Interview with Zhou Wenxing: Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations in the Next Few Years—Is War Inevitable?

- Interviews

Juan Zhang

Juan Zhang- 12/07/2025

- 0

During this in-depth interview, Dr. Zhou Wenxing, an Associate Professor at Nanjing University’s School of International Studies and Assistant Dean of Nanjing University’s Huazhi Institute for Global Governance, provided expert insights into critical issues: the likely path of cross-Taiwan Strait policy over the coming three to five years, the future prospects of cross-Strait unification, and the potential for armed conflict, and more.

You are about to publish an English-language book examining changes in Chinese mainland’s Taiwan policy. What are the two key takeaways you most hope readers will gain from this book?

Zhou Wenxing: My forthcoming English book is titled Explaining Taiwan’s Chinese Mainland Policy Change: A Punctuated Equilibrium Perspective (Chinese title: 《间断均衡理论视角下我国台湾地区的大陆政策变迁》).

As the title suggests, the book analyzes changes in Taiwan’s policy toward the Chinese mainland (known also as cross-Taiwan Strait policy). Any policy emerges and evolves through ongoing interactions and adjustments among different domestic and external actors. Taiwan’s authorities cannot formulate or adjust policies related to Taiwan’s status or cross-Strait relations without taking their interactions with the mainland into account. Naturally, the Chinese mainland’s Taiwan policy is a key counterpart in this process. Therefore, the book also devotes significant attention to the evolution of Beijing’s approach to Taiwan.

Broadly speaking, this is a work that blends theoretical inquiry with policy analysis, and different readers may derive very different insights from it. As a scholar—and also as a Chinese citizen—I offer the following two takeaways for readers’ consideration.

First, the Taiwan question is far more complex, sensitive, and dangerous than most people imagine. The issue is a legacy of China’s civil war, but because the United States has continuously intervened in cross-Strait affairs at varying levels to serve its narrow national interests, the problem has persisted until today. Interference in China’s internal affairs by the United States and other external powers inevitably provokes strong countermeasures from Beijing, which in turn heightens tensions in U.S.–China relations—as seen during the 1996 and 2022 Taiwan Strait crises. To remove this “flashpoint” in the bilateral relationship, Washington must cease interfering in the Taiwan issue. As the Chinese saying goes, “Whoever tied the bell must untie it.” The question of Taiwan must be resolved by Chinese people on both sides of the Strait. Any external interference only complicates the issue and increases its sensitivity and danger.

Second, the eventual outcome of the Taiwan issue is predetermined: Taiwan will return to the embrace of the motherland, and national reunification will be achieved. Although I emphasize the complexity and risks involved, the end state itself is clear. The very emergence of the Taiwan issue was a product of a weak and divided China. Seventy-five years later, China’s comprehensive national power—especially its military and economic strength—continues to rise, and the nation is moving rapidly toward great rejuvenation. The Taiwan question will inevitably be resolved. Cross-Strait unification is certain, and open-minded observers at home and abroad have long recognized this.

Some Chinese experts argue that maintaining the status quo is not Chinese mainland’s ultimate goal, and that unification is. Since Taiwan appears increasingly unwilling to accept peaceful unification, does this mean the mainland is destined for war over Taiwan?

Zhou Wenxing: For the Chinese mainland, maintaining the status quo is only a tactic or short-term objective. The long-term strategic goal is national reunification. As I noted above, the ultimate resolution of the Taiwan question lies in unification with the mainland. However, the path toward that outcome depends on assessments of numerous factors. Therefore, the specific manner of achieving unification—whether peaceful or non-peaceful—remains an open question. More precisely, it is a hypothetical question, difficult to answer and impossible to satisfy all parties.

But to address your question, I must first ask: Does Taiwan’s declining acceptance of peaceful unification necessarily correlate with the inevitability of war? We might need to examine the issue from another angle.

For instance, why do wars start, and which party triggers them? The Anti-Secession Law outlines several circumstances under which “the state shall employ non-peaceful means and other necessary measures to safeguard national sovereignty and territorial integrity.” You mentioned a shrinking possibility of peaceful unification. But has it shrunk to the extent described by the law—namely, a situation in which the possibility of peaceful reunification has been completely lost?

