Interview with Dr. Joel Wuthnow: The Risk of “Accidental War” in the Taiwan Strait and the Path to De-escalation

- Interviews

Tyler Quillen

Tyler Quillen- 12/04/2025

- 0

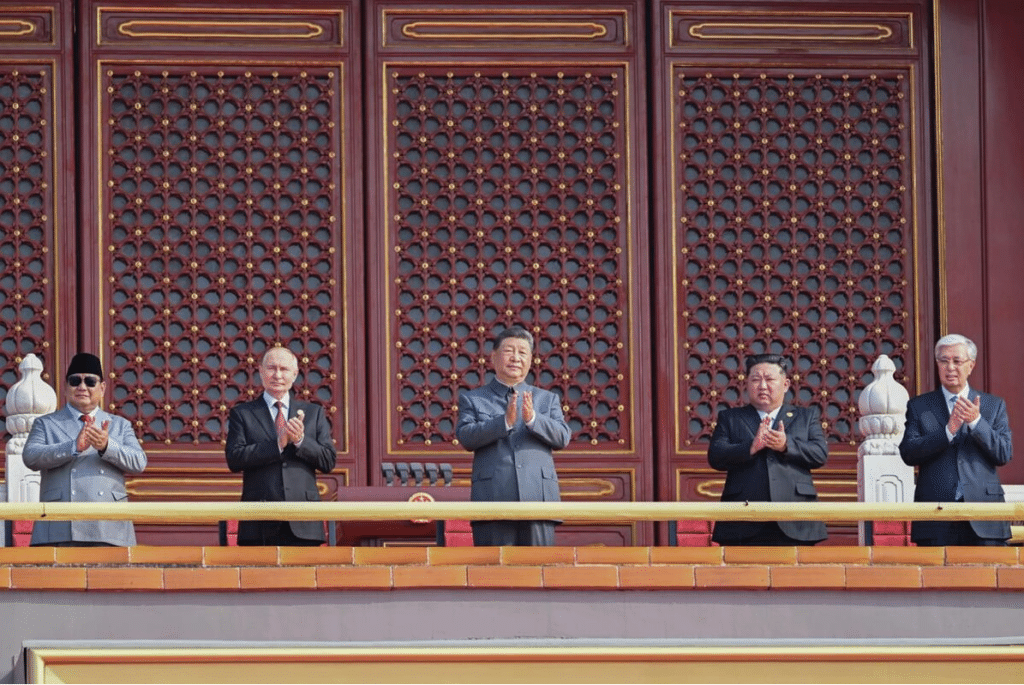

Soldiers of China’s People’s Liberation Army. 2011. Source.

Any who study international relations, security, and history will necessarily be familiar with the paradoxical cost-benefit structure of war: armed conflicts are both extremely inefficient and costly for all parties involved while simultaneously being regrettably common across history. One amongst the many explanations for war continuing to rear its ugly head despite its universally ruinous price is that conflict oftentimes arises without intention. As assuredly as the great powers at the turn of the 20th century did not seek to fall into a war that would kill millions and reshape the world in its entirety, so too do today’s world leaders not seek another world war that threatens society as we know it. Yet, just as tangled alliances, rampant militarism, and a catalyzing political assassination set a bloody chain reaction in motion more than a century ago, today again the stage is set for the possibility of a war no one wants to arrive all the same. In this context of a possible war of chance, rather than choice, between today’s great powers, it is more vital than ever to understand what may cause, and more pointedly prevent, of war of chance.

To better understand what dangers lie on the road ahead, as well as what may be done to disarm them, The Monitor spoke with Dr. Joel Wuthnow. Dr. Wuthnow is a senior research fellow in the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs within the Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University as well as an adjunct professor at Georgetown University. His research includes topics such as Chinese foreign and security policy, Chinese military affairs, U.S.-China relations, and strategic developments in East Asia. Moreover, he is the author of several published works, including China’s Quest for Military Supremacy, which he co-authored alongside Phillip C. Saunders, and his recent Foreign Affairs article The Greatest Danger in the Taiwan Strait. Tyler Quillen sat down with Dr. Wuthnow to discuss the risk of a war of chance in the Pacific, what makes this risk particularly acute in the Taiwan Strait, and what can be done to de-risk interactions between Washington, Beijing, and Taipei.

