Interview with Rana Mitter: How China’s WWII Memory Fuels New Nationalism

- Interviews

Alice Liu

Alice Liu- 11/17/2025

- 0

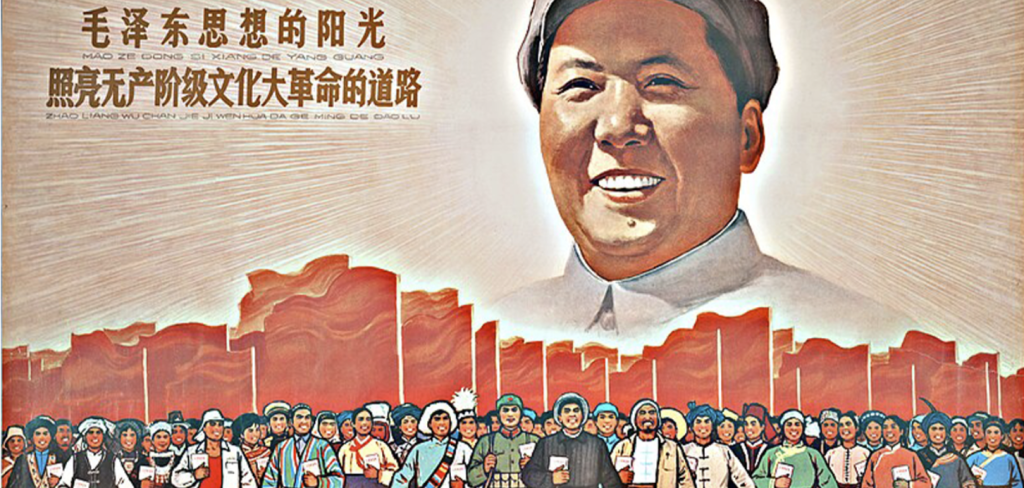

“Collective Memory – Zhongnanhai.” 2004-2008. Chen Shaoxiong. Source.

The Bretton Woods Conference initiated a decade that most nations would later call “the post-war era.” In the extended period of peace following the devastation of WWII, major European powers and the United States embraced rapid democratization and demilitarization. Most were able to reflect on the lessons of the war and incorporate wartime memory into their nation-building narratives, often highlighting the moral legitimacy gained from defeating the Nazis.

China stands in striking contrast to these countries, as it lacked a comparable post-war period; its War of Resistance against Japan dovetailed a Civil War. The ensuing Mao era allowed only limited reflection on the war, since doing so would require acknowledging the KMT’s contributions. It wasn’t until the 1980s, under Deng’s leadership, that there was active reinterpretation of the Great War to heal national divisions inflicted by the Cultural Revolution and to craft a new nationalism. Today, the Chinese Communist Party frequently deploys anti-Japanese sentiment as a potent vehicle for inciting patriotism.

Rana Mitter, in his 2020 book China’s Good War: How World War II is Shaping a New Nationalism, explored the Chinese historiography and cultural representation of this previously overlooked Second World War. Today, the Carter Center speaks with Professor Mitter to learn how collective memory of World War II conflicts with China’s past, and what the Chinese wartime history reveals about its present.

Previously a Professor of the History and Politics of Modern China at the University of Oxford, Rana Mitter is now the ST Lee Chair in US-Asia Relations at the Harvard Kennedy School. He holds expertise in contemporary Chinese politics. A prolific writer, Dr. Mitter regularly contributes to Foreign Affairs, Harvard Business Review, The Spectator, The Critic, and The Guardian.

Alice Liu: You published a book called China’s Good War: How World War II is Shaping a New Nationalism. What’s the book’s central message?

Rana Mitter: Readers familiar with American history might recognize a reference point in the book’s title—China’s Good War—that dates back to more than 40 years ago, when the great American oral historian Studs Terkel published a book called The Good War, detailing American service people’s experience of WWII. Terkel points out that while the war was fought seemingly in a virtuous cause—opposing Nazi power—in practice, for African Americans, their experience of fighting for the U.S. was often tainted by prejudice and racism.

He supported the war itself but was critical of how it was portrayed. I saw this as an ironic lens through which to view the collective memory of World War II in China, an important political issue. I spent a long time in lots of different places in China where people remember different aspects of World War II. It’s often forgotten that China was a significant wartime ally. Figures suggest that more than eight million Chinese died during the war. Terrible events such as the famine that hit central China meant that more than a hundred million Chinese may have become refugees within their own country.