Another example: given the strong realist orientation of U.S. foreign policy, if China’s national strength—especially its military capabilities—were to surpass those of the United States and its key allies to such an extent that Washington is forced to withdraw entirely from cross-Strait affairs, would a Taiwan that previously resisted peaceful unification “change its mind”?

Furthermore, the answer depends on what you mean by “Taiwan.” Are you referring to the governing authorities, opposition parties, civic groups, or the general public? Although the Kuomintang (KMT, the Chinese Nationalist Party) has evolved into a party that emphasizes maintaining the cross-Strait status quo, it has not abandoned the pursuit of national unification. Public opinion is fluid, and ordinary Taiwanese people’s views on the island’s future are continually changing. In this regard, Beijing’s push in recent years for deepening cross-Strait economic and social integration is not only reasonable but necessary.

Looking ahead three to five years, what do you see as the three most likely scenarios for Taiwan’s cross-Strait policy, and what are the key triggers in each case?

Zhou Wenxing: In the book, I draw upon the strategic triangle model and two-level game theory to develop a framework for explaining and forecasting the formulation and evolution of Taiwan’s mainland policy. Put simply, the Taiwan authorities serve as an “intermediate agent” linking domestic and external actors. Domestically, they compete with the opposition for public opinion, forming one strategic triangle. Externally, they compete with the Chinese mainland for U.S. support, forming another triangle. Taiwan’s mainland policy is shaped jointly by these two triangles.

Based on this framework, I outline four possible scenarios in a scenario matrix: “Constrained Symbolism”: when the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is advantaged in domestic political competition and U.S.–China cooperation outweighs competition; “Assertive Autonomy”: when the DPP is advantaged domestically and U.S.–China competition outweighs cooperation; “Stable Engagement”: when the KMT is advantaged domestically and U.S.–China cooperation outweighs competition; “Fragile Balancing”: when the KMT is advantaged domestically and U.S.–China competition outweighs cooperation.

Applying this model, I assess the remaining three years of the Lai Ching-te administration’s mainland policy. Over the next three years, Taiwan’s approach is likely to oscillate between Constrained Symbolism and Assertive Autonomy.

For a DPP administration accustomed to framing cross-Strait issues through the lens of “resisting China and defending Taiwan,” emphasizing so-called “sovereignty” and “democracy,” along with symbolic provocations such as name rectification or “values-based diplomacy,” is a rational strategy amid the uncertainties of the Trump administration. However, if U.S.–China strategic competition escalates beyond the level President Trump still considers manageable, Taiwan may adopt a more adventurous mainland policy to enhance alignment with a Trump administration eager to “play the Taiwan card” against China. In that case, Taiwan’s mainland policy will become bolder and more autonomous.

The key trigger for both scenarios is the degree of U.S.–China competition—more specifically, President Trump’s stance on China policy and the Taiwan issue, and how Beijing responds. Of course, the framework also reminds us to pay attention to another important domestic actor: the opposition. The newly elected KMT chair, Cheng Li-wun, is rapidly contesting the DPP’s dominance over cross-Strait discourse, potentially shifting Taiwan’s domestic political balance and weakening the Lai authorities’ policymaking capacity. With no party holding a majority in the Legislative Yuan and a possible KMT–TPP (Taiwan People’s Party) alignment taking shape, additional constraints on the DPP are emerging.

Your research examines how U.S. think tanks engage with Taiwan-related issues. How do think tanks influence U.S. government or congressional legislation and policymaking on Taiwan? What are their main channels of operation?

Zhou Wenxing: The United States has the world’s largest and most influential think-tank community, and these institutions play a key role in shaping U.S. policy toward China, including Taiwan. They are therefore one of the primary objects of my research on the United States.

My article “The Intervention and Trend of American Conservative Think Tanks in U.S. Taiwan-related Policies—A Case Study during the Trump Presidency,” published in Research on Fujian–Taiwan Relations (No.1, 2021), analyzes three major conservative think tanks—the Heritage Foundation, the American Enterprise Institute, and the Hudson Institute. It examines their behavior and rationale during Trump’s first term in the Taiwan policy arena. I proposed a “six-stage model” of how conservative think tanks intervene in U.S. Taiwan-related policymaking: issue initiation, issue amplification, policy formation, policy release, policy promotion, and policy feedback. These six stages do not necessarily occur in strict sequence but collectively form an organic cycle through which think tanks shape U.S. policy on Taiwan.