Tyler Quillen: To start out, please explain why you believe a war of chance in the Taiwan Strait could be more likely than one of choice or necessity.

Joel Wuthnow: I would argue that a war of chance is more likely because there are all sorts of confused and somewhat chaotic interactions happening in the Taiwan Strait. You have military and even civilian forces from both China and Taiwan operating in close proximity. That creates an environment where it’s possible for some kind of incident to occur that no one actually intended. By contrast, I don’t think a war of choice is as likely because it would require leaders in China to make a conscious decision to go to war. That would be extremely costly and risky for them, not only in military terms, but also economically and diplomatically. I don’t think they’ve made that decision, in part because of the damage a conflict could inflict on the regime. For those reasons, I think it’s more plausible that an accident could unfold that no one wanted but that could still escalate nonetheless.

TQ: What are the traits specific to cross-Strait tensions that make a war of chance particularly likely?

JW: I think the first factor is the huge amount of mutual distrust between China and Taiwan. Chinese leaders distrust the motives of Taiwan’s leadership, especially on questions of political autonomy and independence. On the other side, Taiwan’s leaders are skeptical of China’s claims that it does not seek war and prefers a peaceful resolution. That lack of trust makes it very difficult for either side to accurately assess the other’s intentions. For instance, if you’re in Taipei and you see a surge of People’s Liberation Army activity, you can’t be sure what the intent behind it is, and that naturally makes you nervous. In an environment like that, where neither side fully understands what the other is doing, the likelihood of an accidental incident increases.

The second factor is the sheer volume of activity in and around the Strait. Chinese aircraft and naval vessels are operating very close to Taiwan in large numbers as part of frequent military exercises. The more actors you have involved and the more crowded the operating environment becomes, the greater the chances that something will go wrong through miscalculation. Beyond that, there is also the presence of the United States in the background. One reason a seemingly small accident could escalate into a much larger conflict is the potential mobilization of U.S. forces. If Washington begins to mobilize, Chinese leaders might believe they are about to come under attack and decide they need to strike first. All of these dynamics occurring simultaneously raise the risk of an unwanted and escalating conflict.

TQ: Building off of that, how close has the region already come to a war of chance in previous incidents? What helped prevent these crises from elevating into full wars?

JW: There have been previous accidents, collisions, and near misses in the region, and these kinds of dangerous incidents occur every year. Some have involved U.S. and Chinese forces directly. The most noteworthy example was the 2001 EP-3 incident, which involved an actual collision between a Chinese fighter jet and a U.S. reconnaissance aircraft. History shows that leaders were ultimately able to resolve that crisis, but it took weeks of diplomacy and was a very difficult and dangerous moment for both sides.

There is no guarantee that future crises would be resolved as successfully, especially given today’s much higher and growing levels of distrust among all the parties involved. That’s what makes the situation particularly dangerous. It’s not only that these incidents continue to happen, but that the political climate has deteriorated to the point where it is much harder to identify and pursue an off-ramp when crises occur.

TQ: The U.S., the P.R.C., and Taiwan are all undoubtedly aware of the risk posed by mistakes or misinterpretations escalating into direct military confrontation. Why, then, do leaders continue to toe the edge of conflict?

JW: I think the reason China continues to push is because it gets a certain messaging or signaling value from what other parties would consider assertive or provocative military actions. What China gains from this is a display of force that underscores its frustration with developments in Taiwan or actions taken by the United States. Chinese leaders believe that a show of force is necessary to deter further moves in what they see as the wrong direction by their opponents, and that by taking calculated risks they can send a strong message.

But as I said, it’s a calculated risk, because they also understand that to send these messages effectively, you have to leave something to chance. You have to be willing to risk a disaster. And that is exactly what they’re doing. They are consciously creating a situation that could go badly. It probably won’t in most cases, but it could—and that possibility is what sends a strong signal, from China’s point of view, to both Taipei and Washington.

TQ: Thank you. What are the domestic political constraints for each of the three primary actors that heighten the risk of a war of chance and restrict policymakers’ ability to avoid one?

JW: The problem domestically is that nobody wants to look weak. From China’s point of view, if there is an accident or a collision, the last thing the leadership wants to do is take responsibility or say that it was actually their fault. In most incidents, the name of the game is blame. Each side blames the other for creating the conditions under which the accident happened. China’s leadership under Xi Jinping does not want to appear weak in the face of what they regard as Taiwan’s intransigence or foreign intervention.

