As global climate cooperation discussions evolve across high-level meetings such as the UN General Assembly (UNGA), New York Climate Week, and COP30, Climind founder and UN Young Leader for the SDGs Hanyuan (Karen) Wang dives into the past, present, and future of AI climate solutions in this interview.

Hanyuan (Karen) Wang serves as the CEO and founder of Climind, a platform that delivers actionable climate data infrastructure through AI technologies to facilitate mitigation and adaptation solutions. She is the first Chinese woman to be selected as a Young Leader for the SDGs recognized by the United Nations.

Additionally, she serves on the board of NGOs globally, including being the youngest Board of Directors for the Foundation for the Museum of the United Nations – UN Live. She is also on the Advisory Committee of AI Hong Kong on the Energy and Utility sector.

Karen was a research assistant at Imperial College London’s Centre for Climate Finance and Investment (CCFI), where her work centered on voluntary carbon markets, climate risks, and nature-based solutions with a particular focus on the Asian Market. She was named to Forbes’ 30 Under 30. In addition to her climate-focused pursuits, Karen has gained valuable experience in the data sector through her work with Merrill Lynch and Microsoft. She went to Hong Kong Baptist University, Imperial College London, and is a Schwarzman Scholar from Tsinghua University.

With her Bai ethnic background, Karen also dedicates her time to preserving the disappearing Bai dialect in China.

Wei Wei Chen (WWC): Thank you so much for taking the time to interview. Could you start by telling us a little bit more about yourself, Climind, and the work that you do at the intersection of AI and climate change?

Hanyuan Karen Wang (HKW): Thank you. Climind started with the ambition to build practical AI tools for sustainability. I’m now taking this interview from Hong Kong where the headquarters is for my team of around 10. We build all sorts of applications on top of the large language model for knowledge workers focusing on sustainability across the financial sector like insurance asset, asset management, hedge fund, and beyond. We also do projects with multinational companies, think tanks, philanthropies, and universities. The core value here is I believe the future of AI tools should be more problem-solving focused, and you need the specialized tool rather than a general one for everything.

I started my career in AI and data. This is my second startup project, but the first one I started on my own. I was born and raised in mainland China, and got my education in Hong Kong, UK, and US. I started in statistics and computer science. My first time working in climate was when I was working at Microsoft. Microsoft had AI For Good Lab and I remember working on a remote sensing project. This opened a new door for me into climate change solutions. That’s why I moved to the UK to study at the Imperial College of London. During my first master degree, I ended up working at the university at its Centre for Climate Finance and Investment (CCFI). And that working experience motivated me to do this work at Climind now because it’s so slow. People will spend years doing research, sitting in the office writing reports. Meanwhile, climate change is a quite urgent issue. So I wanted to do something—perhaps in a very naive way—to increase efficiency for people like myself. After CCFI, I got a chance to come back to China for my second masters degree as a Schwarzman Scholar, which aligned with my goal because I think there’s no better place to build things with this kind of scale.

WWC: You described the AI tools you’re building for sustainability as practical. What sort of technology counts as “practical” and is at the cutting-edge of this industry right now?

HKW: I don’t think we need introduction courses for large language models anymore. ChatGPT is occupying the headlines everywhere, but “useful” and “practical” AI for sustainability means a tool specific for knowledge workers. I think the trend of AI tools will be more vertical focused because it will use up all the data material information on websites to train the foundation model. What’s missing here is it’s still not enough to solve the professional areas problem either for security or accuracy concerns. So you see that the companies are building their own in-house tools and AI teams. I also noticed that there’s a trend of companies moving to a more sustainable business model.

Just to give you a sense how slow this sector has been. It takes an average of four to five years to generate one report and that report kind of guides how policy is made at different levels. It’s a global coordination challenge. More than that, in the past, we have very limited access to technologies to gain direct data about climate risks, but it’s no longer the case anymore.

Additionally, I think innovation happens around the role of a human being. So in the future, we have to ask: what kind of jobs do we need and how do we adapt to them? This is happening at the same time as us having the new tools and thinking about what we are trying to do to catch the time window and then trying to move the whole sector. Whether you are doing compliance for recycling in Europe, carbon trading, or climate insurance elsewhere, there is no specialized tool in this market right now. So far, I think we are one of the first.

In general, more opportunities are created. I think the speed of AI development is definitely beyond what we could imagine. How do we maximize the efficiency of resources, including energy? AI is a big consumer of energy. That’s why you see a lot of the companies are investing in data centers right now.

WWC: You mentioned Climind is filling the gaps as one of the first robust AI tools for the knowledge workers within the climate space. Your influence is very vast; you recently participated in the United Nations University’s Global AI Networkand you’re also backed and featured by Tsinghua x-lab. What are the advantages you face in terms of innovation, in terms of advancing your mission as a startup?

