Exclusive Interview | The Great Transformation: Westad Analyzes the Chaos and “Missed Opportunities” of the 1970s

- Interviews

Alice Liu

Alice Liu- 11/26/2025

- 0

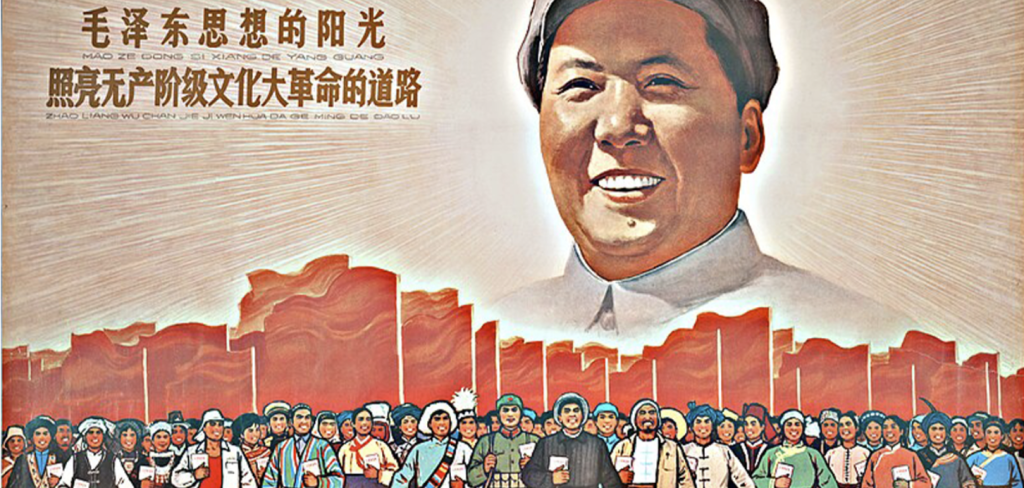

The Sunshine of Mao Zedong Thought Illuminates the Path of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Source

In the historical course of the People’s Republic, the 1970s remain a relatively little-known decade. The most chaotic peak of the Cultural Revolution had passed, yet the reforms of the 1980s had not yet begun. Caught between Marxist socialism and the nascent market reform that would define 21st century China was the obscure and pivotal 1970s.

In The Great Transformation: China’s Road from Revolution to Reform, co-authored by Odd Arne Westad and Chen Jian, the two leading scholars of Cold War history explore this crucial yet often overlooked decade. Drawing on interviews with numerous scholars, officials, journalists, businesspeople, and ordinary citizens, they reveal how the 1970s sowed the seeds of market transformation and political liberalization—developments that largely unfolded from the grassroots level.

This challenges the official narrative that attributes the country’s transformation solely to the top-down decisions of the 11th Central Committee’s Third Plenum. Instead, Westad and Chen show that it was ordinary Chinese people who stood at the forefront of change. They emphasize that China’s economic reform, as a historical outcome, was neither inevitable nor predetermined, and that the 1970s represented a moment when multiple pathways for the nation’s future were still possible.

Today, The Carter Center hosts a conversation with Professor Westad to better understand the China of the 1970s—a decade teeming with possibilities, power struggles, and both intellectual and economic activism.

Odd Arne Westad is the Elihu Professor of History at Yale University, specializing in Cold War and Chinese communist history. Chen Jian is the Hu Shih emeritus professor of History and China-US Relations at Cornell University and the Director of the NYU Shanghai-ECNU Center on Global History, Economy, and Culture. His interests include modern Chinese history, US-Sino relations, and Cold War international history.

Alice Liu: Professor, you’ve called the 1970s a turning point in Chinese history, a period that is often overlooked compared to the Cultural Revolution and the later development period. What’s the significance of the seventies, and what insights can we gain from studying this period more closely?

Odd Arne Westad: I saw the 1970s as, in many ways, the crucial decade for China in terms of becoming the China we know today. The changes from the Cultural Revolution and from earlier upheavals of the 20th century had been catastrophic for many people. It’s in the 1970s that this starts to turn around gradually, a process that makes it sensible to think of the 70s as a single decade, even though it’s an unusually long one. Some China historians now talk about the long 1970s—going from the late 1960s up to the mid-1980s.