Taiwan also faces domestic constraints, because its leaders cannot simply allow Chinese aircraft and ships to violate what they regard as their sovereignty. They need to look tough in order to protect their own territorial interests. And then, finally, the United States has its own domestic political calculus. It is difficult for any president, from either party, to look weak in the face of foreign aggression, especially when it involves threats to U.S. interests and regional peace and stability. The Taiwan Strait has been a longstanding U.S. interest since 1949, and especially since 1979 under the Taiwan Relations Act. No American leader wants to give the impression of giving the other side a pass.

All sides would face political costs if they backed down without being able to claim that they gained something in return. That is part of why, especially in today’s climate, finding off-ramps is particularly difficult and fraught with uncertainty for all sides.

TQ: To pull more on this thread, what can leaders in each nation do to mitigate these domestic pressures that restrict de-escalation?

JW: I think part of what leaders need to do is develop a shared understanding that accidents can happen, and that when certain episodes unfold, they are not necessarily the result of calculated choices by the other side. It would be beneficial for all three parties—China, Taiwan, and the United States—to find ways to discuss, perhaps through case studies or through games and simulations, how these problems could escalate. If that kind of dialogue is possible, then you can have conversations about the kinds of trade-offs or deals each side might be willing to make at different stages of a crisis in order to walk it back.

So, part of this is what happens before anything occurs, what we would call crisis prevention. The talks, agreements, and mechanisms that exist are meant to prevent crises from happening in the first place. But if a crisis were to occur, you would need very high-level diplomacy, because bureaucracies often find it difficult to communicate with each other. On the Chinese side in particular, their system really requires a green light from the top before officials can engage in crisis de-escalation. That means the relationship between the leaders—in this case, President Xi and President Trump—would be of paramount importance. They would need to be able to meet, talk, and find some way for both sides to save face in order to advance their shared interest of avoiding a larger conflict.

The additional wrinkle here is that there is no official relationship between China and Taiwan. My suggestion is that the two sides need a very candid but unofficial mechanism to share information and float proposals in the event of a crisis, but that is difficult for them to acknowledge publicly. They need some type of back-channel communication that would allow information about intentions—and about possible off-ramps—to be shared at critical moments.

TQ: That’s a fantastic answer, thank you. Moving on, your article cites scenarios of accidental military escalation being possible from any of the nations, but in very different ways. Please explain how they operate in and around the Taiwan Strait, why they do so, as well as what leads to their actions that risk escalation.

JW: From China’s point of view, they have several goals in the Taiwan Strait. First, as I mentioned earlier, they want to show strength when they feel they need to politically. Often this is to send a message when Taiwan’s leadership does something that Beijing cannot accept. But it’s not just about political signaling. They also want to provide training to the PLA. Operating in the Taiwan Strait and around Taiwan—in the air, at sea, and under the sea—is extremely useful training experience for the PLA, and that helps explain the parameters and characteristics of many of their exercises.

In addition, they gain value by probing Taiwan’s resolve and Taiwan’s defenses, and even by wearing those defenses down. Every time China sends a large number of aircraft and ships, that puts significant stress on Taiwan’s radars, its fighter aircraft, its surface ships, and other elements of its defensive infrastructure. So, China is trying to achieve all of these things at once: the political, the military, the signaling, and the operational.

From the U.S. point of view, we do not operate regularly in the Taiwan Strait. We conduct periodic transits, sometimes simply because it is the shortest route between Southeast and Northeast Asia. But at other times, we frame these transits as a kind of freedom of navigation operation to underscore that the Taiwan Strait is international waters, not internal waters of China. U.S. allies sometimes do the same. So that is the general character of our activity in the area—it is much less frequent than China’s.

Taiwan, for its part, conducts regular patrols within its 12- and 24-nautical-mile maritime zones, and it sends up aircraft to protect what it regards as its territorial airspace. But Taiwan’s activity is much more defensive in nature. They are not crossing the Taiwan Strait’s midline in the opposite direction or sending ships into China’s maritime exclusion zones.