For example, once a think-tank expert introduces a Taiwan-related concept or issue, their institution—and often others of similar orientation—will actively track and advance it. They may highlight it at public conferences, co-author policy reports with other think tanks or universities, and rely on amplification by media outlets, government officials, and policy organizations. This process strengthens the issue’s prominence. Think tanks then often “strike while the iron is hot” by inviting U.S. and Taiwanese officials to speak at events, providing congressional testimony, offering advice to executive-branch officials, visiting Taiwan, or communicating directly with policymakers in Washington and Taipei. Such activities help translate the issue into concrete policy initiatives.

Other types of think tanks—such as liberal institutions like Brookings Institution and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, or centrist ones like the Center for a New American Security and the Center for Strategic and International Studies—operate in broadly similar ways. All six stages play a role in their influence over both the executive branch and Congress.

You argue that the “internationalization” of the Taiwan issue has been a major factor behind the recent complexity in cross-Strait dynamics. Could you explain what “internationalization” entails and what drives it?

Zhou Wenxing: The “internationalization of the Taiwan question” refers to a growing trend in which the Taiwan question is increasingly framed and handled as an international matter—driven by the Taiwan authorities, especially the DPP, and by the United States.

In an article we published in Taiwan Research Journal (No. 2, 2025), we clarified the concept by identifying two components: Taiwan’s “international presence” and the “international resolution” of the Taiwan issue.

“International presence” refers to efforts by the Taiwan authorities to highlight their so-called “international visibility,” expanding their “international participation” and “international space” with the tacit or explicit support of the United States and its allies.

The “international resolution” of the Taiwan issue refers to Western countries—led by the United States—attempting to inject “international factors” into the resolution of the Taiwan question through political statements, legislation, and military cooperation. Their goal is to impose costs on China and obstruct Beijing’s peaceful resolution of the issue and eventual national reunification.

Although internationalization is not new, it became a focal point because the Biden administration played the “Taiwan card” with unprecedented intensity. However, since President Trump began his second term in January 2025, the internationalization trend has shown what I call a “deceleration.” We discuss this in detail in an article published in the latest issue of Research on Fujian–Taiwan Relations (No. 3, 2025).

Our analysis shows that the Biden administration pursued internationalization through five main avenues: constructing discursive “legitimacy,” legislative support, alliance-network reinforcement, shoring up Taiwan’s diplomatic ties, and expanding issue areas. As we have observed over the past ten months, the Trump administration has relaxed or reversed internationalization efforts in multiple areas, especially within U.S. alliance system.

Based on our research, U.S. motivations for internationalizing the Taiwan question are multi-layered: short-term goals include alliance management and aligning U.S. policy preferences with the DPP’s “pro-U.S., resistance to China” agenda; longer-term goals serve broader U.S. strategic competition with China and the preservation of American hegemony.

The mainstream view in the United States is that supporting Taiwan is not interference in China’s internal affairs but a defense of a small, friendly democratic partner. This differs sharply from mainstream views in China. How would you persuade the American public that China’s position also has reasonable foundations?

Zhou Wenxing: Before answering, we must define what you mean by “mainstream view in the United States.” Does it refer to the larger population, or to the louder and more influential minority? These are very different things. Consider a loosely analogous situation: a political leader who wins an election does not necessarily represent the majority of society. Many voters may have stayed home, while a minority of active voters delivered a narrow plurality—but the winner may still claim to have “mainstream support.” The reality may be quite different.

Based on my close observation of U.S. Taiwan-related debates in recent years, I do not believe there is a true “mainstream” position. If anything, the “mainstream” consists of the small group that controls policy resources at a given moment, not the broader American public.

Some may cite surveys—such as those by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs—to argue that rising support for military aid or defending Taiwan represents mainstream American opinion. But among these respondents, how many have ever visited Taiwan or understand basic facts about cross-Strait relations? Street interviews in the United States have shown that many Americans cannot even locate Taiwan on a map. Even many U.S. lawmakers who advocate strong intervention in cross-Strait affairs (with the exception of those on the foreign affairs committees) know little about Taiwan—let alone the general public.