And the reason for that is that all these processes of change took time. The peak of the Cultural Revolution was over by the late 1960s. Much of the fervor had gone out of that campaign, and you see grassroots attempts at changing China’s economy coming up already in the early 1970s. While Chairman Mao and his circle of radicals were still in power in Beijing, you can see that some of the grip, at least on how people think, was giving way already in the early 1970s. And after Mao’s death in 1976, this turned into a flood.

By the late 1970s, China was already a much more open society, a much more dynamic society in terms of the economy. And five years later, that process of reform toward markets, toward more openness, toward more engagement by people in how the country was run economically and politically—that was, in many ways, already entrenched. There have been setbacks since then—1989, the crushing of the student movement, and the turn to new forms of authoritarianism over the last decade also. But the basic shape of Chinese history had already changed by then in a very dramatic fashion. And that’s what happened in the 1970s.

AL: You wrote in the book that the Cultural Revolution was already pretty much over by ’68, but then the official narrative drags it on all the way up to ’76. Why do you think that was? And why do people tend to overlook or downplay the seventies?

OAW: Well, those two points that you just made are closely connected to each other. The leadership that took over through a military coup following Mao’s death in 1976 wanted to have this idea that they were the ones who instituted dramatic change in China. There were some elements of truth in that—I don’t think the change would’ve been as profound and as rapid if it weren’t for these changes at the center—but what they don’t want people to think about is that so much of this change came from below, came from people who took action themselves to free their families from poverty and the threat of hunger that had been there before by taking power into their own hands.

That’s something that authorities in China generally have not liked. They preferred the idea of top-down reform. 1978 is often seen as the key year here when Deng Xiaoping’s opening up was really solidified and at least some of the other reforms were enshrined in doctrine by the Communist Party. So I think that’s the reason for that. If you look at that earlier date, you also focus much more on change from below and change that came through society as a reaction against the Cultural Revolution—and not just from what happened at the top.

AL: You argue reform in China was not necessarily a top-down project but more so a bottom-up revolution. To give our readers a clearer picture, which social groups or regions were the first to push for change?

OAW: It happened more or less all over the country, but in relatively small and sometimes quite isolated settings. Though it’s important to underline that this couldn’t become a countrywide phenomenon until the political changes actually took place in Beijing. But by then, there was much that people who thought about reform could build on. Chen Jian and I, in this book, used data from various small enterprises or collective enterprises that had been set up mostly in coastal China—Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Fujian provinces—but also in the south in Guangdong, very often near the cities but not in the cities. Very often, small enterprises had been set up within people’s communes that were collectively run—not state-owned—but run by workers’ collectives or by the local authorities in these people’s communes. They began producing for general consumption over and above the plan. These places, within the strictly centralized planning system, would have had a set of targets they should fulfill.

And the way a planned economy works is that you work up to that target, and then you don’t do much more. What these people did was produce beyond their quotas, and therefore they ended up with surplus products that could be sold—totally illegally, of course. This was outside of what was accepted at that point, in the very early 1970s, and therefore they often didn’t receive money in return, but they received other products that they could then sell on. Particularly those who were close to the cities had many opportunities for doing that.

Gradually, this became monetized because if you were in Guangdong—particularly if you were in the Pearl River Delta—then you also had Hong Kong quite nearby. A couple of these collective enterprises were able to smuggle some of these products that they got in return downriver to Hong Kong well before the official reform started in Beijing. In one case that we unfortunately couldn’t cover in the book because of problems with secrecy and those kinds of issues in today’s China, one of these collective enterprises, by 1972 or early 1973, had even managed to open a Hong Kong bank account. Again, it was strictly illegal, but it gave them a leg up when the reform then got underway at the central level.

AL: That’s very interesting. And you suggested that China’s shift from Maoist socialism to early capitalism was neither inevitable nor predetermined. But rather, at every juncture, multiple pathways were possible. Can you highlight one or two key moments where a different decision might have dramatically changed China’s trajectory?

OAW: Chinese politics in the 1970s was pretty chaotic, and it was unclear who, in political terms, would come out on top in this process up to and right after the death of Mao Zedong. Mao had dominated Chinese politics and the Communist Party for so long that the idea of what was going to happen after he was gone was difficult to develop. There were different kinds of alternatives. The faction of the Cultural Revolution left, which Mao himself had supported but which, towards the end of his life, was led by his wife Jiang Qing and a group of people working closely with her, stood for a much more radical form of revolution. They wanted to move away from all the reform efforts we’ve discussed, especially those coming from below. They believed very, very firmly in the socialist principles of a centralized planned economy.