What results is that each side has different motives and patterns of behavior, but these behaviors sometimes create overlapping forces operating in very close proximity—especially between China and Taiwan. That overlap is the focus of my argument, because it creates the greatest potential for incidents. There are fewer interactions between Chinese and U.S. forces, and when they do occur, it’s usually because the U.S. sends a ship or plane and China shadows it to send a message or track what we’re doing. But these encounters are less frequent. When you add it all up, the cumulative effect is a high level of China–Taiwan interaction that increases the prospects for dangerous incidents.

TQ: The current Trump administration has seen a lot of rapid changes in the U.S.’s relationship to plenty of foreign nations, China and Taiwan included. How has this affected American relations in the region and the possibility of accidental escalation? What impact has it had on communication with Beijing and Taipei?

JW: I think the most important recent development on that front is an improvement in U.S.–China relations, especially coming out of the APEC summit in South Korea, and also because of the leadership meeting between the defense chiefs that took place in Malaysia in late October. The leaders agreed that they want to try to de-conflict and de-escalate tensions, and that includes strengthening the military-to-military communications between the two sides. If we’re talking about preventing war or preventing a crisis, I think those signals from both capitals are encouraging. They seem to understand that frictions and tensions can sometimes spiral out of control, and they’re trying to get ahead of that by improving communication today so that we have relationships and mechanisms that could work tomorrow.

That is, from the standpoint of U.S. foreign policy, a very positive development. We’ve also continued to see a pattern of U.S.–Taiwan relations moving forward. Most recently, there was the announcement of another round of arms sales—totaling about a billion dollars—from the United States to Taiwan, the first such announcement under this administration. China’s reaction so far has been less assertive than it has been in the past, in part because the overall bilateral relationship between Washington and Beijing has begun to return to a more normal setting, including agreements on trade and other issues like fentanyl that fall outside the defense realm. Because of this, I think the relationship can tolerate some degree of U.S.–Taiwan interaction, and China’s leadership seems prepared to manage it in the context of a generally improving relationship.

So, I’m more optimistic today. But that said, U.S.–China interactions tend to come in cycles, and so do China–Taiwan interactions. Even if we’re at a more stable place right now, that doesn’t preclude the possibility of tensions resuming in the future. Having these relationships and discussions in place today is helpful in anticipating what could come next.

TQ: This very leader-forward form of communication and diplomacy that we’re seeing right now echoes to me things like President Nixon, President Carter, and President Reagan and that era of very leader-forward diplomacy that really opened the U.S. and China relationship. So, I’d like to hear your thoughts on how similar and or different today is compared to that.

JW: I think what we’re seeing today is a continuity in the importance of having a good relationship between the leader of China and the leader of the United States, whoever those individuals may be. That relationship really can unlock a lot of potential for the bureaucracies on both sides. As I mentioned with the defense establishments, in periods when leaders have not had a good relationship or have been arguing over a larger set of issues, it becomes much harder for defense officials to reach out and hold regular discussions. In fact, there have been times in U.S.–China relations when, after a political incident or crisis, regular exchanges have been cut off—by China more so than the United States. I think that’s detrimental.

My view is that those very important conversations should, as much as possible, be shielded from larger crises or day-to-day frictions in the relationship because of how important they are for preventing and managing crises. But sometimes the political instinct, especially for China, is to say, “We’re not going to talk to you for the next month or the next six months until you do something for us,” which usually means coming back to the negotiating table. From an international security perspective, that’s not very helpful, although I understand why they pursue that strategy.

To return to your main question, we do see the continuing importance of leader-level engagement, even though the nature of U.S.–China relations today is much more complicated than it was when President Carter or President Reagan were in office. There are so many more issues now. The trade volume is much larger, and the level of people-to-people interaction is much higher. So the relationship has become much more complex. The bureaucracies still play an important role, but if you don’t have a good relationship at the very apex of the system, managing that complexity becomes very difficult.

To sum it up, I was very pleased to see that we could continue to have not only a successful meeting, but also elements of progress on many of the thorny issues we’re facing, especially topics such as rare earths and the enforcement of fentanyl precursor inspections in China. Hopefully that will presage a better period in bilateral relations.

TQ: What safety measures currently exist to prevent miscalculations between these three nations? What more are needed to protect this fragile peace?