It is true that many Americans consider themselves the “chosen people” of a “city upon a hill” and tend to support the “underdog.” In U.S. Taiwan policy, this manifests as sustained arms sales and political support for Taiwan in order to help it withstand pressure from the Chinese mainland. As Beijing’s pressure has intensified, U.S. support has also increased.

This behavior appears grounded in moral considerations. But scholars of U.S.–China relations know that morality is merely a pretext. From Henry Kissinger’s secret visit, to Richard Nixon’s trip to China, to Jimmy Carter’s normalization of diplomatic relations, successive U.S. administrations affirmed that Taiwan is part of China, that there is only one China, and that Taiwan does not and cannot possess the attributes of a sovereign state.

However, after the sudden end of the Cold War, U.S. policy cognition became muddled and regressed. In the early 21st century, as China’s power grew, various dubious arguments reemerged in the U.S. strategic community—some conservative think tanks promoted the “undetermined status of Taiwan,” some advocated “U.S. defense of Taiwan,” and Congress even entertained proposals for “restoring diplomatic relations” with Taipei. Viewed over a long historical arc, a strategic through-line becomes clear: Taiwan is a key instrument for the United States to contain China, and moral rhetoric merely serves as a convenient curtain over this strategic purpose.

In today’s context of deep structural tensions in U.S.–China relations, American politicians are doubling down on the “Taiwan card.” Ordinary Americans—many of whom cannot locate Taiwan on a map—are influenced by repeated political and media narratives portraying “democratic Taiwan” confronting “authoritarian China.” Under these conditions, persuading the U.S. public to appreciate the logic behind China’s position is extraordinarily difficult.

As the saying goes, “Friendship between nations lies in friendship between peoples.” Encouraging more Americans—especially students and young people—to visit, study in, or travel to China may help them better understand China and, in that process, gain exposure to the Taiwan issue. This may be one of the few viable ways to foster more nuanced public understanding.

What practical, operational communication channels or crisis-management mechanisms can China and the United States use to reduce the risk of conflict over Taiwan during periods of heightened tension?

Zhou Wenxing: To my knowledge, China and the United States once maintained multi-tiered communication channels and crisis-management mechanisms. But this changed fundamentally after the Donald Trump administration came to power in 2017 and launched a strategy of competition with China. The Joe Biden administration did not restore the mechanisms damaged under the Republicans. Instead, due to challenges such as COVID-19 and the escalation of the Ukraine crisis, it made little progress in managing U.S.–China relations. Biden also became the first U.S. president since normalization in 1979 not to visit China during his term.

