P.R.C. does intend to continue pursuing cross-strait unification. So, if we think about the idea that a war of conquest would be the least attractive option, you have to work your way down from there to get to more and more appealing options. Short of war, you could have limited military intervention, and that would be something like a punitive operation which could be as blunt as launching missile strikes on Taiwan if the P.R.C. were sufficiently angered. Or, moved to take more meaningful action, they could launch missile strikes on the capitol with very high confidence that it would instill fear and perhaps force Taipei to decide if they wanted to basically shoot back and engage in a conventional tit-for-tat kind of escalation with China, which would probably not be an attractive option for the people in Taipei, or they could absorb the blow and be shown to be weak. That alone places Taipei’s leaders on the horns of a dilemma politically and militarily. So that seems like a much better option than a full-scale invasion where “it might work, it might not work,” but you would be virtually guaranteed to take heavy casualties. So, even that kind of punitive strike, which is an extreme example of aggression or escalation, is way less risky and way easier than would be this kind of go-for-broke invasion scenario. We’ve also seen examples recently where leadership is targeted in punitive strikes in other countries, not by the P.R.C., obviously, but suffice to say that it is now entirely plausible for governments with high-tech military capabilities to target the leadership structures of other countries with long-range missiles or cyber-attacks even. So, there are a variety of potentially lethal options that China could bring to bear on Taiwan that would not necessarily place its own forces at risk and would potentially place significant political pressure on leaders in Taipei

Moving down the list in terms of even easier escalation options than launching missile strikes or launching some kind of limited intervention or “special operation,” the government could institute a naval blockade. This is something that we’ve seen them practicing in terms of naval maneuvers and aerial maneuvers where they essentially have been demonstrating their ability to surround the island and cut it off from resupply and to cut the main island off from its outlying islands. Those exercises on their own, let alone a blockade actually implemented and enforced, serve as a psychological attack to remind Taipei that they don’t have the ability to fully control their access to other territories that are governed by the R.O.C. and they don’t have the ability to prevent China from encircling and cutting off access to the main island. This would also have an impact on Taiwan’s ability to trade. Taiwan would not be able to sustain energy production, for example, for more than a few weeks if it were cut off from outside supplies of oil and gas. So, the clock starts ticking pretty quickly if Beijing decides to implement that sort of thing, and it wouldn’t necessarily require any shooting, it would basically place the onus on Taipei and D.C. to decide whether or not to try to break such a blockade by force, or whether to comply with the quarantine. And the quarantine doesn’t have to look like a naval blockade per se. It could be presented as more of an administrative measure than that. It could be a new regulation by which the Chinese Coast Guard requires all goods being transferred to Taiwan to first pass through a port in mainland China for customs inspections or safety reasons. And so, countries that would wish to maintain positive relations with Beijing and continue their lucrative commerce in the Chinese market would just start to comply with that new regulation in order to avoid trouble and that kind of an administrative measure alone would have a significant enough impact on the Taiwan economy to make Taipei leaders think seriously about how to get out of that situation, again placing them on the horns of dilemma. “Do we escalate and engage in a fight that we don’t want and probably couldn’t prevail in? Or do we look weak and hope someone will come save us?”

TQ: It’s a scary thought, and unfortunately, I think that’s a lot more realistic than an invasion. That said, taken altogether, what does this mean for Taiwan and its partners? What should nations learn from these factors limiting China and how should they respond?

JS: Yeah, I mean that’s really the million-dollar question. And if I told you the answer, I might be out of a job. My humble opinion is that one of the things that has driven tension has been gestures of symbolic support for Taipei on the part of parties like the United States government or other governments. That’s something that Beijing pretty consistently and predictably responds to in ways that make Taiwan less secure. It seems to me that when we’ve seen the P.R.C. practicing these kinds of naval blockade style operations, it has tended to be in response to fairly symbolic political gestures by others, not by leaders in Taipei. So, I worry about that because I think that there are there are some in the United States who genuinely believe symbolic shows of political support are a meaningful source of deterrence, that the P.R.C. sees America’s commitment to Taiwan and is able to believe more firmly that the United States would therefore defend Taiwan if it were attacked. Now, I don’t personally think that Nancy Pelosi going to meet with the president of Taiwan means that the United States is more likely to defend Taiwan in the event that it’s attacked. I think that it’s intended to make people feel better, but what it does in a practical sense is it makes Beijing worry more and behave more aggressively in an effort to teach us a lesson about the consequences of what they regard as official interactions with the government in Taipei, which is something that the United States agreed not to have and which Beijing consistently attempts to prevent or deter. So, perhaps a more concise way of answering your question is to say that it’s important for us to remember that, even while we are thinking of our actions as contributing to deterring the P.R.C. from attacking Taiwan, Beijing is thinking about its actions as deterring the United States from violating the terms of the three joint communiques that Beijing and Washington agreed upon, and that includes having official relations with the government in Taipei. So, anytime the United States does something with its officials that relates directly to Taiwan’s officials, Beijing sees that as officials meeting officials doing official things—official relations, ipso facto. In their view that’s not allowed and they’re going to do something every time to remind us that we’re not supposed to do that. So, that’s a long-winded way of saying, item number one, don’t do things that predictably cause Beijing to dial up pressure on Taiwan, especially if there’s no material benefit to doing those things. If Taiwan doesn’t become materially more secure or more capable of defending itself as a result of those actions, if it’s just for political theater, so to speak, then I don’t think that the benefits outweigh the costs, especially for Taiwan.