JW: All three sides have certain rules of behavior or rules of engagement that provide some level of insurance against accidents at sea or in the air. The PLA operates under specific rules of engagement, and Taiwan’s defenders likely have very strict rules as well. The same is true for the United States. So, the individual rules on each side are part of the equation. In addition to that, there are communications that occur between the leaders and the defense establishments in China and the United States. The quality of those has been variable. There have been times when those communications have worked well when there were concerns about a conflict and discussions helped ease tensions.

But there have also been times when the United States has complained that China does not answer the phone, because Beijing does not want to be seen as negotiating or yielding to what it views as foreign pressure. That is an unhelpful dynamic. Things are even more complex between China and Taiwan because, again, there are no official communication channels between them. They do have tactical-level communications—things like bridge-to-bridge interactions at sea—but at the leader level, it is much more circumscribed. As I said earlier, what they need is an effective set of back-channel conduits that are somewhat deniable, so that neither side feels it will look weak simply for talking to the other before an agreement has been reached.

That situation is somewhat reminiscent of U.S.–China relations before and during the Nixon era, when good unofficial ties were essential for preventing crises. Today looks similar in that sense. There is some connectivity, and leaders seem aware that crises can happen, but more communication between the capitals—and more established channels among all three sides—would be very useful, especially when difficult moments arise and it becomes hard to know what to do. Having that groundwork laid in advance is necessary today.

TQ: Thank you. This need for back-channel communications when mainline communications fail reminds me very much of the Cold War and the dynamic between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., where those sorts of back-channels were very useful during crises like the Cuban Missile Crisis. I’d love to hear your thoughts on how relevant a similarity that is and what we might be able to learn from back-channel communications during the Cold War, which succeeded in keeping the conflict largely cold.

JW: That’s a good question, and I think the Cuban Missile Crisis example is relevant. One of the ways we were able to resolve that crisis was through the use of a kind of middleman who passed messages back and forth between the two leaders. That was valuable because it meant you weren’t publicly negotiating with the other side. So, if a deal fell through, you weren’t accountable for it in the public eye. And if a deal required you to make painful choices, the visibility of your role in those choices could be minimized. In that sense, having back-channel communication is helpful.

This is especially true between China and Taiwan, because the CCP cannot be perceived as negotiating directly with a political party in Taiwan that it believes is pursuing independence. It’s easier when the KMT is in office because, in general, they have a better relationship with the CCP. But in periods like we’ve seen since 2016 under two DPP presidents, having some kind of very low-key interaction between China and Taiwan is useful for sharing concerns, demarcating red lines, and finding procedures through which they can coexist. They have done some of that, but I think they need to do even more today.

Between the United States and China, the situation is different. We’ve had formal diplomatic relations since 1979, and we’re not in a Cold War with China. There are many touchpoints between our governments—in the State Department, in the defense establishment, and at the leader level. Even so, in a true foreign policy crisis, you may want to keep your role low-key. Having a mediator or interlocutor who protects or buffers the leaders’ public image can be helpful until it becomes clear that the two sides have something meaningful to discuss.

Who that person might be, or under what circumstances such a channel would operate, is variable—and by design, we don’t typically know. But we have seen this administration use individuals outside the bureaucracy as back channels, for instance in the Middle East during the Gaza crisis. So, if a true U.S.–China military crisis unfolded, having an envoy of sorts speak in a very low-key manner could still be useful, despite the existence of stable formal relations between Washington and Beijing.

TQ: Continuing on, coordinating cooperation between these three nations with such tangled connections and interests is assuredly a herculean task. As such, what chance is there for a single actor, or two actors working together while the third does not, to seek risk reduction without the cooperation of all parties involved.

JW: I think that really mitigating the risk of a conflict borne from an accident would require participation from all three sides. From the U.S. perspective, the main concern is that China’s calculus is so different that its willingness to engage in real crisis prevention and management is either very low or contingent on having a healthy political relationship—something that may not always be present. Put a bit differently, the concern is that China sees more value in continuing a pattern of very intensive and provocative military moves around Taiwan, and that the value it derives from those actions outweighs the value it would get from coordinating on risk reduction.