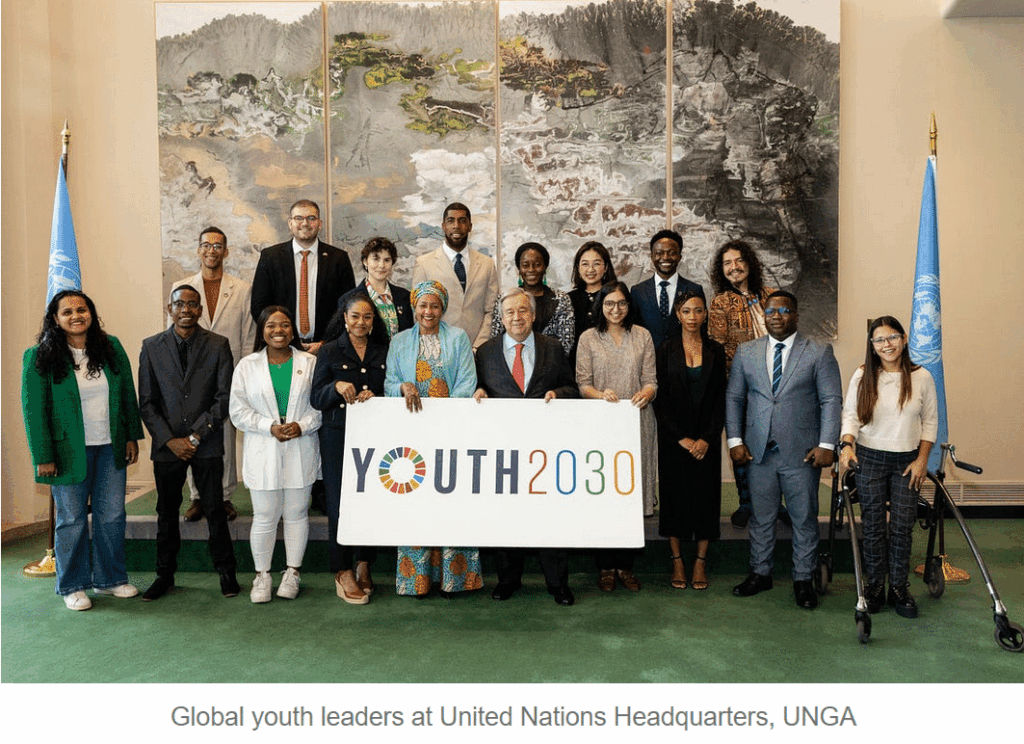

HKW: I was the first Chinese woman selected as a Young Leader for the SDGs at the UN (17 in total globally). It brought me the opportunity to speak at very important conferences, including UNGA, MiSK Forum, FII and more. And then, you mentioned United Nations University’s Global AI Network. The UNU has a center in Macau, so we actually got two papers accepted recently for the upcoming conference about AI for battery environmental compliance and climate. We also built a robust knowledge graph and model for lithium battery environmental compliance that integrates sophisticated algorithms and large-scale data processing, outperforming all existing general models in the market. The UNU also has a committee bringing together people from industry and academia to join the conversation.

Regarding x-lab at Tsinghua University, I see it as an extension of my Schwarzman Scholars experience—a dynamic startup incubator that provided tremendous support in terms of mentorship, funding, publicity, and market access. More importantly, there’s truly no better place than Tsinghua to find exceptional talent. It was also through this program that I met my first angel investor, Ms. Guo Meiling, through x-lab (美灵未来科创家项目).

I believe the private sector is ultimately the most efficient driver of problem-solving. It has the flexibility, speed, and incentive structures needed to turn ideas into scalable solutions. That said, NGOs play an irreplaceable role in areas the private sector often cannot, especially when it comes to building trust, mobilizing communities, and addressing issues where profit incentives don’t apply.

In our case, we even work with nonprofit clients who use our AI tools to support their workshops and knowledge-sharing. From what I’ve observed, also serving on the board of the Museum for United Nations – UN Live, the private sector is increasingly taking the lead—and that’s actually a positive sign of convergence between innovation and social impact.

The second point is that today, you can build a highly scalable startup with a very small team. We’re a very tiny team because you don’t need that many people and other work coding; more than 50% of the coding is actually done by AI right now in our team already. So I think the format of a startup—how it works today—is also a natural advantage. The competition of scaling has evolved.