Secondly, I think that there’s confusion or perhaps misunderstanding on the part of some in the U.S. defense community, and perhaps there’s a similar problem in Taiwan’s defense community, that leads some to argue that the United States should explicitly declare that Taiwan is a vital strategic interest of the United States. That’s why we would fight to defend Taiwan, because we insist that Taiwan must be left to its own devices, and that Beijing should not do anything to coerce Taiwan, regardless of what its goals might be.

Now, on the one hand, I concede that this approach might improve deterrence, at least in the near term. It might make it seem more credible to China that the United States views Taiwan as its own security interest. The problem with that way of thinking is that it frames Taiwan as something that the United States is committed to preventing the P.R.C. from ever touching, possessing, influencing, et cetera. In other words, it sets up a scenarios in which the United States and China are engaged in a zero-sum contest over Taiwan, and that the United States will not permit unification under any circumstances. That’s actually a radical departure from the United States’ actual purported position, which is that the U.S. would support any resolution to the cross-Strait dispute that was agreeable to both sides. So, that’s quite different. That’s saying it is up to the people of China—Mainland China and Taiwan—to figure out how to resolve their dispute, but that the United States has an interest in maintaining peace and stability across the Strait. So, no fighting, no coercion, otherwise, sort out whatever arrangement will work best for you. That’s the way that the United States has navigated this very difficult, very delicate issue to this point. But more recently, around the same time that the United States government started to talk openly about countering the Chinese Communist Party and making the government of the P.R.C. an object of contestation, a target to be removed, eliminated, undermined, et cetera, we also hear influential voices in the foreign policy community begin to talk about Taiwan as a vital strategic interest and as something that China must be prevented from acquiring. That subtle, simple change in rhetoric and framing is actually a breach of the accord between the U.S. and the P.R.C. that is represented in the three joint communiques about the United States not taking a position on the resolution of the cross-Strait dilemma. So, we have an interest in the political system and the way of life of the people of Taiwan, but it is not a declared U.S. policy objective to decide the outcome of Taiwan’s relations with the P.R.C. It’s simply the United States’ position that they should make sure whatever arrangement between themselves is mutually agreeable and they should not resume the Chinese Civil War. I think that well-intentioned people think that the issue can be resolved or improved by just clarifying that the United States won’t permit unification. But that’s actually not helpful because one of the conditions under which the P.R.C. has said that it would use force is if it cannot reasonably imagine unification by peaceful means as a workable approach, as delayed indefinitely. If we use our declared policies to take away the implicit option of peaceful unification, that removes the P.R.C.’s incentive or rational framework for pursuing peaceful unification and leaves them no other option but coercion and force.

TQ: Thank you, those are very salient and important points. The phrase “the road to hell is paved with good intentions” comes to mind. Moving now to your book China’s Use of Armed Coercion: To Win Without Fighting, it makes reference to “preventive deterrence activities” as a means of maintaining deterrence in peacetime. Please explain what this means in the context of China, both historically and in a modern context.

JS: The P.R.C. has, since its founding, pursued a strategy and doctrine of active defense, which essentially means waiting for the enemy to strike and then counter attacking. So, China’s strategic outlook is one of defending itself from a vulnerable and relatively weak position. The United States has been essentially the pacing threat, so to speak, for the P.R.C. since its founding. Obviously, that has a little bit to do with the fact that the United States was involved in supporting the other side in the Chinese Civil War and the United States and China came into active conflict in Korea. But, because China is focused on preparing for this possibility of fighting a stronger adversary from a position of relative weakness, it has focused on preparing asymmetric approaches to responding to outside aggression. And first and foremost, it is focused on deterring those kinds of military threats from emerging or trying to neutralize those threats, if necessary, as quickly as possible. That means using limited demonstrations of force in a predictable way in response to perceived violations of its red lines. That’s also one of the main reasons why I think we can expect the P.R.C. to consider pursuing unification through means other than a massive invasion; most of its approaches are focused on deterring Taiwan or the United States from doing things that the P.R.C. doesn’t want them to do. In a practical sense, this relates to what I was just talking about with regard to the military exercises demonstrating the P.R.C.’s ability to encircle Taiwan, for example. It is doing those kinds of exercises in the context of perceived encroachments on China’s core interests, perceived flouting of what the P.R.C. has said cannot be allowed, which in this example is official relations between D.C. and Taipei.