My book focuses on how that war is remembered today. At its core, I argued that sustaining the memory of World War II as a virtuous, heroic event has been a prime task of the Chinese Communist Party. In other words, taking pride in China’s World War II sacrifices and experience has shaped China today.

AL: And what did you mean by “new nationalism”?

RM: Nationalism—an active political feeling about China’s place in the world—is not new at all in itself. But the fact that China’s nationalism includes its former political enemy makes it “new.” In commemorating World War II, the Party faces one political difficulty: the Chinese government in charge of China during WWII was not the Communists but the then Nationalist government under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek, a sworn enemy of the Communists. Consequently, it was politically awkward for today’s Communists to remember the Nationalists’ anti-Japanese war efforts—yet they managed to do so in some very creative ways.

AL: You positioned the 1980s as a turning point in the rewriting of China’s historical narrative. What are the domestic and international reasons for that?

RM: The 1980s are an absolutely pivotal turning point in terms of how World War II was remembered in China. In 1949, the Communists won their civil war against the Nationalists, founded the People’s Republic of China, and exiled the Nationalists to Taiwan. After the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s—a traumatic period when China seemed to be on the verge of implosion—China’s new Communist leaders who took over from Mao decided on two things.

The first outcome was the economic boom that went on to shape China’s development for decades afterward. The second thing the leaders decided on was that a new form of national ideology was needed. The Cultural Revolution wouldn’t do anymore; they were looking for alternative forms of nationalism that could be used to shape the next phase of Chinese development. In the 1980s, China not only embraced markets but also began reexamining its past more openly.

Deng Xiaoping’s “seek truth from facts” slogan encouraged China’s leading historians to reopen WWII archives. They decided that the way in which those formative and traumatic years were being taught in schools and understood in universities wasn’t good enough. Only a limited number of aspects—the Communist role—were discussed. The forbidden topics included Chiang Kai-shek and assistance given by the Americans or by the British. During the 1980s, such stories began to resurface, contributing to a much more balanced account of China’s WWII history.

Just to give one example, the Guomindang armies received little prominence in textbooks, movies, or museums. By the 1980s, scholars started to work on what they called the key battlefields of World War II, with the primary concentration on the Nationalist battlefields. That shift in the 1980s opened broader discussions on the meaning of World War II—its significance for the shaping of Chinese national history, identity, and character.

AL: What geopolitical factors drove this rewriting?

RM: Part of the motive for revising the wartime narrative and making it more inclusive of the old Nationalist Party was to reconcile with Taiwan. Bear in mind that then, as now, one of the key goals of the Beijing party-state was to unify Taiwan with the mainland. The two antagonistic parties nonetheless shared a belief that China should be unified. They only disagreed over who should lead the unification. In the 1980s, the CCP wished to foster warmth and understanding between the two sides by giving a more positive account of the Nationalist Party’s role.

Rewriting wartime history to create closeness with Taiwan had limited success as a tactic. The last time it was successful was probably about a decade ago, during the 70th anniversary of WWII, when the last KMT leader strongly advocated that it was important to acknowledge shared history across the Taiwan Strait. Now, 10 years later, the DPP leadership of Taiwan, which is much keener on an autonomous vision for Taiwan, does not accept that the mainland and Taiwan histories of World War II really have any very significant connection with each other.

It might have been easier to create that link 40 years ago, in the 1980s, when both countries were essentially under authoritarian regimes—because Taiwan had not yet democratized and the mainland PRC was liberalizing, yet still firmly under Communist rule. Perhaps at that point there was more room for dialogue between the two sides. I think it’s much harder now, with Taiwan being a multi-party liberal democracy—albeit sometimes quite a polarized one—and the mainland being much more authoritarian now under Xi Jinping than it was at the beginning of the eighties under Deng Xiaoping.

AL: Is World War II key to understanding contemporary Chinese nationalism?

RM: Yes, I think how World War II is understood is very significant for many aspects of contemporary Chinese nationalism. Let me offer a couple of reasons as to why that might be. The first one is something that’s perhaps often underestimated—that Chinese nationalism is not monolithic but influenced by regionalism. This is reflected in the differing memories that people have and pass down through generations and in the popular culture of wartime experience.