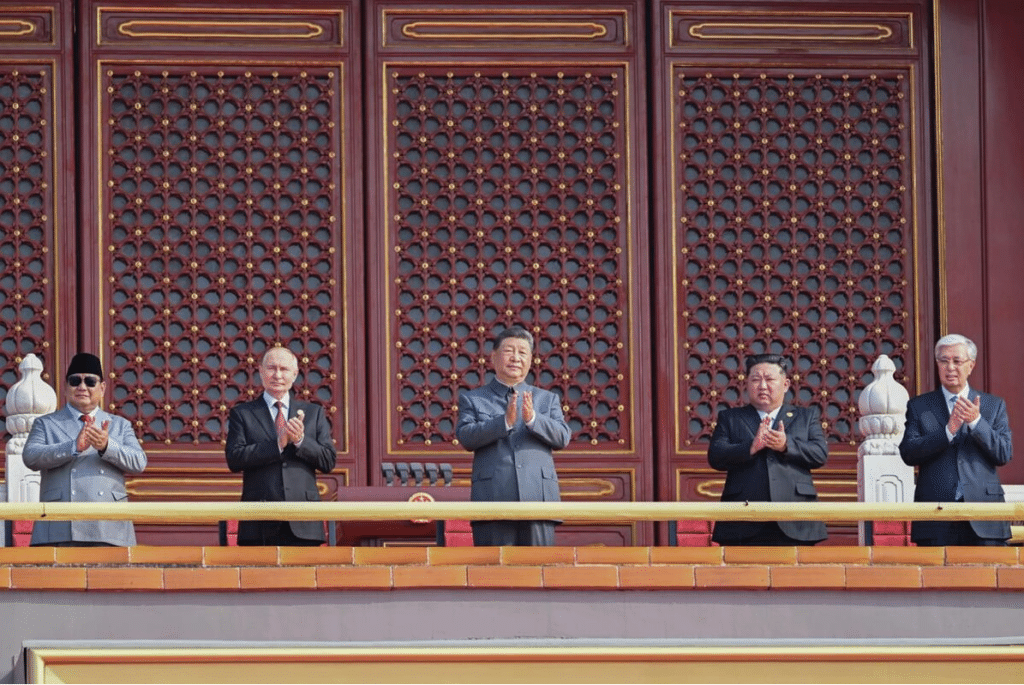

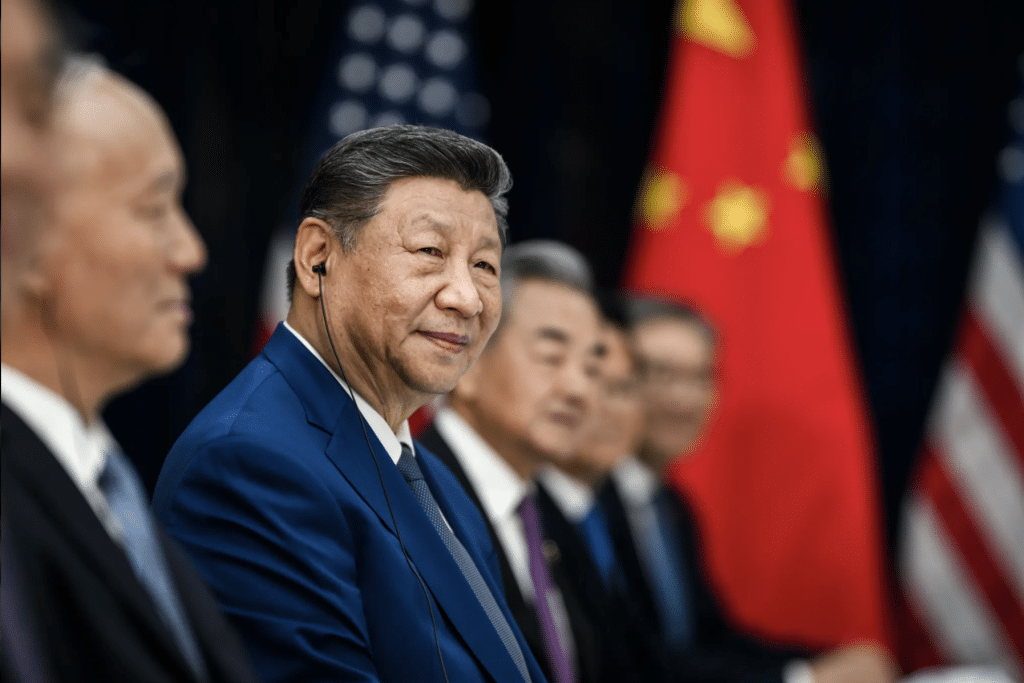

In recent years, high-level strategic communication—especially direct exchanges between the two heads of state—has become increasingly important. This year’s October 30 meeting between President Xi Jinping and President Trump in Busan, South Korea, and their November 24 phone call, both placed significant—indeed central—focus on the Taiwan issue. These interactions demonstrate the critical role of strategic leadership by the two presidents during periods of uncertainty in U.S.–China relations. They help reduce the risk of conflict in the Taiwan Strait and prevent a head-on collision between the two countries.

Ideally, as U.S.–China engagement becomes more frequent and the relationship stabilizes, both sides should restore or establish multi-level, practical, and operational communication channels and crisis-management mechanisms. That is the hallmark of major-power responsibility and strategic wisdom. But on the Taiwan question, the United States must recognize the objective reality that both sides of the Strait belong to one China and that reunification is inevitable. Otherwise, before reaching strategic stability, the two countries will continue to cycle through crises—undermining trust, complicating global problem-solving, and ultimately harming U.S. national interests in the long run.

Author

-

Juan Zhang is a senior writer for the U.S.-China Perception Monitor and managing editor for 中美印象 (The Monitor’s Chinese language publication).