And third one is that we’re now sitting in Asia, but if you look at the client portfolio, we are literally exchanging emails and talking to teams globally. I’m still working and it’s almost 9:30 p.m. right now, but it’s daily for me. I think it’s quite good for us because generally the working culture in Asia, I think it’s more used to these longer hours. We also have access to a strong talent pool surrounding us.

WWC: And the disadvantages?

HKW: The first challenge—and something I think about every day—is how to move fast and solve complex problems in an increasingly dynamic global landscape. The AI race today is probably the fastest we’ve ever seen, and to stay ahead, we need to go both deep and comprehensive at the same time. For us, that means being technically excellent, earning client trust, and maintaining professionalism while scaling—which is always a challenge for a young company.

The second challenge is how to sustain growth—and do it fast. We started from environmental compliance, but we’re now expanding toward a much larger market. One of our recent projects, still confidential, reflects that shift. I can’t share full details yet, but what I can say is that the future of global business will have to be truly ESG—and it goes far beyond just the “E.” AI will be essential in making that transformation possible.

Going back to the advantages, government support has certainly helped. Our initial bootstrap funding actually came from a Hong Kong Science and Technology Park (HKSTP) grant, which is quite unique to this ecosystem. While the U.S. has programs like the IRA for green initiatives, Hong Kong’s setup offers strong early-stage support.

That said, government grants also come with their challenges—mainly the slow administrative process. Startups can’t afford to rely solely on them; they’re great for getting from zero to one, but you have to survive long enough to receive the funding.

Beyond the financial side, grants and social engagements contribute valuable visibility and social capital, which I see as another form of capital for startups. Ultimately, though, what really matters is building a product that creates genuine impact—that’s what people will remember, not just the titles or affiliations.

WWC: You said you are the first Chinese woman selected as a Young Leader for the SDGs recognized by the United Nations. Tell us more about your experience advocating for climate change solutions among young leaders and across the board as you’re working with advantages and disadvantages in this space.

HKW: The United Nations is a large intergovernmental platform built around advocacy—it brings together countries and people of all ages. But historically, youth voices have been underrepresented, which is why the Office of the UN Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth created programs by the youth, for the youth.

The SDG Young Leaders Program, which I’m part of, is one of its flagship initiatives. Every two years, only 17 individuals are selected globally, with no guarantee of regional representation. I’m honored to be the second Chinese Young Leader and the first Chinese woman ever chosen. The selection process is incredibly competitive—this year alone, there were over 33,000 applicants worldwide.

My first year was intense. I found myself speaking at conferences across Asia, GCC, the U.S., and Europe, representing the UN and the global youth community. My very first appearance was at the United Nations General Assembly, where I presented in front of five former presidents and prime ministers. It was overwhelming but also transformative—suddenly, I wasn’t just speaking for myself but for a generation.

By my second year, I started to reflect more deeply on what this platform meant. This isn’t the fastest way to build an AI company—constant travel and public engagements take tremendous energy. But I’ve learned that time is the only real currency. Big success often comes down to timing, luck, and the readiness to take opportunities when they appear.

WWC: What are you excited about for the future? Also, with all of these climate conferences that are happening now, what do you think is important for people to keep in mind within this sector?

HKW: What I’m excited about for the future is that we’re entering a moment where AI and climate are no longer separate conversations—they’re becoming deeply intertwined. I just came back from the Future Investment Initiative (FII), and with COP30 around the corner, it’s clear that there’s no shortage of dialogue around climate change or accessibility. But what I’m increasingly hearing—and what also shapes our own strategy—are three key shifts.

First, the race in AI is ultimately a race for energy. The capacity to compute is defined by the capacity to power, and both are unevenly distributed. Just as access to data and models defines who leads in AI, access to clean and affordable energy will define who leads in sustainability.

Second, the investment momentum is enormous—and still accelerating. A lot of capital expenditures are flowing into building data centers and energy infrastructure to support AI. But we still know far more about the supply side of energy than the demand side. I think the next wave of innovation will come from understanding how energy is actually used—not just how it’s produced—and that’s an area I’m personally very interested in exploring further.

Third, I’m deeply encouraged by the rise of youth participation—not only in advocacy but also in solutions. This generation is entering the workforce with the most powerful tools ever created. The question now is how to use them well—with responsibility, with ethics, and with purpose.

As someone who benefited enormously from higher education, I also believe education is the real foundation of climate accessibility. One of our recent projects, in collaboration with UNESCO, looks at how many “climate schools” are being established globally and what they actually teach. We’ll publish the findings soon, and I hope it will serve as a blueprint for places still lacking access to environmental and technological education.

So while the challenges are real, I remain optimistic in front of uncertainty—because we’re not just discussing the future anymore; we’re actively building it, with knowledge, collaboration, and the right kind of intelligence—both human and artificial.