The military was probably the most powerful institution, and it was they, in the end, who clashed so much with the left that they carried out this coup just a month after Mao’s death and basically arrested the whole political left within the Communist Party. But they were also divided. Lots of people in the military had different kinds of ideas about China’s future and which direction China should move in. There were some people who were thinking about why China didn’t go back to the way it had been in the 1950s—recreate a model that was patterned on the Soviet Union that seemed to have worked relatively well back then and that Mao had broken away from.

He had broken with the Soviets both diplomatically and strategically. So there were loads of different alternatives that existed, and politics were pretty chaotic. It wasn’t guaranteed that the reformers—certainly not reformers around Deng Xiaoping—would come out on top. Frankly, Chen Jian and I believe that if it weren’t for the military coup, it would’ve taken much longer for some of these people to come into positions of power. Deng, after all, was someone who had been purged twice by Mao himself and was still living in fear of his life when Mao died. So this could easily have taken a different direction at the top.

AL: After Mao’s death, China could’ve easily returned to a central planned economy, but it didn’t. Why didn’t they go back to the Soviet template?

OAW: After the chaos of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, there were quite a few people within the Party who were thinking that back in the 1950s, when the Chinese Communists had just taken power and closely allied themselves with and patterned themselves on the Soviets, things were going pretty well. Mao would’ve disagreed—Mao’s view was that things were moving much too slowly and too carefully, that you had to have, as he called it, “a great leap into the future.” But after that had failed so spectacularly, it’s not difficult to understand that quite a few people were thinking, why don’t we go back to that?

The reason why that didn’t happen, in our opinion, was twofold. One was that there was so much enmity already at that point, politically, between the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party—including those who had pro-Maoist views—and the Soviets that it was very hard to go back there. But the other reason, and this is something that is a bit hard to understand, is that in the late 1970s, at least some of the people who were in charge of the Communist Party had concluded that it was not that form of economic development that seemed to be doing best on a global scale. It would be healthy and wise for China to learn from those countries that had experienced rapid economic growth—which the Soviet Union didn’t have—rather than just learning from the Soviet Union. So learning from Japan, from the United States, even from smaller countries in East Asia that seemed to be having an economic takeoff—that was key to why they didn’t go back to the Soviet version.

AL: How would you characterize the relationship between the Cultural Revolution and the reform era? Was the reform a complete rupture, or did the Cultural Revolution, as you suggest, in some way prepare the ground for it? That part struck me as particularly interesting.

OAW: That is an interesting point. It’s a tough point to come to terms with. The Cultural Revolution, the way Chen Jian and I see it is mainly a work of destruction. There wasn’t all that much positive in it, at least in its most active phase. I think the left, when you get into the 1970s, did have a political alternative to the reform era. But in the early phase, the Cultural Revolution was pretty destructive. What we find is that, in many ways, what the Cultural Revolution did was destroy many of the central points of old China. It took away many of those aspects of the development of China that were bound by Chinese traditions and Chinese ideas that came from earlier times.

Think of the relentless efforts to get children to criticize their parents and even their grandparents for not being politically awake enough and not understanding Maoism clearly enough. In a Chinese family setting, what that did was destroy respect for your elders. Family bonds are essential in Chinese culture. So when that period was over, you found a generation of young people who were pretty cynical about most things and pretty preoccupied with getting ahead themselves rather than relying on tradition, family, or even the Communist Party to get ahead.

That tendency toward self-interest was, ironically, well suited for the rise of markets and the start of capitalism in China. This was, of course, not what these people had in mind. This is not what the people who started the Cultural Revolution had in mind; they wanted the opposite. But history is sometimes like that—it moves in different directions from what had originally been intended.

AL: It helped prepare the mindset for reform. You noted how, even as China moved toward reform, it remained deeply state-centered in its narrative and practice. How do you see this tension between reform as a way to save the state and reform as a step toward genuine social liberalization?