TQ: The strategy of “preventive deterrence activities” relies on limited cases of genuine combat to demonstrate one’s willingness to use its military capabilities when necessary. What does this limited genuine combat look like for China today?

JS: We can approach this a couple different ways, but let’s say there are the kinds of operations that China is currently engaged in, which are more demonstrations of force and demonstrations of capabilities, like the military exercises that we were just talking about, and the recent military parade which I will circle back to. And then, there are the kinds of examples of genuine combat, which, frankly, we haven’t seen China engage in since its punitive operations against India in 1962 or against Vietnam in 1979. Those were major combat operations, but even though what China’s doing now doesn’t really resemble what we would think of as modern combat, we have seen clashes of a sort that would have been easily recognizable as armed conflict in an earlier epoch of warfare, things like fighting with axes, rocks, and sticks, or ramming boats: these are all kind of earlier forms of military combat. China also uses less lethal or non-lethal tactics that we might associate with law enforcement activities, such as using water cannons or sirens or flares, bright lights, et cetera in an effort to both deter and also to compel adversaries to leave the area or stay away, as the case may be.

Now, going to the military parade factor, there’s this great quote from General John Hyten, who was Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; several years ago, as he was pushing to declassify some U.S. capabilities regarding anti-satellite weapons, he was quoted saying, “Deterrence does not happen in the classified world. Deterrence does not happen in the black; deterrence happens in the white.” What he was saying is that a critical element of deterrence is communication. You have to not only communicate to your opponent the things that you don’t want them to do, but you also have to convince them that you have the will and especially the ability to impose costs on them that would outweigh whatever benefits they might think they would get from doing what you told them not to do. It’s a convoluted way of saying that you have to persuade the folks that you’re trying to deter that you have the power to hurt them, and you have the power to hurt them so badly that they would rationally decide not to do what you told them not to do. So, a key aspect of deterrence is communication of your military capabilities, and that’s what things like military exercises can do. Military parades can contribute to deterrence in the sense that they can be used to reveal technologies, military capabilities, et cetera, that contribute to deterrence.