Shanghai and Beijing were occupied by the Japanese. Yan’an in Northwest China was under the rule of the growing Communist Party. Its Communist history has become part of a commercial and political phenomenon known as “red tourism” in China, in which people pay to go on luxurious tours to see, for example, where Chairman Mao and the Communist leaders lived in caves during World War II. That’s another aspect, and one that’s been quite well-publicized. But until relatively recently—two or three decades ago—there was much less emphasis on the huge parts of China, particularly the Southwest, which were under Nationalist rule. Those areas, under the control of a government heavily opposed to the Communist Party, were not permitted to talk about their wartime experience for many decades.

After the Communists came to power, they actively opposed promoting the history of Chongqing, the wartime KMT capital. Yet the official ban didn’t obliterate the trauma, the memories, the life experiences of people who lived through those years. Air raids by the Japanese frequently reduced large parts of the city of Chongqing to rubble. The immense trauma of millions of refugees fleeing inland fueled intense anti-Japanese sentiment, which the CCP harnessed in establishing the united front with the Nationalist Party.

But after the Civil War was over, that strongly pro-KMT, anti-Japanese war sentiment was largely dismissed. It wasn’t until the 1980s that that form of regionally inflected nationalism was allowed to be discussed again. Even now, it’s a sensitive issue. This is the PRC we’re talking about; it’s not a liberal democracy. You can’t simply speak out against the Party. But certain places like Huangshan, the old headquarters of Chiang Kai-shek out in the suburbs beyond Chongqing, have in recent years been available for tourists. These are tacit signs that elements of the Nationalist agenda persist in public memory.

WWII also contributes to understanding China’s growing international identity. This is linked to a very contemporary issue of China’s role in the United Nations. The way in which Xi Jinping, Wang Yi, and top leaders in China today talk about China’s role in the world involves frequent reminders that China was the first signatory to the United Nations Charter in San Francisco in 1945. This is crucial to China’s claim that the United States—not China—is the true global disruptor. Likewise, their claim is that China is the maintainer of global order.

And while that’s an internationalist enterprise in the sense of China taking its role—as a permanent five member of the UN Security Council—it’s also about restoring China’s sense of national pride. In other words, a country that for a hundred years was known in China as bai nian chi ru, the “hundred years of humiliation,” between the Opium Wars of the 1830s to World War II in the 1940s. In this vision, for a whole century China was on the defensive, being kicked around, invaded, and forced to obey global rules it had little part in shaping. 1945 is essentially a watershed moment when China eventually gets to join the top level of international politics.

An anomaly that isn’t really acknowledged in China today is that the government joining the UN was the Republic of China. It wasn’t until 1971 that the CCP took over the position. So, for about a quarter of a century, the government that held the China seat wasn’t the China of today. It’s very clear that today’s China, changing bits and pieces of the history to suit its own narrative, is very keen to stress a continuity between 1945—China’s World War II contribution and sacrifices leading to its place at the top table of diplomacy—all the way up to today.

AL: Do you see that narrative as sustainable? How does the Party balance this historical flexibility, recognizing the Nationalist Party’s contributions while not revealing the full extent of the KMT’s involvement?

RM: I think it’s manageable within China, because the capacity to control narratives is quite strong. In recent years, the Communist Party has preferred to leave out inconvenient facts. It’s more a history of omission than actively inventing things.

Let me give you an example, which shows how they handle the issue you’ve identified—a real challenge. Let’s take an event of global significance, which I mentioned briefly earlier: the signing of the United Nations Charter, marking the beginning of this immensely important global institution in San Francisco in April 1945. This event is commemorated in one of the major war museums in Beijing—lots of photographs, captions, and details. But it’s notable that when they show who was there—about a dozen Chinese delegates who went to sign—it turns out that figures who were in fact senior members of the Nationalist Party are simply referred to as “representatives of China.” That’s not entirely untrue; it’s accurate that they were representing China and that they were Chinese. But what’s intentionally left out is that, except for Dong Biwu, they were there as representatives of Chiang Kai-shek’s government.

Dong was a senior official of the Chinese Communist Party and the only representative of the CCP in San Francisco—partly because of internal disputes, since Chiang Kai-shek basically didn’t want to take any communists. By then, communists were still technically in the United Front, though it was a shaky alliance, and insisted that at least one communist be included. As a result, Dong Biwu got to go.

As a result, since he’s visible in the photographs, there’s a lot of emphasis in Beijing on Dong Biwu’s presence. Now, by no stretch of the imagination was he the senior or leading figure in that delegation. The heavy emphasis on his presence manages the historical narrative: it presents historical facts without stating anything false, while framing events to support the Party’s preferred message that, in some sense, the Communist Party was leading events during this period, even though the actual government of China then was their main rival, the Nationalist Party.