OAW: I think it was both. From the side of the post-Mao leadership, when Deng Xiaoping and his people came back into power after having been on the outside for a while, they were shocked by how far backward the Chinese state had gone, and also by the kind of disregard the Communist Party was held in by most people because of what the communists had done to the country. So reform was an attempt at rescuing the Communist state without any doubt whatsoever.

They felt that they had to create rapid growth—if not, they said this internally—if not, the Communist Party would be done. So that is pretty clear. They were also willing to allow a degree of liberalization that went remarkably far and fast. I spent a lot of time in China during those years, and it was remarkable to see, almost from week to week, how people took new kinds of freedoms for themselves—not just economically, but also freedom of speech and organization, and in all cultural matters, gender-related matters, and all of these kinds of things.

And most of that came from below, and the government just felt that they didn’t have any choice but to accept it. Now, there were constant attempts at rolling some of these freedoms back—first in the mid-1980s, and then more catastrophically for the people involved in or after the 1989 democracy movement. But they were never able to do it fully because the Chinese people had had this taste of freedom, and also because they were afraid that if they started restricting matters too much in these areas, it would also influence the dynamics of economic reform. So that was the reason why they were also careful about rolling that back.

Now the situation is different. The argument is that China has already reached a really high level of development, and it’s easier for the Communist Party to centralize power and all activities—really more than was the case before. So you could say that reform—this is another of the strange, ironic outcomes of reform—is that, eventually, much later, it enabled the Party to take more total control than it was able to do in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution.

AL: What was the rationale behind their belief that rolling back some of those cultural liberalizations would make people resist economic reform?

OAW: Yes. That they wouldn’t be able to carry out economic reform to the extent that they hoped for. So the idea here was more that many of the people who were in the lead—younger people who were leading these reform efforts—were also people who valued some of their personal freedoms and their ability to move around, for instance, or to speak openly. And it was hard to crack down fully on those parts without the people they needed for the reform efforts becoming disenchanted or trying to move abroad or do very different kinds of things. So that’s outside of our time period.

But the best example of this is what happened in the wake of the 1989 crackdown. Even then, the leaders of the Party were very quick to assure people that this was a crackdown on what they saw as anti-Party, anti-state elements, and that they would try to move reform back to where it had been before 1989. There were people at that point—conservatives within the Party—who were trying to make use of this to undo most of the directions that had been taken since the late 1970s. And it was Deng himself and people working with him who said that that’s not the case. We are going to have a political dictatorship for sure, but with certain freedoms that are accepted within that framework.

AL: And building on this topic of reform, you wrote in your conclusion that the seventies were also a story of “missed opportunities,” especially in political reform. If you had to name one or two specific missed opportunities that most shaped China’s later trajectory, what would they be?

OAW: First and foremost, it had to do with political and social freedoms. I believe it would’ve been possible at that point to create a China that was much more pluralistic, where there were rights enshrined for people to speak much more openly and to organize much more openly. It would’ve been possible to do that without the leading role of the Communist Party necessarily suffering much from creating those kinds of freedoms. And there were people within the Party—quite a lot of people within the Party—who were thinking in those terms about Chinese development. The other thing that could have been done and should have been done, in my view, was to allow more room for people to set up their own organizations from below.

So even though the Communist Party probably wouldn’t have accepted political competition—a democratic political system—I think that was unrealistic at the time; it was not unrealistic to think that they would have allowed, at the local level, different kinds of instruments of governance, much more influenced by the local population on how the smaller parts of Chinese society were actually run. And over time, I believe what this would’ve led to is a much more open, much more pluralistic China. It could have eventually undermined the total power of the Communist Party, which would’ve been a good thing. I think that was one of the reasons why they were so careful about moving in that direction.

But it would have made for a better China. It would’ve made for a China in which people were freer and able to speak their minds. And those who are saying—quite a lot of people, including in the West today—who are saying, “well, this wouldn’t have worked because China would’ve been too chaotic to create the kind of sustained economic growth that it’s had,” that’s blatantly untrue. I mean, look at other countries in the region that have had strong economic growth as they became more democratic: Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, you name it. The idea that China should forever be condemned to dictatorship simply because it serves economic purposes—that argument we don’t buy. Chen Jian and I think that isn’t true.

Author

-

Alice Liu is an intern for China Focus at The Carter Center and studies History and Women’s Studies at Emory University.