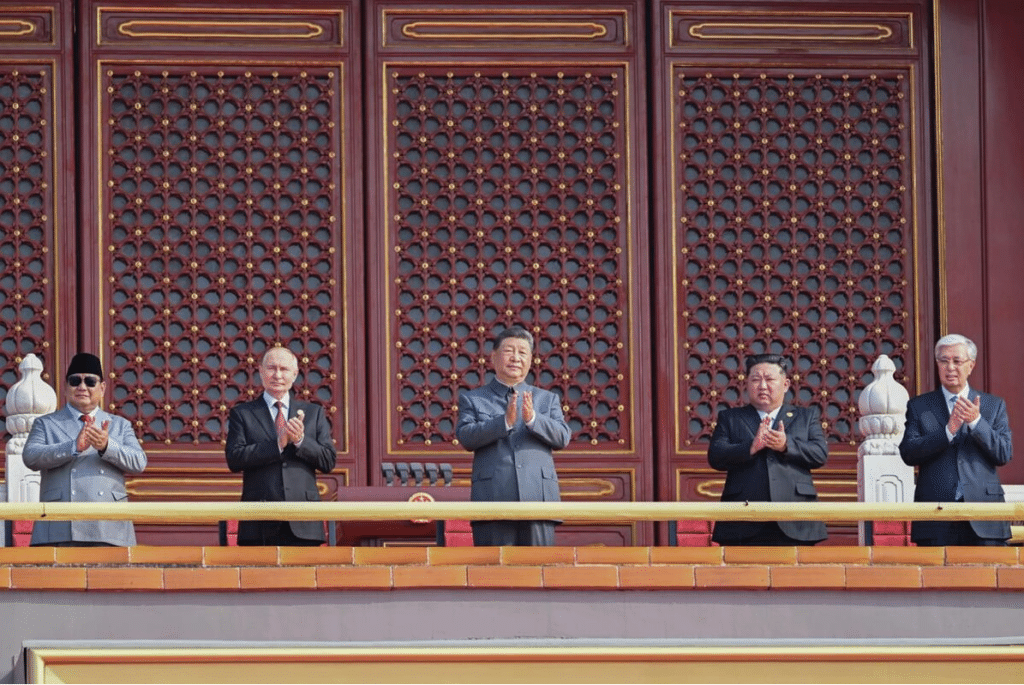

So, in China’s most recent military parade, we saw them trot out a variety of more modernized versions of missile systems that we’re already well aware of and which are already operational and also new kinds of systems that could give American military planners greater pause. These include long-range hypersonic missiles, new types of anti-ship missiles, three of which we think are hypersonic, as well as new variants of missile interceptors and anti-satellite missiles. These are all things that signal China’s growing military capabilities, including some capabilities that the U.S. can’t yet match, and capabilities like the anti-ship missile or the anti-satellite missiles that obviously imply strategic threats for the United States. And so that may cause the United States to be more concerned about the implications of intervening in a war across the Taiwan Strait. If it had to contemplate its capital ships being destroyed, it’s command, control, and communication systems, including satellite communications, being destroyed or disrupted as a result of that decision, that’s how deterrence works.

TQ: China’s coercion strategies include a unique aspect of “military-civil fusion,” seen particularly prominently in its activities in the South China Sea. Could you expand on how this increases the difficulty of responding to Chinese coercion, particularly for nations confronting this tactic with purely military force structures?

JS: It is the case that China leverages irregular units, paramilitary units to help form the tip of the spear for its contestation of territorial disputes, especially those that are less clearly under China’s effective control. So, they’ll use civilian fishing fleets as a means of probing and engaging in what’s sometimes called “maritime occupation,” where they just maintain a persistent presence in a locale. Scarborough Shoal is a very good example of this sort of tactic in practice, where, by virtue of just maintaining a civilian fishing fleet, they create a justification for increased Coast Guard escorts or patrols. Especially if their civilian fishing fleets are coming under harassment by local coast guards or maritime law enforcement agencies that are attempting to police their country’s exclusive economic zones. So, China might go into another country’s exclusive economic zone with its Coast Guard and protect Chinese ostensibly civilian fishing fleets from legitimate, lawful interception by the unwilling host country. China says that they are doing so based on their own assertion of exclusive economic rights or their own assertion of territorial water, depending on where we’re talking about. And that is a de facto means of establishing effective control because under international law, the country that is already in the place and is doing things in the place has that as evidence of their claim to the place. I’m not an international lawyer, but that is my understanding of one of the rationales for China’s increased patrols and increased economic activity in some of these areas. It is simply to say, at a minimum, you don’t have uncontested control of this area because we’re operating around here all the time, and our people are fishing in these waters just like they’re our waters. And perhaps a notch up from there is saying these are our uncontestable waters and you’re not even permitted to be here.

TQ: When it comes to coercion, what tactics lead to the greatest success for China? What coercive tactics have not worked? How can and should other countries react to these tactics?

JS: One of the things we did in the book was we conducted statistical analysis of a data set we created where we had attempted to catalog all of the instances of a Chinese military or paramilitary operation that had a clear coercive intent against an identifiable actor. We found that across the board, all else being equal, China tends to be more successful when it’s engaged in deterrence compared to when it’s trying to engage in compellence or responding to a violation of its previous deterrence demands. In other words, once deterrence fails, it has a hard time getting it back, and it has a hard time convincing others to change their behavior to either leave a place that they already are, or to change the way that they are operating. China, unsurprisingly, has had more success in coercing states that are militarily weaker relative to its efforts to coerce stronger states. I know that’s not a shocking finding, but it is also worth reflecting on the fact that that means weaker states are the ones that are likely in need of most outside support. It’s also the case that China has not been especially successful with some of the most frequently attempted kinds of operations, like when it establishes a new recurring patrol in a in a specific place. So, establishing new regular patrol routes does not improve the likelihood that it will achieve its coercive objectives, and in fact, it’s associated with failure. Also, engaging in the kinds of aggressive interceptions like ramming boats or flying too close to other planes, that’s also associated with failure.

I think one of the other things we can infer from this is that resistance works on some level. Basically, despite the fact that China has normalized military and law enforcement patrols, other countries have not given up on trying to exploit resources in their own exclusive economic zones. And, while the P.R.C. has made kind of incremental gains in terms of the kinds of facilities that it’s built on some of these outlying territories and features, that hasn’t prevented the United States from continuing to sail and operate through those waters or other countries, right? So China is threatening, but it is not typically deciding to escalate when those threats don’t succeed in deterring challenges. And then when it does escalate, it’s not escalating to armed conflict, it’s escalating to a kind of jockeying, bucking, and other kinds of intimidation tactics which may succeed in the specific instance but has not succeeded in the aggregate to fundamentally alter the behavior of others in the region. Also, nobody has recognized China’s territorial claims that they frequently insist upon. That’s maybe the clearest indication of something that they have not succeeded in compelling others to do—accepting, acknowledging, or formally recognizing China’s claims.

Author

-

Tyler Quillen is an intern for China Focus at The Carter Center and a graduate in International Security from the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Sam Nunn School of International Affairs.