AL: Bridging this to the present day, how does China’s wartime memory or CCP’s writing of it function as a tool of diplomacy today?

RM: I would say that the CCP’s use of World War II history in international diplomacy is successful on some fronts, less so in others. The fronts where it’s successful are at home domestically and, to some extent, with its authoritarian friends—Russia, North Korea, and others. China has not been very successful in using WWII’s legacy to push ideas about China in the wider world, particularly the liberal world. The military parade held in September this year illustrates my point quite well.

A show of strength by today’s China, the parade was also a commemoration of the 80th anniversary of VJ Day, the victory over Japan. As such, the speech by Xi Jinping had to acknowledge WWII and used it to argue that that previous world had been one where fascist forces were rising, and that China had been central to pushing back against them. It fits into a wider patriotic narrative when the United States is currently pushing back against China on trade, technology, and other issues, and where the wider Chinese public feels uncertain about what is coming next from the U.S. This is a narrative that works for an audience at home in China, but not so much for a Western audience.

China’s declaration of its own central role at the UN is also not particularly well received in the Western world. Although it’s aimed at an international audience, that claim about the UN probably has more purchase either at home or, to some extent, in a limited way with non-democratic partners of China.

AL: The performative side of wartime memory is clear, but do you also think it also reflects genuine emotion?

RM: Yes. The performative element was particularly strong in the propaganda arm of the Party, but I think that the concentration on those wartime years absolutely encompasses genuine emotion, trauma, and desire to essentially go through many of the incidents that Chinese people experienced. For many people who suffered in wartime China, there were refugees who had to go into interior China—Chongqing and elsewhere—to escape the Japanese invasion.

And as I’ve mentioned before, those people were not in a position to tell their stories or grieve, even, very openly in Mao’s China because they’d been in “the wrong part of China”—the non-Communist parts of China. But because of the opening up that came in the eighties and nineties, the last phase when the country still had significant numbers of people alive who remembered those wartime years, public historians went to collect many of the stories of people who had been through that experience.

One of the things they recorded, along with many fascinating stories of what it was like to be a refugee escaping to the inland parts of China, away from the places that people had lived and known for most of their lives, was the feeling of relief. Among many of the people they interviewed, who were then probably in their seventies or eighties, a old person said to the interviewers, “I’m very glad you came. I’m not afraid of dying; I’ve had a long life. I was very afraid that I might die without my story being told.”

And so for those people, being able to relate wartime stories—not just about their trauma and experiences, but also how it made them feel as Chinese, being part of a resistance, feeling deep anger at the invasion by Japan, feeling a deep sense that they wanted to survive long enough to reclaim their country, huan wo he shan (“get back our rivers and mountains”), to use an old Chinese phrase—these sorts of ideas were very widespread. They were very genuinely felt. Yes, there’s an element of performance, then and now, on the grounds that people are required or expected to express such views; that, however, doesn’t make them inauthentic. In many cases, people were deeply angered by the unprovoked invasion of their country, and their reactions were entirely genuine.

AL: You once wrote that to discuss China’s political role entails distinguishing between “revisionist” and “revolutionary.” You seem to suggest that this is a false binary that inhibits our understanding of China’s role in the international arena. How is that so?

RM: Yes. One of the questions that gets asked quite frequently in international society is whether China is trying to break up the existing international order as it has existed since 1945, or is it seeking to revise it to its own purposes? And I think the answer is, broadly speaking, both. In an article called China in a World of Orders, the great scholar of international relations Alastair Iain Johnston provided a very insightful way of understanding this question by looking at eight or nine different orders in which China has a different role — sometimes upholding, sometimes revising, and occasionally overturning them.

My extrapolation is that, in terms of the overall structure of, say, the United Nations and international institutions, China is for the most part not trying to overthrow those; rather, it participates in them while becoming more powerful. There are also other areas in which China is very keen to overturn the existing broader interpretation. The UN Human Rights Council is a good example, where China has moved very far to argue that human rights should really revolve around issues of collective development and not individual civil liberties. In terms of revisionism, I would say that, broadly speaking, one of the areas where China has had the most impact is in areas already in flux— such as AI regulation.

AL: Going back to the book’s title, how do you see China’s Good War echoing the Western notion of the “Good War”? Is there also an ironic element to it, in your opinion?