If you asked people in Washington where the problem lies, I don’t think they would point to Taipei. Taiwan certainly wants to reduce its chances of getting into such a conflict to begin with. And I don’t think the issue is that the United States doesn’t care; in fact, the U.S. position—going back to President Carter—has been that our main interest is in maintaining a peaceful situation across the Strait. Anything that enhances that goal, including conversations with both China and Taiwan, is integral. The United States does not seek conflict. Some in China might believe that Washington is trying to use Taiwan to create a conflict, but I have never heard or seen anyone make that argument here. In reality, the priority is deterring and preventing conflict, not creating one.

So, I agree with the premise that we need buy-in from all three leaders. But the format of the discussion does not have to be trilateral, and I doubt it ever could be. The format needs to be multifaceted, meaning there are relationships between each pair of leaders individually, and there are also internal decisions within each government that collectively support a more advantageous solution for everyone. The imperative for leadership is to elevate the larger strategic goal above the political calculations that can sometimes make entering those discussions more difficult.

TQ: Thank you, that’s a great answer. It also leads very well into my next question. Given the difficulty of the three directly involved parties to self-manage tensions at times, what are the prospects for outside actors to help in preventing rampant escalation? What nations or non-governmental actors are best positioned to do so, and how might they accomplish this?

JW: I do think that other nations in Asia can voice support for positive U.S.–China relations and positive China–Taiwan interactions as well. That’s not very difficult for most countries to do, because if you look at their basic national interests, they are very much aligned with ours—namely, maintaining peace and stability. I don’t see any warmongering nations that want China and Taiwan to have a conflict. There would be broad support for efforts to prevent and manage crises in the region.

There is also an opportunity for NGOs, think tanks, and scholars to contribute. One contribution would be providing case studies to leaders, not only from past U.S.–China crises but also from other contexts, such as the Cuban Missile Crisis or other Cold War scares that are now distant memories. Historians can provide useful examples for leaders and policymakers to study so they understand that the risk is not negligible—that accidents and miscalculations have happened before.

Think tanks and NGOs can also promote productive conversations between China and Taiwan, or between the U.S. and China. That has been a role they’ve played in the past, bringing together scholars and people from the defense or national security establishments for what we call track two or track 1.5 discussions. This is especially valuable when official-level, or track one, conversations are stalled. These unofficial dialogues allow us to keep talking so that there is an agenda ready for when leader-level discussions resume.

We can also find ways to promote the flow of ideas among all three sides about how to manage crises, both in theory and in practice. Many of these efforts have been undertaken before, and I think it would behoove all three sides to continue them. None of this is to say that the three sides won’t continue acting on what they see as their national interests, and sometimes that may cut against the proposals of scholars. But as long as people committed to de-escalation and conflict prevention are offering ideas, suggestions, and opportunities to build connections and bridges, then I think the chances of leaders making better decisions improve.

TQ: You’ve yet again led very well into my next question, this one being the last. What should our readers take away from this precarious position and governments’ difficulty managing it at times? What role does civil society play in this balancing act and is there a central point or message that you want to leave with our readers?

JW: I think one of the things readers should understand is that there is a non-trivial prospect of a crisis in Asia. And it’s not necessarily because Xi Jinping wants to invade and govern Taiwan in the next year or two; that’s possible, but there are many problems and risks for him in doing so. What readers should take away is that the dangerous interactions we’re seeing in Asia could trigger a larger conflict that nobody wants and that would not be in the interest of any of the parties involved.

Leaders are, to some degree, influenced by public opinion. If the public voices support for de-escalation and for walking back tensions rather than urging leaders to be more assertive, then the public can play a role in balancing out some of the worst instincts leaders may face. This is especially true on the Chinese side because of the very high degree of nationalism wrapped up in this issue. If there are useful people-to-people discussions and engagements, and if a broader perspective is brought to bear on the question, leaders may be more likely to think twice about the value of ramping up tensions. They may conclude that there is actually a large constituency at home that does not want conflict.

So, I do think there is a role for civil society. Number one, it’s about awareness. And number two, it’s about public support—on all three sides—for prudent decision-making. This cannot be done in the United States alone. It is especially important on the Chinese side, where a strain of hypernationalism can push leaders in the opposite direction. Civil society can help encourage leaders to make more careful choices that favor peace and stability.

Author

-

Tyler Quillen is an intern for China Focus at The Carter Center and a graduate in International Security from the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Sam Nunn School of International Affairs.