RM: I would say that there is an irony, in that China’s war is portrayed as the foundation of its national identity, while many aspects of historical reality that underpin that view go against the worldview of the CCP. This includes the role of the Nationalist Party, international assistance to China, and a whole variety of emerging civil society groups such as women’s organizations. None of those are stories that are very amenable to the CCP — particularly its current interpretation, which is very much keen on stressing the role of the Communist Party above all.

I’d say that’s the central irony — that to make a story of a “good war,” you have to find ways to deal with the elements that add to the positive narrative of China’s achievements during the war. But the CCP also has to find ways to avoid praising its adversaries too much. That difficulty of dealing with deeply politically sensitive and problematic issues while crafting a good war makes it an ironic exercise.

AL: In the eighties, after Mao’s death, the CCP made the decision to reopen World War II archives. At the time, what were the benefits and risks that the Party perceived in reintroducing this historical period to its official story?

RM: The Party saw quite a few risks involved with entering the complexities of wartime history, and those risks remain palpable today. The major one was reviving popular sentiment about the war. While the Party was happy for there to be an increase in anti-Japanese sentiment to help in negotiations with Japan, they didn’t want it to grow uncontrollably to the extent of people stirring up riots. Beyond that, a second difficulty they foresaw is linked to the rise of social media in China. From the early 2000s to about 2012, when social media was relatively unregulated compared to now, people were talking more on social media about aspects of the war and its history in ways that the authorities found uncomfortable.

One example of that, again, I talk about a little bit in the book, is the so-called Guofen movement — meaning literally “fans of the Guomindang.” Obviously, becoming fans of the defeated KMT in China in real life would have been very difficult at any point, because you’d be arrested pretty quickly. But it was possible, at least for a while, for people to gather online through QQ or other social media and swap quite subversive ideas about what would have happened if Chiang had won the Civil War as well as World War II. And the opening up of a more positive narrative about the KMT allowed that danger to emerge again.

A more recent example from contemporary culture is the movie Babai (The Eight Hundred), which was about KMT soldiers fighting against the Japanese. It was made by a very mainstream director and film company in China and then banned on the eve of its release in 2019 because it was felt to be too favorable to the KMT, even though it had been made under mainland censorship. A year later, in 2020, it was released for the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II. But the fact that a film could make its way all the way through with actors, budgets, and distribution, and suddenly be banned because its worldview was considered too problematic, shows that even today opening up that space for discussion remains politically risky. The Party still doesn’t quite know how to manage it.

AL: In the conclusion, you wrote that nostalgia for the war echoes nostalgia for the Cultural Revolution — both are somewhat problematic yet powerful. What does this say about China’s emotional landscape of history?

RM: This statement has many implications. But the most important thing it reveals is that it is still very hard to find events from China’s relatively modern history that can bind people together in a feeling of relatively positive and uncomplicated pride. The Cultural Revolution, needless to say, cannot serve that function. And yet, quite surprisingly, there’s more nostalgia for the Cultural Revolution in China than people would expect. That nostalgia sits alongside millions of people who remember the period in utter horror. But there are others who regard it as a period when China had values, had purity. They’re not allowed to talk much about the Cultural Revolution officially, but again, they can talk on social media — and they do.

Cultural Revolution fans have a noisy online presence. But for most people, that is not at all a unifying narrative. Similarly, World War II is problematic for all the reasons we’ve discussed in this conversation. Its revival serves the CCP’s patriotic narrative, but only at the expense of opening up old wounds, particularly around China’s internal political division between nationalists and communists, something very hard to overcome even today. This is parallel to the situation in Vietnam, where the defeat of the South Vietnamese Anti-Communists in 1975 — relatively more recent — is still being processed as a trauma in that now-unified country.

It helps, to some extent, that in China the war was a generation earlier — in 1949 rather than 1975 — and therefore most of the people involved directly have clearly passed away. But collective memory is not always dependent upon having living witnesses still available. In this case, partly because the question of Taiwan continues to be of great contemporary significance, these traumatic issues make it impossible even now to find many aspects of Chinese modern history that can truly bind people together. And it’s one of the reasons that ancient Chinese civilization, I think, has been boosted so much. More mainland Chinese likely share a positive view of Confucius than agree on the meaning of World War II as a collective story. And that’s perhaps one of the reasons why Chinese ancient civilization has been so strongly emphasized.

Author

-

Alice Liu is an intern for China Focus at The Carter Center and studies History and Women’s Studies at Emory University.